(Press-News.org) Researchers have identified several genes that are linked to one of the most lethal forms of uterine cancer, serous endometrial cancer. The researchers describe how three of the genes found in the study are frequently altered in the disease, suggesting that the genes drive the development of tumors. The findings appear in the Oct. 28, 2012, advance online issue of Nature Genetics. The team was led by researchers from the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), part of the National Institutes of Health.

Cancer of the uterine lining, or endometrium, is the most commonly diagnosed gynecological malignancy in the United States. Also called endometrial cancer, it is diagnosed in about 47,000 American women and leads to about 8,000 deaths each year.

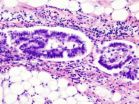

Each of its three major subtypes — endometrioid, serous and clear-cell —is caused by a different constellation of genetic alterations and has a different prognosis. Endometrioid tumors make up about 80 percent of diagnosed tumors. Surgery often is a complete cure for women with the endometrioid subtype, since doctors usually diagnose these cases at an early stage.

Compared to other subtypes, the 2 to 10 percent of uterine cancers that comprise the serous subtype do not respond well to therapies. The five-year survival rate for serous endometrial cancer is 45 percent, compared to 65 percent for clear-cell and 91 percent for endometrioid subtypes. Serous and clear-cell endometrial tumor subtypes are clinically aggressive and quickly advance beyond the uterus.

"Serous endometrial tumors can account for as much as 39 percent of deaths from endometrial cancer," said Daphne W. Bell, Ph.D., an NHGRI investigator and the paper's senior author. Dr. Bell heads the Reproductive Cancer Genetics Section of NHGRI's Cancer Genetics Branch.

To determine which genes are altered in serous endometrial cancer, Dr. Bell and her team undertook a comprehensive genomic study of tumors by sequencing their exomes, the critical 1 to 2 percent of the genome that codes for proteins.

"Exome sequencing is a powerful tool for revealing important insights about this form of cancer that exacts such a high toll for thousands of women," said NHGRI Scientific Director Dan Kastner, M.D., Ph.D. "This study pinpoints genetic alterations that may be essential for onset and progression of uterine cancers and may eventually lead to new therapeutic targets."

Dr. Bell's team focused on the rarer, more aggressive forms of endometrial cancer. They began their study by examining serous tumor tissue and matched normal tissue from 13 patients. National Cancer Institute and Massachusetts General Hospital pathologists processed the 26 tissue samples, which subsequently underwent whole-exome sequencing at the NIH Intramural Sequencing Center.

With the exome data in hand, the researchers filtered through millions of data points to locate alterations, or mutations. They disqualified from the analysis any mutation found in a tumor and its matched healthy tissue, looking expressly for mutations that occurred exclusively in the tumor cells. They also eliminated one of the 13 tumors from analysis because its exome had hundreds more unique mutations than any other tumor.

The researchers detected more than 500 somatic mutations within the remaining 12 tumors. They next looked for genes that were mutated in more than one of the tumors. An alteration that occurs in more than one tumor is more likely to be relevant to the development of the cancer than a unique alteration.

"When you identify a set of mutations, they could either be drivers that have caused the cancer or incidental passengers that are of no consequence; our goal is to identify the drivers," Dr. Bell explained. "One way to do this is to home in on genes that are mutated in more than one tumor, because we know from experience that frequently mutated genes are often driver genes."

The team felt confident that alterations in nine genes could be driver genes in serous endometrial cancer. Three of the nine genes had previously been recognized by researchers in the cancer genetics field as a cause of serous endometrial cancer. To get a clearer picture of driver gene status among the other six genes, the researchers sequenced each gene in 40 additional serous endometrial tumors. They discovered that three of the six genes — CHD4, FBXW7 and SPOP — are altered at a statistically high frequency in serous endometrial cancer.

The team also found that this set of three genes is mutated in 40 percent of the serous endometrial cancer tumors and in 15 to 26 percent of the other endometrial cancer subtypes.

Probing still further, the researchers looked for the same genes highlighted by their exome sequencing study within databases that organize genes according to their biological function. They found an enrichment of genes involved in chromatin remodeling, the dynamic process by which the contents of the cell nucleus, including DNA, are packaged and modified. Chromatin remodeling enables tightly packaged DNA to be accessed for the expression of genes. Intriguingly, CHD4 was one of the genes that formed the chromatin-remodeling cluster.

"We sequenced the other genes that make up this cluster and, as a set, these genes are frequently mutated in both serous and clear-cell endometrial tumors," said Dr. Bell.

They also noted frequent mutations in genes that regulate a process known as ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation. The process targets unneeded proteins for destruction, and thus prevents them from accumulating within the cell. Left to accumulate, some of the target proteins are known to drive cancer formation. FBXW7 and SPOP are both known to play a role in binding to the unneeded proteins and targeting them for destruction.

