(Press-News.org)

VIDEO:

The movie shows the injector firing into open air without a skin or gel target. The jet, which is approximately the diameter of a human hair, seems dispersed but a...

Click here for more information.

WASHINGTON, Sept. 13—From annual flu shots to childhood immunizations, needle injections are among the least popular staples of medical care. Though various techniques have been developed in hopes of taking the "ouch" out of injections, hypodermic needles are still the first choice for ease-of-use, precision, and control.

A new laser-based system, however, that blasts microscopic jets of drugs into the skin could soon make getting a shot as painless as being hit with a puff of air.

The system uses an erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet, or Er:YAG, laser to propel a tiny, precise stream of medicine with just the right amount of force. This type of laser is commonly used by dermatologists, "particularly for facial esthetic treatments," says Jack Yoh, professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at Seoul National University in South Korea, who developed the device along with his graduate students. Yoh and his team describe the injector in a paper published today in the Optical Society's (OSA) journal Optics Letters.

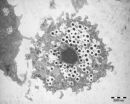

The laser is combined with a small adaptor that contains the drug to be delivered, in liquid form, plus a chamber containing water that acts as a "driving" fluid. A flexible membrane separates these two liquids. Each laser pulse, which lasts just 250 millionths of a second, generates a vapor bubble inside the driving fluid. The pressure of that bubble puts elastic strain on the membrane, causing the drug to be forcefully ejected from a miniature nozzle in a narrow jet a mere 150 millionths of a meter (micrometers) in diameter, just a little larger than the width of a human hair.

"The impacting jet pressure is higher than the skin tensile strength and thus causes the jet to smoothly penetrate into the targeted depth underneath the skin, without any splashback of the drug," Yoh says. Tests on guinea pig skin show that the drug-laden jet can penetrate up to several millimeters beneath the skin surface, with no damage to the tissue. Because of the narrowness and quickness of the jet, it should cause little or no pain, Yoh says. "However, our aim is the epidermal layer," which is located closer to the skin surface, at a depth of only about 500 micrometers. This region of the skin has no nerve endings, so the method "will be completely pain-free," he says.

In previous studies, the researchers used a laser wavelength that was not well absorbed by the water of the driving liquid, causing the formation of tiny shock waves that dissipated energy and hampered the formation of the vapor bubble. In the new work, Yoh and colleagues use a laser with a wavelength of 2,940 nanometers, which is readily absorbed by water. This allows the formation of a larger and more stable vapor bubble "which then induces higher pressure on the membrane," he explains. "This is ideal for creating the jet and significantly improves skin penetration."

Although other research groups have developed similar injectors, "they are mechanically driven," using piston-like devices to force drugs into the skin, which gives less control over the jet strength and the drug dosage, Yoh says. "The laser-driven microjet injector can precisely control dose and the depth of drug penetration underneath the skin. Control via laser power is the major advancement over other devices, I believe."

Yoh is now working with a company to produce low-cost replaceable injectors for clinical use. "In the immediate future, this technology could be most easily adopted to situations where small doses of drugs are injected at multiple sites," he says. "Further work would be necessary to adopt it for scenarios like mass vaccine injections for children."

INFORMATION:

Paper: "Er:YAG laser pulse for small-dose splashback-free microjet transdermal drug delivery," Optics Letters, Vol. 37, Issue 18, pp. 3894-3896 (2012). http://www.opticsinfobase.org/ol/abstract.cfm?uri=ol-37-18-3894

EDITOR'S NOTE: High-resolution images and a video clip are available to members of the media upon request. Contact Angela Stark, astark@osa.org.

About Optics Letters

Published by the Optical Society (OSA), Optics Letters offers rapid dissemination of new results in all areas of optics with short, original, peer-reviewed communications. Optics Letters covers the latest research in optical science, including optical measurements, optical components and devices, atmospheric optics, biomedical optics, Fourier optics, integrated optics, optical processing, optoelectronics, lasers, nonlinear optics, optical storage and holography, optical coherence, polarization, quantum electronics, ultrafast optical phenomena, photonic crystals, and fiber optics. This journal, edited by Alan E. Willner of the University of Southern California and published twice each month, is where readers look for the latest discoveries in optics. Visit www.OpticsInfoBase.org/OL.

