(Press-News.org) PASADENA, Calif.—In order to build the next generation of nuclear reactors, materials scientists are trying to unlock the secrets of certain materials that are radiation-damage tolerant. Now researchers at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) have brought new understanding to one of those secrets—how the interfaces between two carefully selected metals can absorb, or heal, radiation damage.

"When it comes to selecting proper structural materials for advanced nuclear reactors, it is crucial that we understand radiation damage and its effects on materials properties. And we need to study these effects on isolated small-scale features," says Julia R. Greer, an assistant professor of materials science and mechanics at Caltech. With that in mind, Greer and colleagues from Caltech, Sandia National Laboratories, UC Berkeley, and Los Alamos National Laboratory have taken a closer look at radiation-induced damage, zooming in all the way to the nanoscale—where lengths are measured in billionths of meters. Their results appear online in the journals Advanced Functional Materials and Small.

During nuclear irradiation, energetic particles like neutrons and ions displace atoms from their regular lattice sites within the metals that make up a reactor, setting off cascades of collisions that ultimately damage materials such as steel. One of the byproducts of this process is the formation of helium bubbles. Since helium does not dissolve within solid materials, it forms pressurized gas bubbles that can coalesce, making the material porous, brittle, and therefore susceptible to breakage.

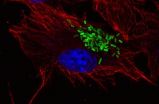

Some nano-engineered materials are able to resist such damage and may, for example, prevent helium bubbles from coalescing into larger voids. For instance, some metallic nanolaminates—materials made up of extremely thin alternating layers of different metals—are able to absorb various types of radiation-induced defects at the interfaces between the layers because of the mismatch that exists between their crystal structures.

"People have an idea, from computations, of what the interfaces as a whole may be doing, and they know from experiments what their combined global effect is. What they don't know is what exactly one individual interface is doing and what specific role the nanoscale dimensions play," says Greer. "And that's what we were able to investigate."

Peri Landau and Guo Qiang, both postdoctoral scholars in Greer's lab at the time of this study, used a chemical procedure called electroplating to either grow miniature pillars of pure copper or pillars containing exactly one interface—in which an iron crystal sits atop a copper crystal. Then, working with partners at Sandia and Los Alamos, in order to replicate the effect of helium irradiation, they implanted those nanopillars with helium ions, both directly at the interface and, in separate experiments, throughout the pillar.

The researchers then used a one-of-a-kind nanomechanical testing instrument, called the SEMentor, which is located in the subbasement of the W. M. Keck Engineering Laboratories building at Caltech, to both compress the tiny pillars and pull on them as a way to learn about the mechanical properties of the pillars—how their length changed when a certain stress was applied, and where they broke, for example.

"These experiments are very, very delicate," Landau says. "If you think about it, each one of the pillars—which are only 100 nanometers wide and about 700 nanometers long—is a thousand times thinner than a single strand of hair. We can only see them with high-resolution microscopes."

The team found that once they inserted a small amount of helium into a pillar at the interface between the iron and copper crystals, the pillar's strength increased by more than 60 percent compared to a pillar without helium. That much was expected, Landau explains, because "irradiation hardening is a well-known phenomenon in bulk materials." However, she notes, such hardening is typically linked with embrittlement, "and we do not want materials to be brittle."

Surprisingly, the researchers found that in their nanopillars, the increase in strength did not come along with embrittlement, either when the helium was implanted at the interface, or when it was distributed more broadly. Indeed, Greer and her team found, the material was able to maintain its ductility because the interface itself was able to deform gradually under stress.

This means that in a metallic nanolaminate material, small helium bubbles are able to migrate to an interface, which is never more than a few tens of nanometers away, essentially healing the material. "What we're showing is that it doesn't matter if the bubble is within the interface or uniformly distributed—the pillars don't ever fail in a catastrophic, abrupt fashion," Greer says. She notes that the implanted helium bubbles—which are described in the Advanced Functional Materials paper—were one to two nanometers in diameter; in future studies, the group will repeat the experiment with larger bubbles at higher temperatures in order to represent additional conditions related to radiation damage.

In the Small paper, the researchers showed that even nanopillars made entirely of copper, with no layering of metals, exhibited irradiation-induced hardening. That stands in stark contrast to the results from previous work by other researchers on proton-irradiated copper nanopillars, which exhibited the same strengths as those that had not been irradiated. Greer says that this points to the need to evaluate different types of irradiation-induced defects at the nanoscale, because they may not all have the same effects on materials.

