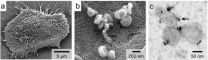

(Press-News.org) A novel miniature diagnostic platform using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) technology is capable of detecting minuscule cell particles known as microvesicles in a drop of blood. Microvesicles shed by cancer cells are even more numerous than those released by normal cells, so detecting them could prove a simple means for diagnosing cancer. In a study published in Nature Medicine, investigators at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Center for Systems Biology (CSB) demonstrate that microvesicles shed by brain cancer cells can be reliably detected in human blood through a combination of nanotechnology and their new NMR-based device.

"About 30 or 40 years ago, people noticed something in the bloodstream that they initially thought was some kind of debris or 'cell dust',"explains Hakho Lee, PhD, of the CSB, and co-senior author of the study with Ralph Weissleder, MD, PhD, director of the CSB. "But it has recently become apparent that these vesicles shed by cells actually harbor the same biomarkers as their parent cells."

Circulating tumor cells (CTCs) have been regarded as a potential key to improved cancer diagnosis, but Lee explains, "The problem with CTCs is that they are extremely rare, so finding them in the blood is like trying to find a needle in a haystack." Microvesicles on the other hand are abundant in the circulation and, unlike CTCs, are small enough to cross the blood/brain barrier, which means that they could be used to detect and monitor brain cancers, he adds.

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is the most common and most aggressive brain cancer in humans. By the time it is diagnosed, patients typically have less than 15 months to live. One of the biggest challenges with this condition is accurate disease monitoring to establish whether patients are responding to treatment. Currently, the only way to diagnose and monitor GBM is with biopsies and imaging tests, making long-term treatment monitoring difficult, invasive and impractical. To address this need, the CSB team sought to develop a simple blood test that could be used to easily monitor disease progression.

"The issue with microvesicles, however, is that they are very small, so there are not many technologies out there that can detect and molecularly profile them," explains Lee. "That is where our new technology comes in." By using nanotechnology to magnetically label microvesicles, and by adapting and improving equipment they developed last year to detect cancer cells with a miniature, hand-held NMR, the MGH researchers were able to reliably detect the tumor microvesicles in blood samples from mice bearing human GBM tumors and eventually in samples from human GBM patients.

Compared with other gold-standard techniques, this new technology demonstrated excellent detection accuracy. However, unlike other methods – which can be time-consuming and require much greater sample volumes as well as expertise to perform – NMR detection is quick and simple, potentially providing almost instant results from a small blood sample right in a doctor's office, the authors note. The MGH CSB team is currently extending this platform to other types of cancer and to other diseases such as bacterial infection. A number of clinical studies are currently ongoing, and others are in the planning stages, with the goal of eventually commercializing the technology.

"These microvesicles were found to be remarkably reliable biomarkers," confirms Weissleder. "They are very stable and abundant and appear to be extremely sensitive to treatment effects. In both animals and human patients, we were able to monitor how the number of cancer-related microvesicles in the bloodstream changed with treatment," explains Weissleder. "Even before an appreciable change in tumor size could be seen with imaging, we saw fewer microvesicles. It's like they are a harbinger of treatment response." Weissleder is a professor of Radiology and Lee an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School.

INFORMATION:

Huilin Shao of the MGH Center for Systems Biology is lead author of the Nature Medicine report. Additional co-authors are Jaehoon Chung, PhD, MGH CSB; Leonora Balaj and Xandra Breakefield, PhD, MGH Neurology; Fred Hochberg, MD, MGH Cancer Center; Alain Charest, PhD, Tufts University School of Medicine; Darell Bigner, MD, PhD, Duke University Medical Center; and Bob S. Carter, MD, PhD, University of California, San Diego. The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Massachusetts General Hospital, founded in 1811, is the original and largest teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School. The MGH conducts the largest hospital-based research program in the United States, with an annual research budget of more than $750 million and major research centers in AIDS, cardiovascular research, cancer, computational and integrative biology, cutaneous biology, human genetics, medical imaging, neurodegenerative disorders, regenerative medicine, reproductive biology, systems biology, transplantation biology and photomedicine. In July 2012, MGH moved into the number one spot on the 2012-13 U.S. News & World Report list of "America's Best Hospitals."

