(Press-News.org) MADISON – In 1986, when Voyager swept past Uranus, the probe's portraits of the planet were "notoriously bland," disappointing scientists, yielding few new details of the planet and its atmosphere, and giving it a reputation as a bore of the solar system.

Now, however, thanks to a new technique applied at the Keck Observatory, Uranus is coming into sharp focus through high-resolution infrared images, revealing in incredible detail the bizarre weather of the seventh planet from the sun.

The images were released in Reno, Nev. today (Oct. 17, 2012) at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society's Division of Planetary Sciences and provide the best look to date of Uranus's complex and enigmatic weather.

The planet's deep blue-green atmosphere is thick with hydrogen, helium and methane, Uranus's primary condensable gas. Winds blow mainly east to west at speeds up to 560 miles per hour, in spite of the small amounts of energy available to drive them. Its atmosphere is almost equal to Neptune's as the coldest in our solar system with cloud-top temperatures in the minus 360-degree Fahrenheit range, cold enough to freeze methane.

Large weather systems, which are probably much less violent than the storms we know on Earth, behave in bizarre ways on Uranus, explains Larry Sromovsky, a University of Wisconsin-Madison planetary scientist who led the new study using the Keck II telescope.

"Some of these weather systems," Sromovsky notes, "stay at fixed latitudes and undergo large variations in activity. Others are seen to drift toward the planet's equator while undergoing great changes in size and shape. Better measures of the wind fields that surround these massive weather systems are the key to unraveling their mysteries."

To get a better picture of atmospheric flow on Uranus, Sromovsky and colleagues Pat Fry, also of UW-Madison, Heidi Hammel of the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA), and Imke de Pater of the University of California at Berkeley, used new infrared techniques to detect smaller, more widely distributed weather features whose movements can help scientists trace the planet's pattern of blustery winds.

"We're seeing some new things that before were buried in the noise," says Sromovsky, a senior staff scientist at UW-Madison's Space Science and Engineering Center.

"My first reaction to these images was 'wow' and then my second reaction was WOW," says AURA's Heidi Hammel, a co-investigator on the new observations and an expert on the atmospheres of the solar system's outer planets. "These images reveal an astonishing amount of complexity in Uranus's atmosphere. We knew the planet was active, but until now much of the activity was masked by noise in our data."

The complexity of Uranus's weather is puzzling, Sromovsky explains. The primary driving mechanism must be solar energy because there is no detectable internal energy source. "But the sun is 900 times weaker there than on Earth because it is 30 times further from the sun, so you don't have the same intensity of solar energy driving the system," explains Sromovsky. "Thus the atmosphere of Uranus must operate as a very efficient machine with very little dissipation. Yet the weather variations we see seem to defy that requirement."

The new Keck II pictures of the planet, according to Sromovsky, are the "most richly detailed views of Uranus yet obtained by any instrument on any observatory. No other telescope could come close to producing this result."

Sromovsky and his colleagues used Keck II, located on the summit of Hawaii's 14,000-foot extinct volcano Mauna Kea, to capture a series of images that, when combined, help increase the signal to noise ratio and thus tease out weather features that are otherwise obscured. In two nights of observing under superb conditions, Sromovsky's group was able to obtain exposures of the planet that provide a clear view of the planet's cloudy features, including several new to science. The group used two different filters in an effort to characterize cloud features at different altitudes.

"The main objective was to find a larger number of cloud features by detecting those that were previously too subtle to be seen, so we could better define atmospheric motions," Sromovsky notes. New features found by the Wisconsin group include a scalloped band of clouds just south of Uranus's equator and a swarm of small convective features in the north polar regions of the planet, features that have never been seen in the southern polar regions.

"This is a very asymmetric situation," says the Wisconsin scientist. "There is certainly something different going on in those two polar regions."

One possible explanation, is that methane is pushed north by an atmospheric conveyor belt toward the pole where it wells up to form the convective features observed by Sromovsky's group.

"The 'popcorn' appearance of Uranus's pole reminds me very much of a Cassini image of Saturn," adds de Pater.

Saturn's South Pole is characterized by a polar vortex or hurricane surrounded by numerous small cloud features indicative of strong convection, analogous to the heavily precipitating clouds encircling the eye of terrestrial hurricanes, she notes. Her group suggested a similar phenomenon would be present on Neptune, based upon Keck observations of that planet.

"Perhaps we will also see a vortex at Uranus's pole when it comes into view," she says.

The phenomena may be seasonal, Sromovsky notes, but the group has so far been unable to establish a clear seasonal trend in the winds of Uranus.

"Uranus is changing," he says. "We don't expect things at the north pole to stay the way they are now."

The scalloped band of clouds near the planet's equator may indicate atmospheric instability or wind shear: "This is new and we don't fully understand what it means. We haven't seen it anywhere else on Uranus."

