(Press-News.org) Spintronic technology, in which data is processed on the basis of electron "spin" rather than charge, promises to revolutionize the computing industry with smaller, faster and more energy efficient data storage and processing. Materials drawing a lot of attention for spintronic applications are dilute magnetic semiconductors – normal semiconductors to which a small amount of magnetic atoms is added to make them ferromagnetic. Understanding the source of ferromagnetism in dilute magnetic semiconductors has been a major road-block impeding their further development and use in spintronics. Now a significant step to removing this road-block has been taken.

A multi-institutional collaboration of researchers led by scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab), using a new technique called HARPES, for Hard x-ray Angle-Resolved PhotoEmission Spectroscopy, has investigated the bulk electronic structure of the prototypical dilute magnetic semiconductor gallium manganese arsenide. Their findings show that the material's ferromagnetism arises from both of the two different mechanisms that have been proposed to explain it.

"This study represents the first application of HARPES to a forefront problem in materials science, uncovering the origin of the ferromagnetism in the so-called dilute magnetic semiconductors," says Charles Fadley, the physicist who led the development of HARPES. "Our results also suggest that the HARPES technique should be broadly applicable to many new classes of materials in the future."

Fadley, who holds joint appointments with Berkeley Lab's Materials Sciences Division and the University of California (UC) Davis where he is a Distinguished Professor of Physics, is the senior author of a paper describing this work in the journal Nature Materials. The paper is titled "Bulk electronic structure of the dilute magnetic semiconductor GaMnAs through hard X-ray angle-resolved photoemission." The lead and corresponding author is Alexander Gray, formerly with Fadley's research group and now with the Stanford University and the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

For the semiconductors used in today's computers, tablets and smart phones, etc., once a device is fabricated it is the electronic structures below the surface, in the bulk of the material or in buried layers, that determine its effectiveness. HARPES, which is based on the photoelectric effect described in 1905 by Albert Einstein, enables scientists to study bulk electronic effects with minimum interference from surface reactions or contamination. It also allows them to probe buried layers and interfaces that are ubiquitous in nanoscale devices, and are key to smaller logic elements in electronics, novel memory architectures in spintronics, and more efficient energy conversion in photovoltaic cells.

"The key to probing the bulk electronic structure is using hard x-rays, which are x-rays with sufficiently high photon energies to eject photoelectrons from deep beneath the surface of a solid material," says Gray, who worked with Fadley to develop the HARPES technique. "High-energy photons impart high kinetic energies to the ejected photoelectrons, enabling them to travel longer distances within the solid. The result is that more of the signal originating from the bulk will be detected by the analyzer."

In this new study, Gray and Fadley and their collaborators, used HARPES to shed important new light on the electronic bulk structure of gallium manganese arsenide (GaMnAs). As a semiconductor, gallium arsenide is second only to silicon in widespread use and importance. If a few percent of the gallium atoms in this semiconductor are replaced with atoms of manganese the result is a dilute magnetic semiconductor. Such materials would be especially well-suited for further development into spintronic devices if the mechanisms behind their ferromagnetism were better understood.

"Right now the temperature at which gallium manganese arsenide operates as a dilute magnetic semiconductor is 170 Kelvin," Fadley says. "Understanding the actual mechanism by which the magnetic moments of individual manganese atoms are coupled so as to become ferromagnetic is critical to being able to design future materials that would operate at room temperature."

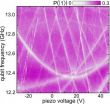

The two prevailing theories behind the origin of ferromagnetism in GaMnAs and other dilute magnetic semiconductors are the "p-d exchange model" and the "double exchange model." According to the p-d exchange model, ferromagnetism is mediated by electrons residing in the valence bands of gallium arsenide whose influence extends through the material to other manganese atoms. The double exchange model holds that the magnetism-mediating electrons reside in a separate impurity band created by doping the gallium arsenide with manganese. These electrons in effect jump back and forth between two manganese atoms so as to lower their energy when their ferromagnetic magnets are parallel.

"Our bulk-sensitive HARPES measurements revealed that the manganese-induced impurity band is located mostly between the gallium arsenide valence-band maximum and the Fermi level, but the manganese states are also merged with the gallium arsenide valence bands," Gray says. "This is evidence that the two mechanisms co-exist and both act to give rise to ferromagnetism."

