(Press-News.org) Highlanders in Tibet and Ethiopia share a biological adaptation that enables them to thrive in the low oxygen of high altitudes, but the ability to pass on the trait appears to be linked to different genes in the two groups, research from a Case Western Reserve University scientist and colleagues shows.

The adaptation is the ability to maintain a relatively low (for high altitudes) level of hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying protein in red blood cells. Members of ethnic populations - such as most Americans - who historically live at low altitudes naturally respond to the thin air by increasing hemoglobin levels. The response can help draw oxygen into the body, but increases blood viscosity and the risks for thrombosis, stroke and difficulties with pregnancies.

By revealing how populations can live in severe environments, the research may provide insight for managing high-altitude sickness and for treating low blood-oxygen conditions such as asthma, sleep apnea, and heart problems among all people.

How long such physiological and genetic changes take remains a question. The researchers found the adaptation in an ethnic group that has lived high in mountains of Ethiopia for at least 5,000 years, but not among a related group that has lived high in the mountains for 500 years.

The findings are reported today in the open-access online journal PLoS Genetics.

In their first comparison, the researchers found that the genes responsible for hemoglobin levels in Tibetans don't influence an ethnic group called the Amhara

The Amhara have lived more than a mile high in the Semien Mountains of northern Ethiopia for 5,000 to 70,000 years. A different variant on the Amhara genome, far away from the location of the Tibetan variant, is significantly associated with their low hemoglobin levels.

"All indications are we're seeing convergent evolution," said Cynthia Beall, professor of anthropology at Case Western Reserve University and one of the leaders of the study. Convergent evolution is when two separate populations change biologically in a similar way to adapt to a similar environment yet use different mechanisms.

"These were two different evolutionary experiments," Beall said of the mountain dwellers in Tibet and Ethiopia. "On one level—the biological response—they are the same. On another level—the changes in the gene pool—they are different."

Beall investigated the adaptations and genetic links with Gorka Alkorta-Aranburu, David Witonsky, Jonathan K. Pritchard and Anna Di Rienzo, of the University of Chicago department of human genetics, and Amha Gebremedhin of Adis Ababa University's department of internal medicine in Ethiopia.

In addition to studying the Amhara, the researchers looked for changes in physiology and genetics among a related ethnic group, the Oromo, who have lived more than a mile above sea level in the Bale Mountains of southern Ethiopia for 500 years.

They found no long-term adaptation and no genetic changes related to a low-oxygen environment.

They found the Omoro had high levels of hemoglobin, as would be expected for a lowland population.

Using the same samples collected from the Amhara and Oromo, the researchers are now studying biological traits among the groups, including ventilation, and the influence of vasoconstrictors and vasodilators on blood flow, and searching for associations with genes.

They also plan to continue research and study blood flow, especially through the heart and lungs of the highlanders, and to test the metabolic rate of mitochondria that use oxygen to create the energy on which our cells and we operate.

"We also want to find whether people with the variants for low hemoglobin levels have more children and a higher survival rate," Beall said. "That's the evolutionary payoff."

### END

Different genes behind same adaptation to thin air

Apparent example of convergent human evolution on 2 continents

2012-12-07

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Deception can be perfected

2012-12-07

EVANSTON, Ill. --- With a little practice, one could learn to tell a lie that may be indistinguishable from the truth.

New Northwestern University research shows that lying is more malleable than previously thought, and with a certain amount of training and instruction, the art of deception can be perfected.

People generally take longer and make more mistakes when telling lies than telling the truth, because they are holding two conflicting answers in mind and suppressing the honest response, previous research has shown. Consequently, researchers in the present study ...

Gladstone scientists discover novel mechanism by which calorie restriction influences longevity

2012-12-07

SAN FRANCISCO, CA—December 6, 2012—Scientists at the Gladstone Institutes have identified a novel mechanism by which a type of low-carb, low-calorie diet—called a "ketogenic diet"—could delay the effects of aging. This fundamental discovery reveals how such a diet could slow the aging process and may one day allow scientists to better treat or prevent age-related diseases, including heart disease, Alzheimer's disease and many forms of cancer.

As the aging population continues to grow, age-related illnesses have become increasingly common. Already in the United States, ...

Attitudes predict ability to follow post-treatment advice

2012-12-07

SAN ANTONIO, TX (December 6, 2012)—Women are more likely to follow experts' advice on how to reduce their risk of an important side effect of breast cancer surgery—like lymphedema—if they feel confident in their abilities and know how to manage stress, according to new research from Fox Chase Cancer Center to be presented at the 2012 CTRC-AACR San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium on Saturday, December 8, 2012.

These findings suggest that clinicians must do more than just inform women of the ways they should change their behavior, says Suzanne M. Miller, PhD, Professor ...

Seeing in color at the nanoscale

2012-12-07

If nanoscience were television, we'd be in the 1950s. Although scientists can make and manipulate nanoscale objects with increasingly awesome control, they are limited to black-and-white imagery for examining those objects. Information about nanoscale chemistry and interactions with light—the atomic-microscopy equivalent to color—is tantalizingly out of reach to all but the most persistent researchers.

But that may all change with the introduction of a new microscopy tool from researchers at the Department of Energy (DOE)'s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley ...

Notre Dame research reveals migrating Great Lakes salmon carry contaminants upstream

2012-12-07

Be careful what you eat, says University of Notre Dame stream ecologist Gary Lamberti.

If you're catching and eating fish from a Lake Michigan tributary with a strong salmon run, the stream fish — brook trout, brown trout, panfish — may be contaminated by pollutants carried in by the salmon.

