(Press-News.org) CAMBRIDGE, MA - Many species exhibit cooperative survival strategies — for example, sharing food or alerting other individuals when a predator is nearby. However, there are almost always freeloaders in the population who will take advantage of cooperators. This can be seen even among microbes such as yeast, where "cheaters" consume food produced by their neighbors without contributing any of their own.

In light of this, evolutionary biologists have long wondered why cooperation remains a viable survival strategy, since there will always be others who cheat. Now, MIT physicists have found a possible answer to this question: Among yeast, cooperative members of the population actually have a better chance of survival than cheaters when a competing species is introduced into an environment.

This experimental setup, in which yeast must coexist with a bacterial competitor, more closely mimics natural environments, where species often have to compete with one another for scarce food and other resources.

"It's very difficult to study these things in the truly natural context," says Jeff Gore, an assistant professor of physics at MIT and senior author of the new study, which appears in the journal Molecular Systems Biology on Nov. 13. "These experiments can act as a bridge between single-species experiments and very complicated ecosystem dynamics that are out there."

Hasan Celiker, an MIT graduate student in electrical engineering and computer science, is the paper's lead author.

Cheaters do prosper, sometimes

Gore and Celiker studied a strain of yeast that relies on small sugars such as glucose and fructose for nourishment. When yeast cells are grown in a test tube containing sucrose, some secrete an enzyme that breaks the sucrose down into smaller sugars, most of which diffuse away and are available to any nearby yeast cell.

In 2009, Gore and colleagues published a study showing that in a stable population of these yeast, freeloaders dominate. Only 14 percent of the yeast cells cooperate by secreting metabolic enzymes, while the rest enjoy the bounty of others' work.

In the new study, the researchers wanted to bring their experimental system closer to the complexity of natural environments. "Our approach is to start with the most simple system you can," Gore says. "Then we'd like to try to understand these more complicated interactions between different species, so as a baby step in that direction, we added a bacterial competitor."

This bacterial competitor consumes much of the sugar produced by the cooperative yeast, and also competes for other resources, such as nutrients. After these bacteria were added, the percentage of cooperators in the yeast population increased to about 45 percent.

This isn't because the yeast "decide" to become more cooperative, as humans might when faced with an external threat, Gore says. It's determined purely by genetics. "That's the point of doing experiments with microbial populations: There should be a mechanism that we can understand," he says.

Extra competition

In this case, the researchers found two mechanisms at work. First, in the face of extra competition for sugars, the cooperators have a slight advantage over cheaters because they have slightly easier access to the sugar they produce themselves.

A related mechanism involves population density. When bacteria are present, the overall yeast population stays smaller and is forced to spread out more, making it harder for the freeloaders to find food.

"The cheater cells can really spread when there are a lot of other yeast, because there's a lot of sugar out there for them. If there aren't very many yeast, then it's challenging for cheaters to spread," Gore says.

Though the experiment does not precisely replicate natural conditions, it does show that it is important to try to get as close to those conditions as possible, Gore says.

"If you just study something in isolation, such as yeast in a test tube, you might conclude that cooperation is very unstable," he says. "But if you look at these populations in the wild, where their densities are limited and they have to interact with all these other species, you might come to very different conclusions for how difficult it is for the cooperative behavior to survive."

In future studies, Gore hopes to add further complexity to the experimental microbial ecosystems, including varying the size of the yeast habitat.

###

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, a Pew Fellowship, a Foundational Questions in Evolutionary Biology grant, a Sloan Foundation Fellowship, and a Siebel Scholarship.

Written by Anne Trafton, MIT News Office

It pays to cooperate

2012-11-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

How online video stream quality affects viewer behavior

2012-11-13

AMHERST, Mass. – It may seem like common sense that the quality of online video streaming affects how willing viewers are to watch videos at a website. But until computer science researcher Ramesh Sitaraman at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and collaborators at Akamai developed a way to rigorously study the question, no one had been able to scientifically test the assumption.

They conducted the first large-scale study of its kind to quantitatively demonstrate how video stream quality causes changes in viewer behavior. "Video stream quality is a very big topic ...

Once the conflict is over, solidarity in alliances goes out of the window

2012-11-13

This press release is available in German.

It is not always wise to form an alliance while in a conflict or at war, especially when there is something to be shared afterward. Economists from the Max Planck Institute for Tax Law and Public Finance have now shown by game theory experiments that, as soon as the enemy is gone, in-group solidarity of alliances vanishes rapidly. Former brothers in arms fight even more vigorously over the spoils of a victory than strangers do. During the conflict, they expend together only half the effort of their enemy. Furthermore, when ...