While no one is likely to be building nuclear reactors out of nanopillars anytime soon, Greer argues that it is important to understand how individual interfaces and nanostructures behave. "This work is basically teaching us what gives materials the ability to heal radiation damage—what tolerances they have and how to design them," she says. That information can be incorporated into future models of material behavior that can help with the design of new materials.

INFORMATION:

Along with Greer, Landau, and Qiang, Khalid Hattar of Sandia National Laboratories is also a coauthor on the paper "The Effect of He Implantation on the Tensile Properties and Microstructure of Cu/Fe Nano-bicrystals," which appears online in Advanced Functional Materials. Peter Hosemann of UC Berkeley and Yongqiang Wang of Los Alamos National Laboratory are coauthors on the paper "Helium Implantation Effects on the Compressive Response of Cu Nanopillars," which appears online in the journal Small. The work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy and carried out, in part, in the Kavli Nanoscience Institute at Caltech.

Nano insights could lead to improved nuclear reactors

Caltech researchers examine self-healing abilities of some materials

2012-11-16

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Mixing processes could increase the impact of biofuel spills on aquatic environments

2012-11-16

Ethanol, a component of biofuel made from plants such as corn, is blended with gas in many parts of the country, but has significantly different fluid properties than pure gasoline. A group of researchers from the University of Michigan wondered how ethanol-based fuels would spread in the event of a large aquatic spill. They found that ethanol-based liquids mix actively with water, very different from how pure gasoline interacts with water and potentially more dangerous to aquatic life. The scientists will present their results, which could impact the response guidelines ...

Creating a coating of water-repellent microscopic particles to keep ice off airplanes

2012-11-16

To help planes fly safely through cold, wet, and icy conditions, a team of Japanese scientists has developed a new super water-repellent surface that can prevent ice from forming in these harsh atmospheric conditions. Unlike current inflight anti-icing techniques, the researchers envision applying this new anti-icing method to an entire aircraft like a coat of paint.

As airplanes fly through clouds of super-cooled water droplets, areas around the nose, the leading edges of the wings, and the engine cones experience low airflow, says Hirotaka Sakaue, a researcher in the ...

Visualizing floating cereal patterns to understand nanotechnology processes

2012-11-16

Small floating objects change the dynamics of the surface they are on. This is an effect every serious student of breakfast has seen as rafts of floating cereal o's arrange and rearrange themselves into patterns on the milk. Now scientists have suggested that this process may offer insight into nanoscale engineering processes.

"Small objects floating on the fluid-air interface deform the surface and attract each other through capillary interactions, a phenomenon dubbed `The Cheerios Effect,''' explains student Khoi Nguyen. "Interesting motions occur here caused by attractive ...

Study finds how bacteria inactivate immune defenses

2012-11-16

A new study by researchers at Imperial College London has identified a way in which Salmonella bacteria, which cause gastroenteritis and typhoid fever, counteract the defence mechanisms of human cells.

One way in which our cells fight off infections is by engulfing the smaller bacterial cells and then attacking them with toxic enzymes contained in small packets called lysosomes.

Published today (Thursday) in Science, the study has shown that Salmonella protects itself from this attack by depleting the supply of toxic enzymes.

Lysosomes constantly need to be replenished ...

Arthritis study reveals why gender bias is all in the genes

2012-11-16

Researchers have pieced together new genetic clues to the arthritis puzzle in a study that brings potential treatments closer to reality and could also provide insights into why more women than men succumb to the disabling condition.

Rheumatoid arthritis – which affects more than 400,000 people in the UK and about 1% of the world's population – is a complicated disease: lifestyle and environmental factors, such as smoking, diet, pregnancy and infection are thought to play a role, but it is also known that a person's genetic makeup influences their susceptibility to the ...

Uncommon features of Einstein's brain might explain his remarkable cognitive abilities

2012-11-16

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. Portions of Albert Einstein's brain have been found to be unlike those of most people and could be related to his extraordinary cognitive abilities, according to a new study led by Florida State University evolutionary anthropologist Dean Falk.

Falk, along with colleagues Frederick E. Lepore of the Robert Wood Johnson Medical School and Adrianne Noe, director of the National Museum of Health and Medicine, describe for the first time the entire cerebral cortex of Einstein's brain from an examination of 14 recently discovered photographs. The researchers ...