Many of the FBXW7 gene mutations that Dr. Bell's team identified are known in other cancers to be driver mutations that prevent the FBXW7 protein from binding to its target protein. Dr. Bell believes that altered SPOP may behave the same way. "All the mutations we found in SPOP are in the region that binds the target proteins" she said. "We suspect the mutations in SPOP might lead to the accumulation of the unneeded proteins within the cell. But that has to be tested."

The current findings build on the team's 2011 study that showed for the first time that alterations in the PIK3R1 gene occur in all subtypes of endometrial cancer and are most frequent in the more common endometrioid subtype.

"This discovery really changes our understanding of some of the genetic alterations that may contribute to this disease," Dr. Bell said, acknowledging that the findings are limited by the small number of tumors subjected to exome sequencing.

She noted that it is too early to make a direct connection between their findings and prospects for treatments for this aggressive form of uterine cancer.

INFORMATION:

For more information about endometrial cancer, go to http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/endometrial.

NHGRI is one of the 27 institutes and centers at the National Institutes of Health, an agency of the Department of Health and Human Services. The NHGRI Division of Intramural Research develops and implements technology to understand, diagnose and treat genomic and genetic diseases. Additional information about NHGRI can be found at its website, http://www.genome.gov.

About the National Institutes of Health (NIH): NIH, the nation's medical research agency, includes 27 institutes and centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIH is the primary federal agency conducting and supporting basic, clinical, and translational medical research, and is investigating the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit http://www.nih.gov.

NIH researchers identify novel genes that may drive rare, aggressive form of uterine cancer

Serous endometrial tumors account for some of the most difficult to treat cancers of the uterine lining

2012-10-29

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Key discovered to how chemotherapy drug causes heart failure

2012-10-29

HOUSTON - Doxorubicin, a 50-year-old chemotherapy drug still in widespread use against a variety of cancers, has long been known to destroy heart tissue, as well as tumors, in some patients.

Scientists have identified an unexpected mechanism via the enzyme Top2b that drives the drug's attack on heart muscle, providing a new approach for identifying patients who can safely tolerate doxorubicin and for developing new drugs. A team led by scientists at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center reports its findings about the general DNA-damaging drug today in the ...

How to make stem cells – nuclear reprogramming moves a step forward

2012-10-29

The idea of taking a mature cell and removing its identity (nuclear reprogramming) so that it can then become any kind of cell, holds great promise for repairing damaged tissue or replacing bone marrow after chemotherapy. Hot on the heels of his recent Nobel prize Dr John B. Gurdon has published today in BioMed Central's open access journal Epigenetics & Chromatin research showing that histone H3.3 deposited by the histone-interacting protein HIRA is a key step in reverting nuclei to a pluripotent type, capable of being any one of many cell types.

All of an individual's ...

US shale gas drives up coal exports

2012-10-29

US CO2 emissions from domestic energy have declined by 8.6% since a peak in 2005, the equivalent of 1.4% per year.

However, the researchers warn that more than half of the recent emissions reductions in the power sector may be displaced overseas by the trade in coal.

Dr John Broderick, lead author on the report from the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, comments: "Research papers and newspaper column inches have focussed on the relative emissions from coal and gas.

"However, it is the total quantity of CO2 from the energy system that matters to the climate. ...

Atrial fibrillation is a 'modifiable' risk factor for stroke

2012-10-29

Atrial fibrillation, whose prevalence continues to rise, was described last year as the "new epidemic" in cardiovascular disease, even though AF can be successfully controlled by the detection and management of risk factors, by rhythm control treatments, and by the use of antithrombotic therapies.(1) These therapies have been improved in the past few years by the introduction of new anticoagulant drugs, such that AF - like high blood pressure or smoking - may now be considered a "modifiable" risk factor for stroke, whose treatment can reduce the degree of risk.

Professor ...

Uncertainty of future South Pacific Island rainfall explained

2012-10-29

With greenhouse warming, rainfall in the South Pacific islands will depend on two competing effects – an increase due to overall warming and a decrease due to changes in atmospheric water transport – according to a study by an international team of scientists around Matthew Widlansky and Axel Timmermann at the International Pacific Research Center, University of Hawaii at Manoa. In the South Pacific, the study shows, these two effects sometimes cancel each other out, resulting in highly uncertain rainfall projections. Results of the study are published in the 28 October ...

Primates' brains make visual maps using triangular grids

2012-10-29

Primates' brains see the world through triangular grids, according to a new study published online Sunday in the journal Nature.

Scientists at Yerkes National Primate Research Center, Emory University, have identified grid cells, neurons that fire in repeating triangular patterns as the eyes explore visual scenes, in the brains of rhesus monkeys.