About OSA

Uniting more than 180,000 professionals from 175 countries, the Optical Society (OSA) brings together the global optics community through its programs and initiatives. Since 1916 OSA has worked to advance the common interests of the field, providing educational resources to the scientists, engineers and business leaders who work in the field by promoting the science of light and the advanced technologies made possible by optics and photonics. OSA publications, events, technical groups and programs foster optics knowledge and scientific collaboration among all those with an interest in optics and photonics. For more information, visit www.osa.org.

Laser-powered 'needle' promises pain-free injections

Optical technology gives a sci-fi twist to traditional medicine

2012-09-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

IU chemist develops new synthesis of most useful, yet expensive, antimalarial drug

2012-09-13

BLOOMINGTON, Ind. -- In 2010 malaria caused an estimated 665,000 deaths, mostly among African children. Now, chemists at Indiana University have developed a new synthesis for the world's most useful antimalarial drug, artemisinin, giving hope that fully synthetic artemisinin might help reduce the cost of the live-saving drug in the future.

Effective deployment of ACT, or artemisinin-based combination therapy, has been slow due to high production costs of artemisinin. The World Health Organization has set a target "per gram" cost for artemisinin of 25 cents or less, but ...

Study of giant viruses shakes up tree of life

2012-09-13

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — A new study of giant viruses supports the idea that viruses are ancient living organisms and not inanimate molecular remnants run amok, as some scientists have argued. The study reshapes the universal family tree, adding a fourth major branch to the three that most scientists agree represent the fundamental domains of life.

The new findings appear in the journal BMC Evolutionary Biology.

The researchers used a relatively new method to peer into the distant past. Rather than comparing genetic sequences, which are unstable and change rapidly over time, ...

Scientists use sound waves to levitate liquids, improve pharmaceuticals

2012-09-13

It's not a magic trick and it's not sleight of hand – scientists really are using levitation to improve the drug development process, eventually yielding more effective pharmaceuticals with fewer side effects.

Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory have discovered a way to use sound waves to levitate individual droplets of solutions containing different pharmaceuticals. While the connection between levitation and drug development may not be immediately apparent, a special relationship emerges at the molecular level.

At the molecular ...

Increased dietary fructose linked to elevated uric acid levels and lower liver energy stores

2012-09-13

Obese patients with type 2 diabetes who consume higher amounts of fructose display reduced levels of liver adenosine triphosphate (ATP)—a compound involved in the energy transfer between cells. The findings, published in the September issue of Hepatology, a journal of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, indicate that elevated uric acid levels (hyperuricemia) are associated with more severe hepatic ATP depletion in response to fructose intake.

This exploratory study, funded in part by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and ...

Poorest miss out on benefits, experience more material hardship, since 1996 welfare reform

2012-09-13

Although the federal government's 1996 reform of welfare brought some improvements for the nation's poor, it also may have made extremely poor Americans worse off, new research shows.

The reforms radically changed cash assistance—what most Americans think of as 'welfare'— by imposing lifetime limits on the receipt of aid and requiring recipients to work. About the same time, major social policy reforms during the 1990s raised the benefits of work for low-income families.

In the wake of these changes, millions of previous welfare recipients, largely single mothers, ...

Mutation breaks HIV's resistance to drugs

2012-09-13

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) can contain dozens of different mutations, called polymorphisms. In a recent study an international team of researchers, including MU scientists, found that one of those mutations, called 172K, made certain forms of the virus more susceptible to treatment. Soon, doctors will be able to use this knowledge to improve the drug regiment they prescribe to HIV-infected individuals.

"The 172K polymorphism makes certain forms of HIV less resistant to drugs," said Stefan Sarafianos, corresponding author of the study and researcher at MU's ...