Adds Fadley, "We now have a better fundamental understanding of electronic interactions in dilute magnetic semiconductors that can suggest future materials with different parent semiconductors and different magnetic dopants. HARPES should provide an important tool for characterizing these future materials."

Gray and Fadley conducted this study using a high intensity undulator beamline at the SPring8 synchrotron radiation facility in Hyogo, Japan, which is operated by the Japanese National Institute for Materials Sciences. New HARPES studies are now underway at Berkeley Lab's Advanced Light Source (ALS) using the Multi-Technique Spectrometer/Diffractometer endstation at the hard x-ray photoemission beamline (9.3.1).

INFORMATION:

Co-authoring the Nature Materials paper with Gray and Fadley were Jan Minár, Shigenori Ueda, Peter Stone, Yoshiyuki Yamashita, Jun Fujii, Juergen Braun, Lukasz Plucinski, Claus Schneider, Giancarlo Panaccione, Hubert Ebert, Oscar Dubon and Keisuke Kobayashi.

This research was primarily supported by the DOE Office of Science.

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory addresses the world's most urgent scientific challenges by advancing sustainable energy, protecting human health, creating new materials, and revealing the origin and fate of the universe. Founded in 1931, Berkeley Lab's scientific expertise has been recognized with 13 Nobel prizes. The University of California manages Berkeley Lab for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science. For more, visit www.lbl.gov.

DOE's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit the Office of Science website at science.energy.gov/.

Another advance on the road to spintronics

Berkeley Lab researchers unlock ferromagnetic secrets of promising materials

2012-10-15

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New merciful treatment method for children with brain tumors

2012-10-15

Children who undergo brain radiation therapy run a significant risk of suffering from permanent neurocognitive adverse effects. These adverse effects are due to the fact that the radiation often encounters healthy tissue. This reduces the formation of new cells, particularly in the hippocampus – the part of the brain involved in memory and learning.

Researchers at the University of Gothenburg's Sahlgrenska Academy have used a model study to test newer radiation therapy techniques which could reduce these harmful adverse effects. The researchers based their study on a ...

University of Tennessee collaborates in study: Dire drought ahead, may lead to massive tree death

2012-10-15

Evidence uncovered by a University of Tennessee, Knoxville, geography professor suggests recent droughts could be the new normal. This is especially bad news for our nation's forests.

For most, to find evidence that recent years' droughts have been record-breaking, they need not look past the withering garden or lawn. For Henri Grissino-Mayer he looks at the rings of trees over the past one thousand years. He can tell you that this drought is one of the worst in the last 600 years in America's Southwest and predicts worst are still to come.

Grissino-Mayer collaborated ...

NIH-funded study to test pneumococcal vaccine in older adults

2012-10-15

Researchers plan to see if a higher dose of a pneumococcal vaccine will create a stronger immune response in older adults who received an earlier generation vaccine against pneumonia and other pneumococcal diseases.

The study supported by the National Institutes of Health will compare two dosages of a pneumococcal vaccine approved for children ages 6 weeks to 5 years, and adults 50 and older. The trial will enroll up to 882 men and women ages 55 to 74.

The study is funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), part of NIH. Researchers ...

The voices in older literature speak differently today

2012-10-15

When we read a text, we hear a voice talking to us. Yet the voice changes over time. In his new book titled Poesins röster, Mats Malm, professor in comparative literature at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, shows that when reading older literature, we may hear completely different voices than contemporary readers did – or not hear any voices at all.

'When we read a novel written today, we hear a voice that speaks pretty much the same language we speak, and that addresses people and things in a way we are used to. But much happens as a text ages – a certain type of ...

Suicide attempts by poisoning found to be less likely around major holidays

2012-10-15

CINCINNATI—A joint study by University of Cincinnati Department of Emergency Medicine and Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center researchers has found that, in contrast to popular opinion, major holidays are associated with a lower number of suicide attempts by poisoning.

The study found that holidays like Christmas and Thanksgiving may actually be protective against suicide attempts, possibly due to the increased family or social support structures present around those times. In contrast, New Year's Day had significantly higher numbers of suicide attempts by overdose.

"There ...

Computer interventions on college drinking don't last

2012-10-15

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Computer-delivered and face-to-face interventions both can help curb problematic college drinking for a little while, but only in-person encounters produce results that last beyond a few months, according to a new analysis of the techniques schools use to counsel students on alcohol consumption.

