New paper examines shifting gears in the circadian clock of the heart

2012-10-24

(Press-News.org) A new study conducted by a team of scientists led by Giles Duffield, assistant professor of biological sciences and a member of the Eck Institute for Global Health at the University of Notre Dame focuses on the circadian clock of the heart, and used cultured heart tissue. The results of the new study have implications for cardiovascular health, including daily changes in responses to stress and the effect of long-term rotational shift work.

Previous studies by a research group at the University of Geneva demonstrated a role for glucocorticoids in shifting the biological clock, and characterized this effect in the liver.

The new Notre Dame study, which appears in Oct. 23 edition of journal PLoS ONE, reveals that time-of-day specific treatment with a synthetic glucocorticoid, known as dexamethasone, could shift the circadian rhythms of atria samples, but the time specific effect on the direction of the shifts was different from the liver. For example, when glucocorticoid treatment produces advances of the liver clock, in the atria it produces delays.

"We treated cardiac atrial explants around the clock and produced what is known as a phase response curve, showing the magnitude of the shifting of the clock dependent upon the time of day the treatment is delivered," Duffield said.

Glucocorticoids are steroid hormones produced by the adrenal cortex that then circulate in the blood and regulate aspects of glucose metabolism and immune system function, amongst other things. Glucocorticoid receptors (GRs) that are activated by the hormone, are found in many of our body's cells.

The researchers determined the temporal state of the circadian clock by monitoring the rhythmic expression of clock genes period 1 and period 2 in living tissues derived from transgenic mice.

"Our data highlights the sensitivity of the body's major organs to GR signaling, and in particular the heart," Duffield said. "This could be problematic for users of synthetic glucocorticoids, often used to treat chronic inflammation. Also the differences we observe between important organ systems such as the heart and liver might explain some of the internal disturbance to the synchrony between these tissues that contain their own internal clocks that can occur during shift-work and jet lag. For example, at some point in the time zone transition your brain might be in the time zone of Sydney Australia, your heart in Hawaii and your liver still in Los Angeles. It is important to note that approximately 16% of the US and European work forces undertake some form of shift work.

"Circadian biologists often are thought to be focused on finding a cure to actual 'jet lag', when in fact, certain types of shift work schedules are effectively producing a jet lag response in our body on a weekly basis, and therefore this chronically influences a large part of our population in the modern industrialized world."

The other interesting finding was that even removing and replacing the chemically defined tissue growth media (including using the same medium sample), produced shifts of the circadian clock, although these were somewhat smaller shifts than those produced by the synthetic glucocorticoid treatment.

The authors make an interesting proposal: that these "media exchange" shifts are in part caused by mechanical stimulation to the heart tissue produced by simply removing and replacing the very same media. Although the research is in its early phase, the hypothesis does highlight the potential for mechanical stretch of the atria to be a mechanism through which the circadian clock of the heart could be shifted to a new phase of the 24 hour day. There are in fact precedents for this, in that the walls of the cardiac atria already contain stretch receptors that are associated with the control of atrial natriuretic peptide hormone release.

"Least we forget, the heart by nature is mechanical, serving as the pump for the cardiovascular system," Duffield said.

Simple rigorous exercise in the healthy human or stress that can raise heart rate and increase cardiac stroke volume (through activation of the sympathetic nervous system), might produce such a phase shifting effect by acting through such a stretch mechanism. Further, this response is likely to be time of day specific, and the phase response curve to medium treatment that the authors generated in vitro would also predict at what time of the 24 hour day such shifts might occur.

The authors are however cautious about the interpretation of their data, as much of this mechanical shift hypothesis has yet to be tested.

It is already know that the heart contains a cell autonomous biological clock and that there are changes across the 24 hour day in cardiac function such as tissue remodeling, what cultured heart muscle cells known as cardiomyocytes metabolize, and differences in responses to physiological demands. The incidence of cardiovascular illness changes over the 24 hour day, with most heart attacks occurring in the morning. Obviously the results of the new study have implications for cardiovascular health, including daily changes in responses to stress and the effect of long-term rotational shift work.

"Put simply, many of our organ systems, specialized in their own way to serve particular functions, are effectively different in their activities and responses across the 24 hour day," said Duffield. "The circadian clock controls these rhythmic processes in each cell and tissue. The components of our body such as the heart, liver and brain, can be divided up as to function differentially not only in a spatial sense but also temporally."

Duffield, the scientific team principle investigator, stressed that the work was a team effort and highlights the important contributions of postdoctoral researcher Daan van der Veen, now a lecturer at the University of Surrey (United Kingdom), and visiting graduate students from Nankai University (P.R. China), Yang Xi and Jinping Shao, who is now a lecturer at Zhengzhou University School of Medicine. The work was funded by grants from the American Heart Association and the National Institute for General Medical Sciences.

###

Information on the University of Geneva group's research can be found at http://www.sciencemag.org/content/289/5488/2344.abstract.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Droplet response to electric voltage in solids exposed

2012-10-24

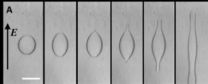

DURHAM, N.C. – For the first time, scientists have observed how droplets within solids deform and burst under high electric voltages.