UMD study shows exercise may protect against future emotional stress

2012-09-13

Moderate exercise may help people cope with anxiety and stress for an extended period of time post-workout, according to a study by kinesiology researchers in the University of Maryland School of Public Health published in the journal Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise.

"While it is well-known that exercise improves mood, among other benefits, not as much is known about the potency of exercise's impact on emotional state and whether these positive effects endure when we're faced with everyday stressors once we leave the gym," explains J. Carson Smith, assistant ...

Snakes minus birds equals more spiders for Guam

2012-09-13

HOUSTON -- (Sept. 13, 2012) -- In one of the first studies to examine how the loss of forest birds is effecting Guam's island ecosystem, biologists from Rice University, the University of Washington and the University of Guam found that the Pacific island's jungles have as many as 40 times more spiders than are found on nearby islands like Saipan.

"You can't walk through the jungles on Guam without a stick in your hand to knock down the spiderwebs," said Haldre Rogers, a Huxley Fellow in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at Rice and the lead author of a new study this ...

Under-twisted DNA origami delivers cancer drugs to tumors

2012-09-13

Scientists at Karolinska Institutet in Sweden describe in a new study how so-called DNA origami can enhance the effect of certain cytostatics used in the treatment of cancer. With the aid of modern nanotechnology, scientists can target drugs direct to the tumour while leaving surrounding healthy tissue untouched.

The drug doxorubicin has long been used as a cytostatic (toxin) for cancer treatment but can cause serious adverse reactions such as myocardial disease and severe nausea. Because of this, scientists have been trying to find a means of delivering the drug to the ...

Daily disinfection of isolation rooms reduces contamination of healthcare workers' hands

2012-09-13

CHICAGO (September 13, 2012) – New research demonstrates that daily cleaning of high-touch surfaces in isolation rooms of patients with Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) or methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) significantly reduces the rate of the pathogens on the hands of healthcare personnel. The findings underscore the importance of environmental cleaning for reducing the spread of difficult to treat infections. The study is published in the October issue of Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, the journal of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Putting some ‘muscle’ into material design

House fires release harmful compounds into the air

Novel structural insights into Phytophthora effectors challenge long-held assumptions in plant pathology

Q&A: Researchers discuss potential solutions for the feedback loop affecting scientific publishing

A new ecological model highlights how fluctuating environments push microbes to work together

Chapman University researcher warns of structural risks at Grand Renaissance Dam putting property and lives in danger

Courtship is complicated, even in fruit flies

Columbia announces ARPA-H contract to advance science of healthy aging

New NYUAD study reveals hidden stress facing coral reef fish in the Arabian Gulf

36 months later: Distance learning in the wake of COVID-19

Blaming beavers for flood damage is bad policy and bad science, Concordia research shows

The new ‘forever’ contaminant? SFU study raises alarm on marine fiberglass pollution

Shorter early-life telomere length as a predictor of survival

Why do female caribou have antlers?

How studying yeast in the gut could lead to new, better drugs

Chemists thought phosphorus had shown all its cards. It surprised them with a new move

A feedback loop of rising submissions and overburdened peer reviewers threatens the peer review system of the scientific literature

Rediscovered music may never sound the same twice, according to new Surrey study

Ochsner Baton Rouge expands specialty physicians and providers at area clinics and O’Neal hospital

New strategies aim at HIV’s last strongholds

Ambitious climate policy ensures reduction of CO2 emissions

Frontiers in Science Deep Dive webinar series: How bacteria can reclaim lost energy, nutrients, and clean water from wastewater

UMaine researcher develops model to protect freshwater fish worldwide from extinction

Illinois and UChicago physicists develop a new method to measure the expansion rate of the universe

Pathway to residency program helps kids and the pediatrician shortage

How the color of a theater affects sound perception

Ensuring smartphones have not been tampered with

Overdiagnosis of papillary thyroid cancer

Association of dual eligibility and medicare type with quality of postacute care after stroke

Shine a light, build a crystal

[Press-News.org] Laser-powered 'needle' promises pain-free injectionsOptical technology gives a sci-fi twist to traditional medicine