Saving water without hurting peach production

2012-11-21

(Press-News.org) U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) scientists are helping peach growers make the most of dwindling water supplies in California's San Joaquin Valley.

Agricultural Research Service (ARS) scientist James E. Ayars at the San Joaquin Valley Agricultural Sciences Center in Parlier, Calif., has found a way to reduce the amount of water given post-harvest to early-season peaches so that the reduction has a minimal effect on yield and fruit quality. ARS is USDA's principal intramural scientific research agency, and the research supports the USDA priority of promoting international food security.

The valley has about 25,000 acres of peach orchards that must be irrigated throughout the summer. Early-season peaches are normally harvested in May, but require most of their water from June through September, a time when temperatures and demands for water are at their highest. Snow packs in the Sierra Nevada have traditionally been a sufficient water source for growers, but earlier snowmelts have made water more precious with each summer. Wells that supply the valley have had to reach deeper to meet increasing demands.

Ayars and ARS scientist Dong Wang, also based at Parlier, irrigated a 4-acre plot of early-season peach trees from March to the May harvest. From June to September, they gave the trees either 25 percent of the amount of water they'd normally receive, 50 percent of the normal amount, or 100 percent. The scientists measured soil water content once a week to be sure that even with periodic rainfall, trees were given appropriate deficit-irrigation treatments. They also used three types of irrigation systems: microspray, subsurface drip irrigation, and furrow irrigation, in which water is distributed in shallow canal-like rows near the trees. Defective fruit were counted and removed after each harvest.

The results showed that reducing post-harvest irrigation levels to 25 percent of the normal amount had negative effects on yield and fruit quality, but that giving 50 percent less water than normal had minimal effects on the following year's quality and yield. The subsurface drip irrigation systems tended to have the lowest yields within a given year, but differences were generally not statistically significant. The researchers also found that trees needed less pruning and maintenance because the deficit irrigation slowed plant growth.

###

Read more about this research in the November/December 2012 issue of Agricultural Research magazine.

http://www.ars.usda.gov/is/AR/archive/nov12/peach1112.htm

USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. To file a complaint of discrimination, write: USDA, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights, Office of Adjudication, 1400 Independence Ave., SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call 866-632-9992 (Toll-free Customer Service), 800-877-8339 (Local or Federal relay), 866-377-8642 (Relay voice users).

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2012-11-21

Forging dies must withstand a lot. They must be hard so that their surface does not get too worn out and is able to last through great changes in temperature and handle the impactful blows of the forge. However, the harder a material is, the more brittle it becomes - and forging dies are less able to handle the stress from the impact. For this reason, the manufacturers had to find a compromise between hardness and strength. One of the possibilities is to surround a semi-hard, strong material with a hard layer. The problem is that the layer rests on the softer material and ...

2012-11-21

The age-adjusted prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) varies considerably within the United States, from less than 4 percent of the population in Washington and Minnesota to more than 9 percent in Alabama and Kentucky. These state-level rates are among the COPD data available for the first time as part of the newly released 2011 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey.

"COPD is a tremendous public health burden and a leading cause of death. It is a health condition that needs to be urgently addressed, particularly on a local level," ...

2012-11-21

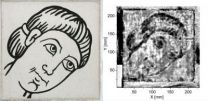

It was a special moment for Michael Panzner of the Fraunhofer Institute for Material and Beam Technology IWS in Dresden, Germany and his partners: in the Dresden Hygiene Museum the scientists were examining a wall picture by Gerhard Richter that had been believed lost long ago. Shortly before leaving the German Democratic Republic the artist had left it behind as a journeyman's project. Then, in the 1960s, it was unceremoniously painted over. However, instead of being interested in the picture, Panzer was far more interested in the new detector which was being used for ...

2012-11-21

HOUSTON – (Nov. 22, 2012) – Using a new technique called cryo-electron tomography, two research teams at Baylor College of Medicine (www.bcm.edu) have created a three-dimensional map that gives a better understanding of how the architecture of the rod sensory cilium (part of one type of photoreceptor in the eye) is changed by genetic mutation and how that affects its ability to transport proteins as part of the light-sensing process.

Almost all mammalian cells have cilia. Some are motile and some are not. They play a central role in cellular operations, and when they ...

2012-11-21

Academics at the Universities of Bristol, Yale and Calgary have shown that prehistoric birds had a much more primitive version of the wings we see today, with rigid layers of feathers acting as simple airfoils for gliding.

Close examination of the earliest theropod dinosaurs suggests that feathers were initially developed for insulation, arranged in multiple layers to preserve heat, before their shape evolved for display and camouflage.

As evolution changed the configuration of the feathers, their important role in the aerodynamics and mechanics of flight became more ...

2012-11-21

ADELPHI, Md. – A new center that combines advanced computing resources at the University of Maryland, College Park (UMD) with clinical data and biomedical expertise at the University of Maryland, Baltimore (UMB) could soon revolutionize the efficiency and effectiveness of health care in the state of Maryland and beyond.

The Center for Health-related Informatics and Bioimaging (CHIB) announced today joins computer scientists, life scientists, engineers, physicists, biostatisticians and others at the College Park campus with imaging specialists, physicians, clinicians ...

2012-11-21

By examining art printed from woodblocks spanning five centuries, Blair Hedges, a professor of biology at Penn State University, has identified the species responsible for making the ever-present wormholes in European printed art since the Renaissance. The hole-makers, two species of wood-boring beetles, are widely distributed today, but the "wormhole record," as Hedges calls it, reveals a different pattern in the past, where the two species met along a zone across central Europe like a battle line of two armies. The research, which is the first of its kind to use printed ...

2012-11-21

In the 1960s and 1970s, classic social psychological studies were conducted that provided evidence that even normal, decent people can engage in acts of extreme cruelty when instructed to do so by others. However, in an essay published November 20 in the open access journal PLOS Biology, Professors Alex Haslam and Stephen Reicher revisit these studies' conclusions and explain how awful acts involve not just obedience, but enthusiasm too—challenging the long-held belief that human beings are 'programmed' for conformity.

This belief can be traced back to two landmark empirical ...

2012-11-21

Animals, including humans, actively select the gut microbes that are the best partners and nurture them with nutritious secretions, suggests a new study led by Oxford University, and published November 20 in the open-access journal PLOS Biology.

The Oxford team created an evolutionary computer model of interactions between gut microbes and the lining (the host epithelial cell layer) of the animal gut. The model shows that beneficial microbes that are slow-growing are rapidly lost, and need to be helped by host secretions, such as specific nutrients, that favour the beneficial ...

2012-11-21

A new study published November 20 in the open-access journal PLOS Biology has identified hundreds of small regions of the genome that appear to be uniquely regulated in human neurons. These regulatory differences distinguish us from other primates, including monkeys and apes, and as neurons are at the core of our unique cognitive abilities, these features may ultimately hold the key to our intellectual prowess (and also to our potential vulnerability to a wide range of 'human-specific' diseases from autism to Alzheimer's).

Exploring which features in the genome separate ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Saving water without hurting peach production