This is important, the Duke University engineers who made the observations said, because it explains a major reason why such materials as insulation for electrical power lines eventually fail and cause blackouts. This observation not only helps scientists develop better insulation materials, but could also lead to such positive developments as "tunable" lenses for eyes.

As the voltage increases, water droplets, or air bubbles, within ...

Analysis of dinosaur bone cells confirms ancient protein preservation

2012-10-24

A team of researchers from North Carolina State University and the Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) has found more evidence for the preservation of ancient dinosaur proteins, including reactivity to antibodies that target specific proteins normally found in bone cells of vertebrates. These results further rule out sample contamination, and help solidify the case for preservation of cells – and possibly DNA – in ancient remains.

Dr. Mary Schweitzer, professor of marine, earth and atmospheric sciences with a joint appointment at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, ...

NJIT math professor calls Detroit Tigers a favorite to win World Series

2012-10-24

Since the Major League Baseball Division Series and League Championship Series have determined which teams will compete in the World Series, NJIT Math Professor Bruce Bukiet has again analyzed the probability of each team taking the title.

"The Detroit Tigers have a solid advantage over the San Francisco Giants. The Tigers, who surprisingly swept the New York Yankees in four straight games in the American League Championship Series to reach the World Series, have a 58 percent chance of beating the Giants in the best of seven series," he said.

At the season's start, ...

Medical recommendations should go beyond race, scholar says

2012-10-24

EAST LANSING, Mich. — Medical organizations that make race-based recommendations are misleading some patients about health risks while reinforcing harmful notions about race, argues a Michigan State University professor in a new paper published in the journal Preventive Medicine.

While some racial groups are on average more prone to certain diseases than the general population, they contain "islands" of lower risk that medical professionals should acknowledge, said Sean Valles, assistant professor in MSU's Lyman Briggs College and the Department of Philosophy.

For instance, ...

New Jersey's teen driver decals linked with fewer crashes

2012-10-24

A new study from The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) provides initial evidence that New Jersey's Graduated Driver Licensing (GDL) decal requirement lowers crash rates among intermediate (i.e., probationary) teen drivers and supports the ability of police to enforce GDL provisions. The study, which linked New Jersey's licensing and crash record databases to measure effects of the requirement, was published today in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine. Crash involvement of an estimated 1,624 intermediate drivers was prevented in the first year after the ...

Leaner Navy looking at future technology, fleet size and sequestration

2012-10-24

ARLINGTON, Va.—Adm. Mark Ferguson, vice chief of naval operations, headlined the opening of the ONR (Office of Naval Research) Naval S&T (science and technology) Partnership Conference and ASNE Expo Oct. 22, 2012, and highlighted the importance of innovative S&T programs being developed by the Navy. He also offered a revealing look at the potential future for the Navy if sequestration, or automatic defense cuts, goes into effect in January.

Speaking to a capacity crowd as keynote speaker, Ferguson said the Navy is already working hard to do more across the globe—with ...

Local wildlife is important in human diets

2012-10-24

Animals like antelope, frogs and rodents may be tricky to catch, but they provide protein in places where traditional livestock are scarce. According to the authors of a new paper in Animal Frontiers, meat from wild animals is increasingly important in central Africa.

"The elephant or hippopotamus may provide food for an entire community, smaller antelope may feed a family, while a rat or lizard may quell the hunger of an individual. Alternatively, these species are often sold on the road side or at local markets to supply a much needed source of cash revenue," write ...

Helping North America's marine protected areas adapt to a changing climate

2012-10-24

This press release is available in French and Spanish.Tampa, Florida, 23 October 2012—Top marine predators like tuna and sharks are suffering from the effects of climate change as the availability of prey decreases and the spatial distribution of their prey shifts. Countless other marine plants and animals are also affected.

One way to adapt to or mitigate these changes is to design marine protected areas (MPA) and MPA networks that integrate these and other climate-related considerations. Accordingly, the Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC) has published Scientific ...

Mercyhurst University study to identify levels of sucralose in Erie beach waters

2012-10-24

ERIE, Pa. - Researchers at Mercyhurst University continue to investigate the presence of potentially harmful chemicals in the beach waters of Presque Isle State Park and have added a new one to their list: sucralose. A chlorinated form of sucrose found in artificial sweeteners, sucralose is used in an estimated 4,500 products ranging from Halloween candies to diet sodas.

Studies suggest that approximately 95 percent of ingested sucralose is not metabolized by the body and is excreted into the water supply, said Dr. Amy Parente, assistant professor of chemistry and biochemistry ...

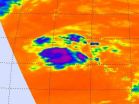

NASA view of Atlantic's Tropical Depression 19 shows backwards 'C' of strong storms

2012-10-24

Infrared imagery from the AIRS instrument on NASA's Aqua satellite revealed that the strongest thunderstorms within the Atlantic Ocean's Tropical Depression 19 seem to form a backwards letter "C" stretching from northeast to southeast around the storm's center. That "C" is a band of thunderstorms around the eastern side of the storm.

Infrared satellite imagery taken on Oct. 22 at 12:23 p.m. EDT, from the Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) instrument showed that the strongest thunderstorms in Tropical Depression 19 stretched from the northeast to the southeast of the ...