(Press-News.org) On the road at night or on a tennis court at dusk, the eye can be deceived. Vision is not as sharp as in the light of day, and detecting a bicyclist on the road or a careening tennis ball can be tough.

New research reveals the key chemical process that corrects for potential visual errors in low-light conditions. Understanding this fundamental step could lead to new treatments for visual deficits, or might one day boost normal night vision to new levels.

Like the mirror of a telescope pointed toward the night sky, the eye's rod cells capture the energy of photons - the individual particles that make up light. The interaction triggers a series of chemical signals that ultimately translate the photons into the light we see.

The key light receptor in rod cells is a protein called rhodopsin. Each rod cell has about 100 million rhodopsin receptors, and each one can detect a single photon at a time.

Scientists had thought that the strength of rhodopsin's signal determines how well we see in dim light. But UC Davis scientists have found instead that a second step acts as a gatekeeper to correct for rhodopsin errors. The result is a more accurate reading of light under dim conditions.

A report on their research appears in the October issue of the journal Neuron in a study entitled "Calcium feedback to cGMP synthesis strongly attenuates single photon responses driven by long rhodopsin lifetimes."

Individual rhodopsin errors are relatively small in magnitude - on the order of a few hundredths of a second - but even this much biological noise can affect how well the signal gets transmitted to the rest of the brain, the researchers said.

The gatekeeper protects us from "seeing" more light than is actually there - a misreading that would have endangered an ice-age hunter, as it would a driver at dusk today. The correction may prevent the photon receptor from swamping the intricate chemical apparatus that leads to accurate light perception.

"The rhodopsin receptor is the site where physics meets biology - where a photon of light from the physical world must get interpreted for the nervous system," said Marie Burns, professor of ophthalmology and vision science at UC Davis School of Medicine and lead author of the study. "Biology is messy. Rhodopsin does a remarkable but not perfect job."

Burns and her colleagues studied rod cells in the laboratory and discovered that calcium plays the gatekeeper role.

They found that rhodopsin activity changed calcium levels in the cells and that over-active rhodopsins changed calcium levels at a faster rate than normal. This faster change led calcium to trigger a series of chemical steps to counter the over-active rhodopsin signal by producing an equal and opposite signal, thereby correcting false information before it gets sent on to the rest of the visual system.

They uncovered this fundamental new level of control by measuring how long individual rhodopsin receptors remained active in response to flashes of light, and then determining how much calcium's gatekeeping function modified the rhodopsin signals.

"Basic research like ours often doesn't translate to immediate clinical treatments for known diseases, but understanding fundamental processes has long-term significance," Burns said. "In the case of our research, this understanding can prove essential for progress on a range of vision deficits that are currently poorly understood and untreatable."

INFORMATION:

Colleagues in the research and co-authors on the paper include Owen Gross, a former doctoral student at UC Davis who is now at Oregon Health Sciences University, and Edward N. Pugh Jr., a professor in the Department of Cell Biology and Human Anatomy and Department of Physiology and Membrane Biology at the UC Davis School of Medicine.

END

Extreme 'housework' cuts the life span of female Komodo Dragons

An international team of researchers has found that female Komodo Dragons live half as long as males on average, seemingly due to their physically demanding 'housework' such as building huge nests and guarding eggs for up to six months.

The results provide important information on the endangered lizards' growth rate, lifestyle and population differences, which may help plan conservation efforts.

The Komodo dragon is the world's largest lizard. Their formidable body size enables them to serve as top predators ...

More people still die from cardiovascular disease than any other illness. Dubbed the number one killer and the silent killer, modern medicine has been researching and incorporating complementary and alternative approaches to help treat and in some cases reverse and hopefully prevent this health problem at an earlier stage of the disease. One of those modalities is meditation.

A new research review paper on the effects of the stress-reducing Transcendental Meditation (TM) technique on the prevention and treatment of heart disease among youth and adults provides the hard ...

Information technology and electronics are becoming entwined with our everyday lives in industry, the service sector, transport, logistics, health care, housing, education, and our leisure time, almost without our noticing it.

The changes are already apparent to consumers in the energy sector, for example: remotely readable meters are rapidly becoming more common, enabling developments such as new pricing models that encourage the reduction of carbon dioxide emissions. The remote control of machines and devices is experiencing substantial growth and spreading to smaller ...

Active surveillance of small kidney masses is a safe and effective alternative to immediate surgery, with similar overall and cancer specific survival rates, according to a study published in the November issue of the urology journal BJUI.

The technique is primarily used to treat elderly patients who have complex health issues or decline surgery. But researchers from the Department of Urology at Churchill Hospital, Oxford, UK, say that the results of their study suggest that active surveillance could safely be extended to other selected patients.

"The incidence ...

Governments and institutions should focus on developing adaption policies to address and mitigate against the negative impact of global warming, rather than putting the emphasis on carbon trading and capping greenhouse-gas emissions, argue Johannesburg-based Wits University geoscientist Dr Jasper Knight and Dr Stephan Harrison from the University of Exeter in the United Kingdom.

"At present, governments' attempts to limit greenhouse-gas emissions through carbon cap-and-trade schemes and to promote renewable and sustainable energy sources are prob¬ably too late to arrest ...

A command doctrine used by the US military and NATO designed to warn personnel of Nuclear, Chemical and Biological (NBC) hazards could be overly conservative and degrade war fighting effectiveness or, under certain conditions, risk lives because it is susceptible to changes in wind direction and speed that happen in periods shorter than its two-hourly updates.

Writing in the International Journal of Environmental Pollution, Nathan Platt and Leo Jones of the Institute for Defense Analyses, in Alexandria, Virginia explain how "Allied Tactical Publication-45(C)" relies on ...

Pfizer Consumer Healthcare is very pleased that study investigators at Brigham and Women's Hospital, a teaching affiliate of Harvard Medical School, chose Centrum® Silver® for the Physicians' Health Study II. The Centrum® multivitamins' quality, among other factors, led investigators to choose Centrum® Silver® for inclusion in the study. Centrum® Silver® multivitamins currently available in stores have since been updated and improved to reflect advances in nutritional science.

In response to the Physicians' Health Study II findings shared this morning, Pfizer Consumer ...

Monozygotic twins have the same genome, that is, the same DNA molecule in both siblings. Despite being genetically identical, both twins may have different diseases at different times. This phenomenon is called "twin discordance". But how can people who have the same genetic sequence present different pathologies and at different ages? The explanation partly lies in the fact that the chemical signals added in the DNA to "switch off" or "switch on" genes can be different. These signals are known as epigenetic marks.

The research team led by Manel Esteller, director of ...

Athens, Ga. – Ecologists in the University of Georgia Odum School of Ecology have found that evolutionary diversity can be an effective method for identifying hotspots of mammal biodiversity. In a paper published Oct. 17 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, they report that evolutionary diversity can be an effective proxy for both the sheer number of species as well as their characteristics and ecological roles. Their findings could help conservation organizations better protect threatened species across the globe.

There are several measures of biodiversity, ...

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — There's a new contender in the race to find an inexpensive alternative to platinum catalysts for use in hydrogen fuel cells.

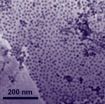

Brown University chemist Shouheng Sun and his students have developed a new material — a graphene sheet covered by cobalt and cobalt-oxide nanoparticles — that can catalyze the oxygen reduction reaction nearly as well as platinum does and is substantially more durable.

The new material "has the best reduction performance of any nonplatinum catalyst," said Shaojun Guo, postdoctoral researcher in Sun's lab and ...