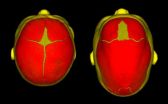

(Press-News.org) Seattle Children's Research Institute, together with an international team of scientists and clinicians from 22 other institutions, have identified two genetic risk factors for the most common form of non-syndromic craniosynostosis, a birth defect in which the bony plates of an infant's skull prematurely fuse. The condition is known as sagittal craniosynostosis and often results in an abnormal head shape and facial features.

The study identified two genes (BMP2 and BBS9) associated with sagittal craniosynostosis that are known to be involved in broader skeletal development.

Results of the research project, "A genome-wide association study identifies susceptibility loci for non-syndromic sagittal craniosynostosis near BMP2 and within BBS9," are published online today in the journal Nature Genetics.

"Seattle Children's treats hundreds of children with different types of craniosynostosis each year, many whose families are looking for answers to what causes the condition and many of whom participated in this study. This discovery brings us one step closer to unraveling the mysteries of craniosynostosis, which will lead to improved counseling of our patients and their families," said Michael Cunningham, MD, PhD, a principal investigator at Seattle Children's Research Institute who studies the genetics and developmental biology of craniosynostosis.

Dr. Cunningham is the medical director of the Craniofacial Center at Seattle Children's Hospital, Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Washington and a founding member of the International Craniosynostosis Consortium (ICC), the organization that enrolled and evaluated all study participants.

In this study – believed to be the first genome-wide association study of non-syndromic sagittal craniosynostosis – investigators scanned the whole genome of a group of children and adults with the condition and compared them to a control group without it. Researchers identified single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that were associated with the condition. SNPs are changes in DNA in which a nucleotide differs from the one normally in that position and can be used to identify genes linked to the disease.

The research team evaluated DNA, taken from blood or oral samples, of 214 cases and both of their parents, who did not have the condition. The final analysis came from a group of 130 children and their families.

During normal development, the bony plates of the skull are separate during fetal development and early infancy, which allows for growth of the skull. The borders where these bony plates intersect are known as sutures. The sagittal suture usually does not fuse until adulthood. If the midline suture at the top of the head closes too early, a child will develop sagittal craniosynostosis. Without surgical treatment, this can cause increased pressure within the skull, visual problems and learning disabilities.

Sagittal craniosynostosis affects about one in 5,000 newborns and boys are three to four times more likely than girls to have the condition. Prior research has suggested that the condition can recur in families, but the exact genetic causes have not been well understood.

"Our participation in this collaborative effort and our ongoing research into the biology of craniosynostosis will result in tangible changes in how we diagnose and treat craniosynostosis," Dr. Cunningham said.

INFORMATION:

Simon Boyadjiev, Professor of Pediatrics and Genetics at UC Davis, is the founder of the ICC and principal investigator of this study. Other study authors include:; Cristina M. Justice, Yoonhee Kim and Alexander F. Wilson of the U.S. National Human Genome Research Institute; Garima Yagnik, Craig Senders, James Boggan, Marike Zwienenberg-Lee, and Jinoh Kim of UC Davis School of Medicine; Inga Peter, Ethylin Wang Jabs, Monica Erazo, Xiaoqian Ye, Edmond Ainehsazan, Lisong Shi and Peter J. Taub of Mount Sinai School of Medicine; Virginia Kimonis of UC Irvine School of Medicine; Tony Roscioli of University of New South Wales, Australia; Steven A. Wall and Andrew O.M. Wilkie, John Radcliffe Hospital, United Kingdom; Joan Stoler of Children's Hospital Boston; Joan T. Richtsmeier and Yann Heuzé of Pennsylvania State University; Pedro A. Sanchez-Lara of University of Southern California; Michael F. Buckley of SEALS, Australia; Charlotte M. Druschel, Michele Caggana and Denise M. Kay of New York State Department of Health; James L. Mills of Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; Paul A. Romitti of University of Iowa; Ophir D. Klein of UC San Francisco School of Medicine and Cyrill Naydenov of the Medical University, Sofia, Bulgaria.

The research was supported by grants to the various authors from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (National Institutes of Health ,NIH) and National Center for Research Resources (NIH); the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; the Intramural Research Program of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH); the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NIH); the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; the University of Southern California Child Health Research Career Development Program and the UCLA Child Health Research Career Development Program; the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act; the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; the National Human Genome Research Institute (NIH) and a contract from the NIH to the Johns Hopkins University.

About Seattle Children's Research Institute

Located in downtown Seattle's biotech corridor, Seattle Children's Research Institute is pushing the boundaries of medical research to find cures for pediatric diseases and improve outcomes for children all over the world. Internationally recognized investigators and staff at the research institute are advancing new discoveries in cancer, genetics, immunology, pathology, infectious disease, injury prevention and bioethics, among others. As part of Seattle Children's Hospital, the research institute brings together leading minds in pediatric research to provide patients with the best care possible. Seattle Children's serves as the primary teaching, clinical and research site for the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Washington School of Medicine, which consistently ranks as one of the best pediatric departments in the country. For more information, visit http://www.seattlechildrens.org/research.