###

-- Terry Devitt (608) 262-8282, trdevitt@wisc.edu

Note: An image to accompany this story is available at http://www.news.wisc.edu/newsphotos/uranus2012.html

END

MINNEAPOLIS / ST. PAUL (10/17/2012) —An international team of researchers, including a University of Minnesota scientist, has developed an integrated physical, genetic and functional sequence assembly of the barley genome, one of the world's most important and genetically complex cereal crops. Results are published in today's issue of Nature.

The advance will give researchers the tools to produce higher yields, improve pest and disease resistance, and enhance the nutritional value of barley.

Importantly, it also will "accelerate breeding improvements to help barley ...

CHICAGO—Consumers are increasingly demanding the development of ready-to-eat gluten and lactose-free food products that meet their needs and help improve their health. A recent study in Journal of Food Science, published by the Institute of Food Technologists (IFT), shows how new white sauce formulations are being created to meet these demands.

Consumers with celiac disease often find that gluten-free products are of inferior quality compared with their traditional, non-gluten-free counterparts. Traditional white sauce is made with milk, flour or starch, oil, and salt. ...

CHICAGO- With over a thousand different varieties of mangoes to choose from, selecting the right variety for mango products can be a daunting task. A new study in the Journal of Food Science, published by the Institute of Food Technologists (IFT), explores the impact that processing has on the flavor and texture of mango varieties. Findings suggest that processing plays an important role in determining the flavor and texture of the final product.

Researchers at Kansas State University studied the flavor and texture of four different mango varieties as they were processed ...

Salt marshes have been disintegrating and dying over the past two decades along the U.S. Eastern Seaboard and other highly developed coastlines without anyone fully understanding why.

This week in the journal Nature, scientist Linda Deegan of the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) in Woods Hole, Mass., and colleagues report that nutrients--such as nitrogen and phosphorus from septic and sewer systems and lawn fertilizers--can cause salt marsh loss.

"Salt marshes are a critical interface between the land and sea," Deegan says. "They provide habitat for fish, birds ...

New research from Mount Sinai School of Medicine sheds light on how overeating can cause a malfunction in brain insulin signaling, and lead to obesity and diabetes. Christoph Buettner, MD, PhD, Associate Professor of Medicine (Endocrinology, Diabetes and Bone Disease) and his research team found that overeating impairs the ability of brain insulin to suppress the breakdown of fat in adipose tissue.

In previous research Dr. Buettner's team established that brain insulin is what suppresses lipolysis, a process during which triglycerides in fat tissue are broken down and ...

CHICAGO—According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 63 percent of the deaths that occurred in 2008 were attributed to non-communicable chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, certain cancers, Type 2 diabetes and obesity—for which poor diets are contributing factors. Yet people that live in societies that eat healthy, plant-based diets rarely fall victim to these ailments. Research studies have long indicated that a high consumption of plant foods is associated with lower incidents of chronic disease. In the October issue of Food Technology magazine, Senior ...

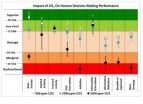

Overturning decades of conventional wisdom, researchers at the Department of Energy's Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) have found that moderately high indoor concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO2) can significantly impair people's decision-making performance. The results were unexpected and may have particular implications for schools and other spaces with high occupant density.

"In our field we have always had a dogma that CO2 itself, at the levels we find in buildings, is just not important and doesn't have any direct impacts on people," said Berkeley ...

Nano-ribbons of silicon configured so the atoms resemble chicken wire could hold the key to ultrahigh density data storage and information processing systems of the future.

This was a key finding of a team of scientists led by Paul Snijders of the Department of Energy's Oak Ridge National Laboratory. The researchers used scanning tunneling microscopy and spectroscopy to validate first principle calculations – or models – that for years had predicted this outcome. The discovery, detailed in New Journal of Physics, validates this theory and could move scientists closer ...

Los Angeles, CA (October 17, 2012)- When it comes to analyzing gender stereotypes in the media, studies have shown that photographs of men focus on male faces while photographs of women are more focused on women's bodies. A recent study from Psychology of Women Quarterly, a SAGE journal, finds that this type of "face-ism" is even more extreme in cultures with less educational, professional, and political gender discrimination.

"Being in a relatively egalitarian cultural context does not shield politicians from this face-ism bias; in fact, it exacerbates it," wrote study ...

NEW BRUNSWICK, N.J. – A Rutgers study of recent New Jersey college and university graduates with disabilities has found that students attributed their academic success to a combination of possessing such strong personality traits as self-advocacy and perseverance, and their relationship with a faculty or staff mentor.

Accessing campus accommodations was not a major issue but learning about such help "was not always the smoothest process," they noted. The research also determined that students mainly used campus resources for assistance rather than a combination of college ...