(Press-News.org) HOUSTON – (Dec. 3, 2012) – Researchers at Rice University have found a way to kill some diseased cells and treat others in the same sample at the same time. The process activated by a pulse of laser light leaves neighboring healthy cells untouched.

The unique use for tunable plasmonic nanobubbles developed in the Rice lab of Dmitri Lapotko shows promise to replace several difficult processes now used to treat cancer patients, among others, with a fast, simple, multifunctional procedure.

The research is the focus of a paper published online this week by the American Chemical Society journal ACS Nano and was carried out at Rice by biochemist Lapotko, research scientist and lead author Ekaterina Lukianova-Hleb and undergraduate student Martin Mutonga, with assistance from the Center for Cell and Gene Therapy at Baylor College of Medicine (BCM), Texas Children's Hospital and the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Plasmonic nanobubbles that are 10,000 times smaller than a human hair cause tiny explosions. The bubbles form around plasmonic gold nanoparticles that heat up when excited by an outside energy source – in this case, a short laser pulse – and vaporize a thin layer of liquid near the particle's surface. The vapor bubble quickly expands and collapses. Lapotko and his colleagues had already found that plasmonic nanobubbles kill cancer cells by literally exploding them without damage to healthy neighbors, a process that showed much higher precision and selectivity compared with those mediated by gold nanoparticles alone, he said.

The new project takes that remarkable ability a few steps further. A series of experiments proved a single laser pulse creates large plasmonic nanobubbles around hollow gold nanoshells, and these large nanobubbles selectively destroy unwanted cells. The same laser pulse creates smaller nanobubbles around solid gold nanospheres that punch a tiny, temporary pore in the wall of a cell and create an inbound nanojet that rapidly "injects" drugs or genes into the other cells.

In their experiments, Lapotko and his team placed 60-nanometer-wide hollow nanoshells in model cancer cells and stained them red. In a separate batch, they put 60-nanometer-wide nanospheres into the same type of cells and stained them blue.

After suspending the cells together in a green fluorescent dye, they fired a single wide laser pulse at the combined sample, washed the green stain out and checked the cells under a microscope. The red cells with the hollow shells were blasted apart by large plasmonic nanobubbles. The blue cells were intact, but green-stained liquid from outside had been pulled into the cells where smaller plasmonic nanobubbles around the solid spheres temporarily pried open the walls.

Because all of this happens in a fraction of a second, as many as 10 billion cells per minute could be selectively processed in a flow-through system like that under development at Rice, said Lapotko, a faculty fellow in biochemistry and cell biology and in physics and astronomy. That has potential to advance cell and gene therapy and bone marrow transplantation, he said.

Most disease-fighting and gene therapies require "ex vivo" – outside the body – processing of human cell grafts to eliminate unwanted (like cancerous) cells and to genetically modify other cells to increase their therapeutic efficiency, Lapotko said. "Current cell processing is often slow, expensive and labor intensive and suffers from high cell losses and poor selectivity. Ideally both elimination and transfection (the introduction of materials into cells) should be highly efficient, selective, fast and safe."

Plasmonic nanobubble technology promises "a method of doing multiple things to a cell population at the same time," said Malcolm Brenner, a professor of medicine and of pediatrics at BCM and director of BCM's Center for Cell and Gene Therapy, who collaborates with the Rice team. "For example, if I want to put something into a stem cell to make it turn into another type of cell, and at the same time kill surrounding cells that have the potential to do harm when they go back into a patient -- or into another patient -- these very tunable plasmonic nanobubbles have the potential to do that."

The long-term objective of a collaborative effort among Rice, BCM, Texas Children's Hospital and MD Anderson is to improve the outcome for patients with diseases whose treatment requires ex vivo cell processing, Lapotko said.

Lapotko plans to build a prototype of the technology with an eye toward testing with human cells in the near future. "We'd like for this to be a universal platform for cell and gene therapy and for stem cell transplantation," he said.

INFORMATION:

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health.

Read the abstract at http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/nn3045243

This news release can be found online at news.rice.edu.