CDIs — computer-delivered interventions — have gained prominence on college campuses because they can reach a large number of students almost regardless of the size of a college's counseling staff, said Kate Carey, lead author of a systematic ...

UNH scientists provide window on space radiation hazards

2012-10-15

DURHAM, N.H. – Astrophysicists from the University of New Hampshire's Space Science Center (SSC) have created the first online system for predicting and forecasting the radiation environment in near-Earth, lunar, and Martian space environments. The near real-time tool will provide critical information as preparations are made for potential future manned missions to the moon and Mars.

"If we send human beings back to the moon, and especially if we're able to go to Mars, it will be critical to have a system like this in place to protect astronauts from radiation hazards," ...

Science: Quantum oscillator responds to pressure

2012-10-15

In the far future, superconducting quantum bits might serve as components of high-performance computers. Today already do they help better understand the structure of solids, as is reported by researchers of Karlsruhe Institute of Technology in the Science magazine. By means of Josephson junctions, they measured the oscillations of individual atoms "tunneling" between two positions. This means that the atoms oscillated quantum mechanically. Deformation of the specimen even changed the frequency (DOI: 10.1126/science.1226487).

"We are now able to directly control the frequencies ...

Gene suppression can reduce cold-induced sweetening in potatoes

2012-10-15

This press release is available in Spanish.Preventing activity of a key enzyme in potatoes could help boost potato quality by putting an end to cold-induced sweetening, according to U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) scientists.

Cold-induced sweetening, which occurs when potatoes are put in long-term cold storage, causes flavor changes and unwanted dark colors in fried and roasted potatoes. But long-term cold storage is necessary to maintain an adequate supply of potatoes throughout the year.

Agricultural Research Service (ARS) scientists found that during cold ...

Fearful flyers willing to pay more and alter flight plans, according to travel study

2012-10-15

BEER-SHEVA, ISRAEL, October 15, 2012 -- Fearful flyers seek flight attributes that may be primarily reassuring, such as schedule, aircraft size and carrier origin, but have little effect on the low, actual risk according to a study published in the Journal of Travel Research.

People with fear of flying (FOF) are willing to pay more for a number of choices that help them alleviate their fear, according to the study by researchers at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev (BGU), The Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Technion Israel Institute of Technology.

According to ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Heart attack deaths rose between 2011 and 2022 among adults younger than age 55

Will melting glaciers slow climate change? A prevailing theory is on shaky ground

New treatment may dramatically improve survival for those with deadly brain cancer

Here we grow: chondrocytes’ behavior reveals novel targets for bone growth disorders

Leaping puddles create new rules for water physics

Scientists identify key protein that stops malaria parasite growth

Wildfire smoke linked to rise in violent assaults, new 11-year study finds

New technology could use sunlight to break down ‘forever chemicals’

Green hydrogen without forever chemicals and iridium

Billion-DKK grant for research in green transformation of the built environment

For solar power to truly provide affordable energy access, we need to deploy it better

Middle-aged men are most vulnerable to faster aging due to ‘forever chemicals’

Starving cancer: Nutrient deprivation effects on synovial sarcoma

Speaking from the heart: Study identifies key concerns of parenting with an early-onset cardiovascular condition

From the Late Bronze Age to today - Old Irish Goat carries 3,000 years of Irish history

Emerging class of antibiotics to tackle global tuberculosis crisis

Researchers create distortion-resistant energy materials to improve lithium-ion batteries

Scientists create the most detailed molecular map to date of the developing Down syndrome brain

Nutrient uptake gets to the root of roots

Aspirin not a quick fix for preventing bowel cancer

HPV vaccination provides “sustained protection” against cervical cancer

Many post-authorization studies fail to comply with public disclosure rules

GLP-1 drugs combined with healthy lifestyle habits linked with reduced cardiovascular risk among diabetes patients

Solved: New analysis of Apollo Moon samples finally settles debate about lunar magnetic field

University of Birmingham to host national computing center

Play nicely: Children who are not friends connect better through play when given a goal

Surviving the extreme temperatures of the climate crisis calls for a revolution in home and building design

The wild can be ‘death trap’ for rescued animals

New research: Nighttime road traffic noise stresses the heart and blood vessels

Meningococcal B vaccination does not reduce gonorrhoea, trial results show

[Press-News.org] Another advance on the road to spintronicsBerkeley Lab researchers unlock ferromagnetic secrets of promising materials