Research by Lamberti, professor and chair of biology, and his laboratory has revealed that salmon, as they travel upstream to spawn and die, carry industrial pollutants into Great Lakes streams and tributaries. The research was recently published in the journal Environmental Science ...

Silver nanocubes make super light absorbers

2012-12-07

DURHAM, N.C. -- Microscopic metallic cubes could unleash the enormous potential of metamaterials to absorb light, leading to more efficient and cost-effective large-area absorbers for sensors or solar cells, Duke University researchers have found.

Metamaterials are man-made materials that have properties often absent in natural materials. They are constructed to provide exquisite control over the properties of waves, such as light. Creating these materials for visible light is still a technological challenge that has traditionally been achieved by lithography, in which ...

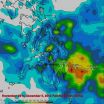

NASA compiles Typhoon Bopha's Philippines Rainfall totals from space

2012-12-07

NASA's Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission, or TRMM satellite can estimate rainfall rates from its orbit in space, and its data is also used to compile estimated rainfall totals. NASA just released an image showing those rainfall totals over the Philippines, where severe flooding killed several hundred people. Bopha is now a tropical storm in the South China Sea.

High winds, flooding and landslides from heavy rains with Typhoon Bopha have caused close to 300 deaths in the southern Philippines.

The TRMM satellite's primary mission is the measurement of rainfall in the ...

UC Davis study shows that treadmill testing can predict heart disease in women

2012-12-07

(SACRAMENTO, Calif.) — Although there is a widespread belief among physicians that the exercise treadmill test (ETT) is not reliable in evaluating the heart health of women, UC Davis researchers have found that the test can accurately predict coronary artery disease in women over the age of 65. They also found that two specific electrocardiogram (EKG) indicators of heart stress during an ETT further enhanced its predictive power.

Published in the December issue of The American Journal of Cardiology, the study can help guide cardiologists in making the treadmill test ...

TGen-US Oncology data guides treatment of metastatic triple-negative breast cancer patients

2012-12-07

PHOENIX, Ariz. — Dec. 6, 2012 — Genomic sequencing has revealed therapeutic drug targets for difficult-to-treat, metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), according to an unprecedented study by the Translational Genomic Research Institute (TGen) and US Oncology Research.

The study is published by the journal Molecular Cancer Therapeutics and is currently available online.

By sequencing, or spelling out, the billions of letters contained in the genomes of 14 tumors from ethnically diverse metastatic TNBC patients, TGen and US Oncology Research investigators found ...

General thoracic surgeons emerge as leading providers of complex, noncardiac thoracic surgery

2012-12-07

While thoracic surgeons are traditionally known as the experts who perform heart surgeries, a UC Davis study has found that general thoracic surgeons, especially those at academic health centers, perform the vast majority of complex noncardiac operations, including surgeries of the esophagus and lungs.

The authors said their results, published in the October issue of The Annals of Thoracic Surgery, support the designation of general thoracic surgery as a distinct specialty, which will benefit patients when selecting surgeons for specific procedures.

"In years past, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Cost of copper must rise double to meet basic copper needs

A gel for wounds that won’t heal

Iron, carbon, and the art of toxic cleanup

Organic soil amendments work together to help sandy soils hold water longer, study finds

Hidden carbon in mangrove soils may play a larger role in climate regulation than previously thought

Weight-loss wonder pills prompt scrutiny of key ingredient

Nonprofit leader Diane Dodge to receive 2026 Penn Nursing Renfield Foundation Award for Global Women’s Health

Maternal smoking during pregnancy may be linked to higher blood pressure in children, NIH study finds

New Lund model aims to shorten the path to life-saving cell and gene therapies

Researchers create ultra-stretchable, liquid-repellent materials via laser ablation

Combining AI with OCT shows potential for detecting lipid-rich plaques in coronary arteries

SeaCast revolutionizes Mediterranean Sea forecasting with AI-powered speed and accuracy

JMIR Publications’ JMIR Bioinformatics and Biotechnology invites submissions on Bridging Data, AI, and Innovation to Transform Health

Honey bees navigate more precisely than previously thought

Air pollution may directly contribute to Alzheimer’s disease

Study finds early imaging after pediatric UTIs may do more harm than good

UC San Diego Health joins national research for maternal-fetal care

New biomarker predicts chemotherapy response in triple-negative breast cancer

Treatment algorithms featured in Brain Trauma Foundation’s update of guidelines for care of patients with penetrating traumatic brain injury

Over 40% of musicians experience tinnitus; hearing loss and hyperacusis also significantly elevated

Artificial intelligence predicts colorectal cancer risk in ulcerative colitis patients

Mayo Clinic installs first magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia system for cancer research in the US

Calibr-Skaggs and Kainomyx launch collaboration to pioneer novel malaria treatments

JAX-NYSCF Collaborative and GSK announce collaboration to advance translational models for neurodegenerative disease research

Classifying pediatric brain tumors by liquid biopsy using artificial intelligence

Insilico Medicine initiates AI driven collaboration with leading global cancer center to identify novel targets for gastroesophageal cancers

Immunotherapy plus chemotherapy before surgery shows promise for pancreatic cancer

A “smart fluid” you can reconfigure with temperature

New research suggests myopia is driven by how we use our eyes indoors

Scientists develop first-of-its-kind antibody to block Epstein Barr virus

[Press-News.org] Different genes behind same adaptation to thin airApparent example of convergent human evolution on 2 continents