Follow Rice News and Media Relations via Twitter @RiceUNews

Related Materials:

The Plasmonic Nanobubble Lab at Rice: http://pnblab.blogs.rice.edu

Images for download:

http://news.rice.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/NANOBUBBLES-7-WEB.jpg

Identical cells stained red and blue were the target of research at Rice University to show the effect of plasmonic nanobubbles. The bubbles form around heated gold nanoparticles that target particular cells, like cancer cells. When the particles are hollow, bubbles form that are large enough to kill the cell when they burst. When the particles are solid, the bubbles are smaller and can punch a temporary hole in a cell wall, allowing drugs or other material to flow in. Both effects can be achieved simultaneously with a single laser pulse. (Credit: Plasmonic Nanobubble Lab/Rice University)

http://news.rice.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/NANOBUBBLES-8-WEB.jpg

After the laser pulse, red-stained cells show evidence of massive damage from exploding nanobubbles, while blue-stained cells remained intact, but with green fluorescent dye pulled in from the outside. (Credit: Plasmonic Nanobubble Lab/Rice University)

http://news.rice.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/NANOBUBBLES-3-WEB.jpg

Researchers at Rice University have found a way to make multi-functional use of plasmonic nanobubbles in the treatment of disease. From left: Research scientist Ekaterina Lukianova-Hleb, Rice senior Martin Mutonga and Professor Dmitri Lapotko. (Credit: Jeff Fitlow/Rice University)

http://news.rice.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/NANOBUBBLES-4-WEB.jpg

Rice University research scientist Ekaterina Lukianova-Hleb, lead author of a new ACS Nano paper, adjusts equipment used to determine that a single laser blast can selectively kill or modify cells in a single sample through the manipulation of plasmonic nanobubbles. (Credit: Jeff Fitlow/Rice University)

Multitasking plasmonic nanobubbles kill some cells, modify others

Rice University discovery could simplify and improve difficult processes used to treat diseases, including cancer

2012-12-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Listen up, doc: Empathy raises patients' pain tolerance

2012-12-04

A doctor-patient relationship built on trust and empathy doesn't just put patients at ease – it actually changes the brain's response to stress and increases pain tolerance, according to new findings from a Michigan State University research team.

Medical researchers have shown in recent studies that doctors who listen carefully have happier patients with better health outcomes, but the underlying mechanism was unknown, said Issidoros Sarinopoulos, professor of radiology at MSU.

"This is the first study that has looked at the patient-centered relationship from a neurobiological ...

Women with sleep apnea have higher degree of brain damage than men, UCLA study shows

2012-12-04

Women suffering from sleep apnea have, on the whole, a higher degree of brain damage than men with the disorder, according to a first-of-its-kind study conducted by researchers at the UCLA School of Nursing. The findings are reported in the December issue of the peer-reviewed journal SLEEP.

Obstructive sleep apnea is a serious disorder that occurs when a person's breathing is repeatedly interrupted during sleep, sometimes hundreds of times. Each time, the oxygen level in the blood drops, eventually resulting in damage to many cells in the body. If left untreated, it ...

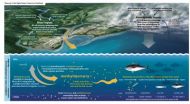

Mercury releases contaminate ocean fish: Dartmouth-led effort publishes major findings

2012-12-04

In new research published in a special issue of the journal Environmental Health Perspectives and in "Sources to Seafood: Mercury Pollution in the Marine Environment"— a companion report by the Dartmouth-led Coastal and Marine Mercury Ecosystem Research Collaborative (C-MERC), scientists report that mercury released into the air and then deposited into oceans contaminates seafood commonly eaten by people in the U.S. and globally.

Over the past century, mercury pollution in the surface ocean has more than doubled, as a result of past and present human activities such ...

Baby's health is tied to mother's value for family

2012-12-04

The value that an expectant mother places on family—regardless of the reality of her own family situation—predicts the birthweight of her baby and whether the child will develop asthma symptoms three years later, according to new research from USC.

The findings suggest that one's culture is a resource that can provide tangible physical health benefits.

"We know that social support has profound health implications; yet, in this case, this is more a story of beliefs than of actual family support," said Cleopatra Abdou, assistant professor at the USC Davis School of Gerontology.

Abdou ...

University of Minnesota researchers find new target for Alzheimer's drug development

2012-12-04

MINNEAPOLIS/ST. PAUL (December 3, 2012) – Researchers at the University of Minnesota's Center for Drug Design have developed a synthetic compound that, in a mouse model, successfully prevents the neurodegeneration associated with Alzheimer's disease.

In the pre-clinical study, researchers Robert Vince, Ph.D.; Swati More, Ph.D.; and Ashish Vartak, Ph.D., of the University's Center for Drug Design, found evidence that a lab-made compound known as psi-GSH enables the brain to use its own protective enzyme system, called glyoxalase, against the Alzheimer's disease process. ...

Western University researchers make breakthrough in arthritis research

2012-12-04

Researchers at Western University have made a breakthrough that could lead to a better understanding of a common form of arthritis that, until now, has eluded scientists.

According to The Arthritis Society, the second most common form of arthritis after osteoarthritis is "diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis" or DISH. It affects between six and 12 percent of North Americans, usually people older than 50. DISH is classified as a form of degenerative arthritis and is characterized by the formation of excessive mineral deposits along the sides of the vertebrae in the ...