Detection, analysis of 'cell dust' may allow diagnosis, monitoring of brain cancer

System combining nanotechnology and NMR detects particles shed by brain tumors in bloodstream

2012-11-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Researchers discover 2 genetic flaws behind common form of inherited muscular dystrophy

2012-11-12

SEATTLE – An international research team co-led by a scientist at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center has identified two genetic factors behind the third most common form of muscular dystrophy. The findings, published online in Nature Genetics, represent the latest in the team's series of groundbreaking discoveries begun in 2010 regarding the genetic causes of facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy, or FSHD.

The team, co-led by Stephen Tapscott, M.D., Ph.D., a member of the Hutchinson Center's Human Biology Division, discovered that a rare variant of FSHD, called type ...

Touch-sensitive plastic skin heals itself

2012-11-12

Nobody knows the remarkable properties of human skin like the researchers struggling to emulate it. Not only is our skin sensitive, sending the brain precise information about pressure and temperature, but it also heals efficiently to preserve a protective barrier against the world. Combining these two features in a single synthetic material presented an exciting challenge for Stanford Chemical Engineering Professor Zhenan Bao and her team.

Now, they have succeeded in making the first material that can both sense subtle pressure and heal itself when torn or cut. Their ...

36 in one fell swoop -- researchers observe 'impossible' ionization

2012-11-12

This press release is available in German.

Using the world's most powerful X-ray laser in California, an international research team discovered a surprising behaviour of atoms: with a single X-ray flash, the group led by Daniel Rolles from the Center for Free-Electron Laser Science (CFEL) in Hamburg (Germany) was able to kick a record number of 36 electrons at once out of a xenon atom. According to theoretical calculations, these are significantly more than should be possible at this energy of the X-ray radiation. The team present their unexpected observations in the ...

'Groundwater inundation' doubles previous predictions of flooding with future sea level rise

2012-11-12

Scientists from the University of Hawaii at Manoa (UHM) published a study today in Nature Climate Change showing that besides marine inundation (flooding), low-lying coastal areas may also be vulnerable to "groundwater inundation," a factor largely unrecognized in earlier predictions on the effects of sea level rise (SLR). Previous research has predicted that by the end of the century, sea level may rise 1 meter. Kolja Rotzoll, Postdoctoral Researcher at the UHM Water Resources Research Center and Charles Fletcher, UHM Associate Dean, found that the flooded area in urban ...

Game changer for arthritis and anti-fibrosis drugs

2012-11-12

(SALT LAKE CITY)—In a discovery that can fundamentally change how drugs for arthritis, and potentially many other diseases, are made, University of Utah medical researchers have identified a way to treat inflammation while potentially minimizing a serious side effect of current medications: the increased risk for infection.

These findings provide a new roadmap for making powerful anti-inflammatory medicines that will be safer not only for arthritis patients but also for millions of others with inflammation-associated diseases, such as diabetes, traumatic brain injury, ...

CSHL-led team discovers new way in which plants control flower production

2012-11-12

Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y. – Flowers don't just catch our eyes, they catch those of pollinators like bees as well. They have to, in order to reproduce. Because plants need to maximize the opportunity for pollinators to gain access to their seeds, variations in the timing of flowering can have profound effects on flower, fruit, and seed production, and consequently agricultural yields.

We know that the major driving forces of flowering are external factors such as light and temperature. However, new research from CSHL Assistant Professor Zach Lippman, Ph.D. and his collaborators, ...

Mutations in genes that modify DNA packaging result in Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy

2012-11-12

A recent finding by medical geneticists sheds new light on how Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy develops and how it might be treated. More commonly known as FSHD, the devastating disease affects both men and women.