Study shows large-scale genomic testing feasible, impacts therapy

2012-11-16

DENVER – Targeted cancer therapy has been transforming the care of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). It is now standard practice for tumor specimens from NSCLC patients to be examined for EGFR mutations and ALK rearrangements to identify patients for therapy with EGFR and ALK inhibitors, respectively. Now, researchers say large-scale genomic testing is feasible within the clinical workflow, impacting therapeutic decisions. The study is published in the December 2012 issue of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer's (IASLC) Journal of ...

Study shows bone metastases treatment can improve overall survival

2012-11-16

DENVER – It is common for patients initially diagnosed with lung cancer to have the cancer spread to sites like the liver, brain and bone. One of the most frequent sites of metastases is the bone, with an estimated 30 to 40 percent of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) developing bone loss. A study published in the December 2012 issue of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer's (IASLC) Journal of Thoracic Oncology, shows that the bone metastases drug denosumab was associated with improved overall survival compared with zoledonic acid (ZA). ...

LLNL scientists assist in building detector to search for elusive dark matter material

2012-11-16

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory researchers are making key contributions to a physics experiment that will look for one of nature's most elusive particles, "dark matter," using a tank nearly a mile underground beneath the Black Hills of South Dakota.

The Large Underground Xenon (LUX) experiment located at the Sanford Underground Research Facility in Lead, S.D. is the most sensitive detector of its kind to look for dark matter. Thought to comprise more than 80 percent of the mass of the universe, scientists believe dark matter could hold the key to answering some ...

Study: Cellphone bans associated with fewer urban accidents

2012-11-16

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Cellphones and driving go together like knives and juggling. But when cellphone use is banned, are drivers any safer?

It depends on where you're driving, a study by University of Illinois researchers says.

The study found that, long-term, enacting a cellphone ban was associated with a relative decrease in the accident rate in urban areas. However, in very rural areas, cellphone bans were associated with higher accident rates than would otherwise be expected.

"The main idea is to use the eye test when it comes to cellphone use," says study leader ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Scientists show how to predict world’s deadly scorpion hotspots

ASU researchers to lead AAAS panel on water insecurity in the United States

ASU professor Anne Stone to present at AAAS Conference in Phoenix on ancient origins of modern disease

Proposals for exploring viruses and skin as the next experimental quantum frontiers share US$30,000 science award

ASU researchers showcase scalable tech solutions for older adults living alone with cognitive decline at AAAS 2026

Scientists identify smooth regional trends in fruit fly survival strategies

Antipathy toward snakes? Your parents likely talked you into that at an early age

Sylvester Cancer Tip Sheet for Feb. 2026

Online exposure to medical misinformation concentrated among older adults

Telehealth improves access to genetic services for adult survivors of childhood cancers

Outdated mortality benchmarks risk missing early signs of famine and delay recognizing mass starvation

Newly discovered bacterium converts carbon dioxide into chemicals using electricity

Flipping and reversing mini-proteins could improve disease treatment

Scientists reveal major hidden source of atmospheric nitrogen pollution in fragile lake basin

Biochar emerges as a powerful tool for soil carbon neutrality and climate mitigation

Tiny cell messengers show big promise for safer protein and gene delivery

AMS releases statement regarding the decision to rescind EPA’s 2009 Endangerment Finding

Parents’ alcohol and drug use influences their children’s consumption, research shows

Modular assembly of chiral nitrogen-bridged rings achieved by palladium-catalyzed diastereoselective and enantioselective cascade cyclization reactions

Promoting civic engagement

AMS Science Preview: Hurricane slowdown, school snow days

Deforestation in the Amazon raises the surface temperature by 3 °C during the dry season

Model more accurately maps the impact of frost on corn crops

How did humans develop sharp vision? Lab-grown retinas show likely answer

Sour grapes? Taste, experience of sour foods depends on individual consumer

At AAAS, professor Krystal Tsosie argues the future of science must be Indigenous-led

From the lab to the living room: Decoding Parkinson’s patients movements in the real world

Research advances in porous materials, as highlighted in the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Sally C. Morton, executive vice president of ASU Knowledge Enterprise, presents a bold and practical framework for moving research from discovery to real-world impact

Biochemical parameters in patients with diabetic nephropathy versus individuals with diabetes alone, non-diabetic nephropathy, and healthy controls

[Press-News.org] Nano insights could lead to improved nuclear reactorsCaltech researchers examine self-healing abilities of some materials