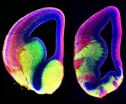

Watching the developing brain, scientists glean clues on neurological disorder

2012-11-13

CHAPEL HILL, N.C. – As the brain develops, each neuron must find its way to precisely the right spot to weave the intricate network of links the brain needs to function. Like the wiring in a computer, a few misplaced connections can throw off functioning for an entire segment of the brain.

A new study by researchers at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine reveals how some nerve cells, called interneurons, navigate during the development of the cerebral cortex. Mutations in a key gene behind this navigation system underlie a rare neurological disorder called ...

Glutamate neurotransmission system may be involved with depression risk

2012-11-13

Researchers using a new approach to identifying genes associated with depression have found that variants in a group of genes involved in transmission of signals by the neurotransmitter glutamate appear to increase the risk of depression. The report published in the journal Translational Psychiatry suggests that drugs targeting the glutamate system may help improve the limited success of treatment with current antidepressant drugs.

"Instead of looking at DNA variations one at a time, we looked at grouping of genes in the same biological pathways and found that a set ...

Baiting mosquitoes with knowledge and proven insecticides

2012-11-13

This press release is available in Spanish.

While one team of U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) scientists is testing the effectiveness of pesticides against mosquitoes, another group is learning how repellents work.

At the Agricultural Research Service (ARS) Center for Medical, Agricultural and Veterinary Entomology (CMAVE) in Gainesville, Fla., entomologist Sandra Allan is using toxic sugar-based baits to lure and kill mosquitoes. Allan and her CMAVE cooperators are evaluating insecticides and designing innovative technology to fight biting insects and arthropods. ...

Annals of Internal Medicine tip sheet for Nov. 13, 2012

2012-11-13

1. Prophylactic Probiotics Reduce Clostridium difficile-associated Diarrhea in Patients Taking Antibiotics

Prophylactic use of probiotics can reduce Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea (CDAD). Clostridium difficile is a bacterium that can cause symptoms ranging from diarrhea to life-threatening inflammation of the colon. CDAD most commonly affects older adults in hospitals or in long term care facilities and typically occurs after use of antibiotics. Probiotics are microorganisms thought to counteract disturbances in intestinal flora, and thereby reduce the risk ...

November/December 2012 Annals of Family Medicine tip sheet

2012-11-13

52,000 More Primary Care Physicians Needed by 2025 to Meet Anticipated Demand

Researchers project the United States will need 52,000 additional primary care physicians by 2025 — a 25 percent increase in the current workforce — to address the expected increases in demand due to population growth, aging, and insurance expansion following passage of the Affordable Care Act. Analyzing nationally representative data, the researchers conclude population growth will be the single greatest driver of increased primary care utilization, requiring approximately 33,000 additional ...

Head injury + pesticide exposure = Triple the risk of Parkinson's disease

2012-11-13

MINNEAPOLIS – A new study shows that people who have had a head injury and have lived or worked near areas where the pesticide paraquat was used may be three times more likely to develop Parkinson's disease. The study is published in the November 13, 2012, print issue of Neurology®, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology. Paraquat is a herbicide commonly used on crops to control weeds. It can be deadly to humans and animals.

"While each of these two factors is associated with an increased risk of Parkinson's on their own, the combination is associated ...

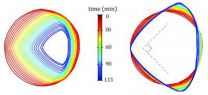

Erosion has a point -- and an edge, NYU researchers find

2012-11-13

Erosion caused by flowing water does not only smooth out objects, but can also form distinct shapes with sharp points and edges, a team of New York University researchers has found. Their findings, which appear in the latest edition of the journal the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), reveal the unexpected ways that erosion can affect landscapes and artificial materials.

The impact of erosion is widely recognized by environmentalists and geologists, but less clear is how nature's elements, notably water and air, work to shape land, rocks, and artificial ...

Saving lives could start at shift change: A simple way to improve hospital handoff conversations

2012-11-13

ANN ARBOR—At hospital shift changes, doctors and nurses exchange crucial information about the patients they're handing over—or at least they strive to. In reality, they might not spend enough time talking about the toughest cases, according to a study led by the University of Michigan.

These quick but important handoff conversations can have a major effect on patient care in the early parts of a shift. More than a half billion of them happen in U.S. hospitals every year, and that number has substantially increased with enforcement of work-hour regulations. Studies have ...