The finding has implications for understanding how humans form and remember mental maps of the world, as well as how neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's erode those abilities. This is the first time grid cells have ...

Mechanism found for destruction of key allergy-inducing complexes, Stanford researchers say

2012-10-29

STANFORD, Calif. — Researchers have learned how a man-made molecule destroys complexes that induce allergic responses — a discovery that could lead to the development of highly potent, rapidly acting interventions for a host of acute allergic reactions.

The study, which will be published online Oct. 28 in Nature, was led by scientists at the Stanford University School of Medicine and the University of Bern, Switzerland.

The new inhibitor disarms IgE antibodies, pivotal players in acute allergies, by detaching the antibody from its partner in crime, a molecule called ...

Yeast model offers clues to possible drug targets for Lou Gehrig's disease, study shows

2012-10-29

STANFORD, Calif. — Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also called Lou Gehrig's disease, is a devastatingly cruel neurodegenerative disorder that robs sufferers of the ability to move, speak and, finally, breathe. Now researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine and San Francisco's Gladstone Institutes have used baker's yeast — a tiny, one-celled organism — to identify a chink in the armor of the currently incurable disease that may eventually lead to new therapies for human patients.

"Even though yeast and humans are separated by a billion years of evolution, ...

Test developed to detect early-stage diseases with naked eye

2012-10-29

Scientists have developed a prototype ultra-sensitive sensor that would enable doctors to detect the early stages of diseases and viruses with the naked eye, according to research published today in the journal Nature Nanotechnology.

The team, from Imperial College London, report that their visual sensor technology is ten times more sensitive than the current gold standard methods for measuring biomarkers. These indicate the onset of diseases such as prostate cancer and infection by viruses including HIV.

The researchers say their sensor would benefit countries where ...

Nova Scotia research team proves peer pressure can be used for good

2012-10-29

Using peer mentors to enhance school-day physical activity in elementary aged students has been given an A+ from Nova Scotia researchers.

And the increased physical activity levels got top grades for significantly improving both academic test scores and cardiovascular fitness levels.

Funded principally by the Nova Scotia Research Foundation and supported by community partners including the Heart and Stroke Foundation, research by principal investigator Dr. Camille Hancock Friesen and her team at the Maritime Heart Center (MHC) found that peer mentors can significantly ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Medicare patients get different stroke care depending on plan, analysis reveals

Polyploidy-induced senescence may drive aging, tissue repair, and cancer risk

Study shows that treating patients with lifestyle medicine may help reduce clinician burnout

Experimental and numerical framework for acoustic streaming prediction in mid-air phased arrays

Ancestral motif enables broad DNA binding by NIN, a master regulator of rhizobial symbiosis

Macrophage immune cells need constant reminders to retain memories of prior infections

Ultra-endurance running may accelerate aging and breakdown of red blood cells

Ancient mind-body practice proven to lower blood pressure in clinical trial

SwRI to create advanced Product Lifecycle Management system for the Air Force

Natural selection operates on multiple levels, comprehensive review of scientific studies shows

Developing a national research program on liquid metals for fusion

AI-powered ECG could help guide lifelong heart monitoring for patients with repaired tetralogy of fallot

Global shark bites return to average in 2025, with a smaller proportion in the United States

Millions are unaware of heart risks that don’t start in the heart

What freezing plants in blocks of ice can tell us about the future of Svalbard’s plant communities

A new vascularized tissueoid-on-a-chip model for liver regeneration and transplant rejection

Augmented reality menus may help restaurants attract more customers, improve brand perceptions

Power grids to epidemics: study shows small patterns trigger systemic failures

Computational insights into the interactions of andrographolide derivative SRJ09 with histone deacetylase for the management of beta thalassemia

A genetic brake that forms our muscles

CHEST announces first class of certified critical care advanced practice providers awarded CCAPP Designation

Jeonbuk National University researchers develop an innovative prussian-blue based electrode for effective and efficient cesium removal

Self-organization of cell-sized chiral rotating actin rings driven by a chiral myosin

Report: US history polarizes generations, but has potential to unite

Tiny bubbles, big breakthrough: Cracking cancer’s “fortress”

A biological material that becomes stronger when wet could replace plastics

Glacial feast: Seals caught closer to glaciers had fuller stomachs

Get the picture? High-tech, low-cost lens focuses on global consumer markets

Antimicrobial resistance in foodborne bacteria remains a public health concern in Europe

Safer batteries for storing energy at massive scale

[Press-News.org] NIH researchers identify novel genes that may drive rare, aggressive form of uterine cancerSerous endometrial tumors account for some of the most difficult to treat cancers of the uterine lining