New Jamaica butterfly species emphasizes need for biodiversity research

2012-12-04

GAINESVILLE, Fla. — University of Florida scientists have co-authored a study describing a new Lepidoptera species found in Jamaica's last remaining wilderness.

Belonging to the family of skipper butterflies, the new genus and species is the first butterfly discovered in Jamaica since 1995. Scientists hope the native butterfly will encourage conservation of the country's last wilderness where it was discovered: the Cockpit Country. The study appearing in today's Tropical Lepidoptera Research, a bi-annual print journal, underscores the need for further biodiversity research ...

Managing care and competition

2012-12-04

Medicare Advantage (MA), with more than 10 million enrollees, is the largest alternative to traditional Medicare. MA's managed care approach was designed to provide coordinated, integrated care for patients and savings for taxpayers, but since the program launched as Medicare Part C in 1985, critics have said that the system limited enrollee freedom of choice without significant benefit or savings to the Medicare program. They also pointed to the tendency of some private payers to design benefit plans and marketing campaigns that attracted healthier patients, leaving sicker, ...

New study shows probiotics help fish grow up faster and healthier

2012-12-04

BALTIMORE, MD (December 3, 2012)— Probiotics like those found in yogurt are not only good for people--they are also good for fish. A new study by scientists at the Institute of Marine and Environmental Technology found that feeding probiotics to baby zebrafish accelerated their development and increased their chances of survival into adulthood.

This research could help increase the success of raising rare ornamental fish to adulthood. It also has implications for aquaculture, since accelerating the development of fish larvae--the toughest time for survival--could mean ...

Ames Laboratory scientists develop indium-free organic light-emitting diodes

2012-12-04

Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Ames Laboratory have discovered new ways of using a well-known polymer in organic light emitting diodes (OLEDs), which could eliminate the need for an increasingly problematic and breakable metal-oxide used in screen displays in computers, televisions, and cell phones.

The metal-oxide, indium tin oxide (ITO), is a transparent conductor used as the anode for flat screen displays, and has been the standard for decades. Due to indium's limited supply, increasing cost and the increasing demand for its use in screen and lighting ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

How rice plants tell head from toe during early growth

Scientists design solar-responsive biochar that accelerates environmental cleanup

Construction of a localized immune niche via supramolecular hydrogel vaccine to elicit durable and enhanced immunity against infectious diseases

Deep learning-based discovery of tetrahydrocarbazoles as broad-spectrum antitumor agents and click-activated strategy for targeted cancer therapy

DHL-11, a novel prieurianin-type limonoid isolated from Munronia henryi, targeting IMPDH2 to inhibit triple-negative breast cancer

Discovery of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro inhibitors and RIPK1 inhibitors with synergistic antiviral efficacy in a mouse COVID-19 model

Neg-entropy is the true drug target for chronic diseases

Oxygen-boosted dual-section microneedle patch for enhanced drug penetration and improved photodynamic and anti-inflammatory therapy in psoriasis

Early TB treatment reduced deaths from sepsis among people with HIV

Palmitoylation of Tfr1 enhances platelet ferroptosis and liver injury in heat stroke

Structure-guided design of picomolar-level macrocyclic TRPC5 channel inhibitors with antidepressant activity

Therapeutic drug monitoring of biologics in inflammatory bowel disease: An evidence-based multidisciplinary guidelines

New global review reveals integrating finance, technology, and governance is key to equitable climate action

New study reveals cyanobacteria may help spread antibiotic resistance in estuarine ecosystems

Around the world, children’s cooperative behaviors and norms converge toward community-specific norms in middle childhood, Boston College researchers report

How cultural norms shape childhood development

University of Phoenix research finds AI-integrated coursework strengthens student learning and career skills

Next generation genetics technology developed to counter the rise of antibiotic resistance

Ochsner Health hospitals named Best-in-State 2026

A new window into hemodialysis: How optical sensors could make treatment safer

High-dose therapy had lasting benefits for infants with stroke before or soon after birth

‘Energy efficiency’ key to mountain birds adapting to changing environmental conditions

Scientists now know why ovarian cancer spreads so rapidly in the abdomen

USF Health launches nation’s first fully integrated institute for voice, hearing and swallowing care and research

Why rethinking wellness could help students and teachers thrive

Seabirds ingest large quantities of pollutants, some of which have been banned for decades

When Earth’s magnetic field took its time flipping

Americans prefer to screen for cervical cancer in-clinic vs. at home

Rice lab to help develop bioprinted kidneys as part of ARPA-H PRINT program award

Researchers discover ABCA1 protein’s role in releasing molecular brakes on solid tumor immunotherapy

[Press-News.org] Multitasking plasmonic nanobubbles kill some cells, modify othersRice University discovery could simplify and improve difficult processes used to treat diseases, including cancer