Seattle Children's Research Institute helps identify causes of sagittal craniosynostosis

2012-11-20

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Martian history: Finding a common denominator with Earth's

2012-11-20

Washington, DC — A team of scientists, including Carnegie's Conel Alexander and Jianhua Wang, studied the hydrogen in water from the Martian interior and found that Mars formed from similar building blocks to that of Earth, but that there were differences in the later evolution of the two planets. This implies that terrestrial planets, including Earth, have similar water sources--chondritic meteorites. However, unlike on Earth, Martian rocks that contain atmospheric volatiles such as water, do not get recycled into the planet's deep interior. Their work will be published ...

Faulty development of immature brain cells causes hydrocephalus

2012-11-20

Researchers at the University of Iowa have discovered a new cause of hydrocephalus, a devastating neurological disorder that affects between one and three of every 1,000 babies born. Working in mice, the researchers identified a cell signaling defect, which disrupts immature brain cells involved in normal brain development. By bypassing the defect with a drug treatment, the team was able to correct one aspect of the cells' development and reduce the severity of the hydrocephalus. The findings were published online Nov. 18 in the journal Nature Medicine.

"Our findings ...

CCNY landscape architect offers storm surge defense alternatives

2012-11-20

The flooding in New York and New Jersey caused by Superstorm Sandy prompted calls from Gov. Andrew Cuomo and other officials to consider building storm surge barriers to protect Lower Manhattan from future catastrophes. But, such a strategy could make things even worse for outlying areas that were hit hard by the hurricane, such as Staten Island, the New Jersey Shore and Long Island's South Shore, a City College of New York landscape architecture professor warns.

"If you mitigate to protect Lower Manhattan, you increase the impact in other areas," says Catherine Seavitt ...

New tumor tracking technique may improve outcomes for lung cancer patients

2012-11-20

PHILADELPHIA— Medical physicists at Thomas Jefferson University and Jefferson's Kimmel Cancer Center are one step closer to bringing a new tumor-tracking technique into the clinic that delivers higher levels of radiation to moving tumors, while sparing healthy tissue in lung cancer patients.

Evidence has shown a survival advantage for lung cancer patients treated with higher doses of radiation. Therefore, there is an increased interest to find novel ways to better track tumors—which are in constant motion because of breathing—in order to up the dosage during radiation ...

Multiple sclerosis 'immune exchange' between brain and blood is uncovered

2012-11-20

DNA sequences obtained from a handful of patients with multiple sclerosis at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Medical Center have revealed the existence of an "immune exchange" that allows the disease-causing cells to move in and out of the brain.

The cells in question, obtained from spinal fluid and blood samples, are called B cells, which normally help to clear foreign infections from the body but sometimes react strongly with the body itself. One of the current theories of multiple sclerosis, which strikes hundreds of thousands of Americans and millions ...

Comments, traffic statistics help empower bloggers

2012-11-20

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- Whether bloggers are writing to change the world, or just discussing a bad break-up, they may get an extra boost of motivation from traffic-measuring and interactive tools that help them feel more connected to and more influential in their communities, according to researchers.

In a series of studies, female bloggers showed that they enjoyed blogging because it made them feel empowered and part of a community, said Carmen Stavrositu, who recently completed doctoral work in mass communications at Penn State. The studies also indicated that the sheer ...

Failed explosions explain most peculiar supernovae

2012-11-20

Supercomputer simulations have revealed that a type of oddly dim, exploding star is probably a class of duds—one that could nonetheless throw new light on the mysterious nature of dark energy.

Most of the thousands of exploding stars classified as type Ia supernovae look similar, which is why astrophysicists use them as accurate cosmic distance indicators. They have shown that the expansion of the universe is accelerating under the influence of an unknown force now called dark energy; yet approximately 20 type Ia supernovae look peculiar.

"They're all a little bit ...

Scripps Research Institute team identifies a potential cause of Parkinson's disease

2012-11-20

LA JOLLA, CA – November 19, 2012 – Deciphering what causes the brain cell degeneration of Parkinson's disease has remained a perplexing challenge for scientists. But a team led by scientists from The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) has pinpointed a key factor controlling damage to brain cells in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. The discovery could lead to new targets for Parkinson's that may be useful in preventing the actual condition.

The team, led by TSRI neuroscientist Bruno Conti, describes the work in a paper published online ahead of print on November 19, ...

Astronomers pin down origins of 'mile markers' for expansion of universe

2012-11-20

COLUMBUS, Ohio – A study using a unique new instrument on the world's largest optical telescope has revealed the likely origins of especially bright supernovae that astronomers use as easy-to-spot "mile markers" to measure the expansion and acceleration of the universe.

In a paper to appear in the Astrophysical Journal, researchers describe observations of recent supernova 2011fe that they captured with the Large Binocular Telescope (LBT) using a tool created at Ohio State University: the Multi-Object Double Spectrograph (MODS).

MODS measures the frequencies and intensities ...

Smoking in pregnancy tied to lower reading scores

2012-11-20

Yale School of Medicine researchers have found that children born to mothers who smoked more than one pack per day during pregnancy struggled on tests designed to measure how accurately a child reads aloud and comprehends what they read.

The findings are published in the current issue of The Journal of Pediatrics.

Lead author Jeffrey Gruen, M.D., professor of pediatrics and genetics at Yale School of Medicine, and colleagues analyzed data from more than 5,000 children involved in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC), a large-scale study of ...