FSHD is usually an inherited genetic disorder, yet sometimes appears spontaneously via new mutations in individuals with no family history of the condition.

"People with the condition experience progressive muscle weakness and about 1 in 5 require wheelchair assistance by age 40," said Dr. Daniel G. Miller, University of Washington associate professor ...

Study provides recipe for 'supercharging' atoms with X-ray laser

2012-11-12

Researchers using the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory have found a way to strip most of the electrons from xenon atoms, creating a "supercharged," strongly positive state at energies previously thought too low.

The findings, which defy expectations and theory, could help scientists deliberately induce the high levels of damage needed to study extreme states of matter or ward off damage in samples they're trying to image. The results were reported this week in Nature Photonics.

While the ...

Why Antarctic sea ice cover has increased under the effects of climate change

2012-11-12

The first direct evidence that marked changes to Antarctic sea ice drift have occurred over the last 20 years, in response to changing winds, is published this week in the journal Nature Geoscience. Scientists from NERC's British Antarctic Survey (BAS) and NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), Pasadena California explain why, unlike the dramatic losses reported in the Arctic, the Antarctic sea ice cover has increased under the effects of climate change.

Maps created by JPL using over 5 million individual daily ice motion measurements captured over a period of 19 years ...

Did wild birds cause the 2010 deadly West Nile virus outbreak in Greece?

2012-11-12

In 2010, 35 people in Greece died from a West Nile virus (WNV) outbreak, with a further 262 laboratory-confirmed human cases. A new article published in BioMedCentral's open access journal Virology Journal examines whether wild or migratory birds could have been responsible for importing and amplifying the deadly virus.

WNV is a flavivirus of major public health concern, spread through the bite of infected mosquitoes. Discovered in Uganda in 1937, it was only sporadically reported up until the 1990s, after which disease outbreaks were reported world-over, leading to ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

How boron helps to produce key proteins for new cancer therapies

Writing the catalog of plasma membrane repair proteins

A comprehensive review charts how psychiatry could finally diagnose what it actually treats

Thousands of genetic variants shape epilepsy risk, and most remain hidden

First comprehensive sex-specific atlas of GLP-1 in the mouse brain reveals why blockbuster weight-loss drugs may work differently in females and males

When rats run, their gut bacteria rewrite the chemical conversation with the brain

Movies reconstructed from mouse brain activity

Subglacial weathering may have slowed Earth's escape from snowball Earth

Simple test could transform time to endometriosis diagnosis

Why ‘being squeezed’ helps breast cancer cells to thrive

Mpox immune test validated during Rwandan outbreak

Scientists pinpoint protein shapes that track Alzheimer’s progression

Researchers achieve efficient bicarbonate-mediated integrated capture and electrolysis of carbon dioxide

Study reveals ancient needles and awls served many purposes

Key protein SYFO2 enables 'self-fertilization’ of leguminous plants

AI tool streamlines drug synthesis

Turning orchard waste into climate solutions: A simple method boosts biochar carbon storage

New ACP papers say health care must be more accessible and inclusive for patients and physicians with disabilities

Moisture powered materials could make cleaning CO₂ from air more efficient

Scientists identify the gatekeeper of retinal progenitor cell identity

American Indian and Alaska native peoples experience higher rates of fatal police violence in and around reservations

Research alert: Long-read genome sequencing uncovers new autism gene variants

Genetic mapping of Baltic Sea herring important for sustainable fishing

In the ocean’s marine ‘snow,’ a scientist seeks clues to future climate

Understanding how “marine snow” acts as a carbon sink

In search of the room temperature superconductor: international team formulates research agenda

Index provides flu risk for each state

Altered brain networks in newborns with congenital heart disease

Can people distinguish between AI-generated and human speech?

New robotic microfluidic platform brings ai to lipid nanoparticle design

[Press-News.org] Detection, analysis of 'cell dust' may allow diagnosis, monitoring of brain cancerSystem combining nanotechnology and NMR detects particles shed by brain tumors in bloodstream