(Press-News.org) New research by a University of Alberta archeologist may lead to a rethinking of how, when and from where our ancestors left Africa.

U of A researcher and anthropology chair Pamela Willoughby's explorations in the Iringa region of southern Tanzania yielded fossils and other evidence that records the beginnings of our own species, Homo sapiens. Her research, recently published in the journal Quaternary International, may be key to answering questions about early human occupation and the migration out of Africa about 60,000 to 50,000 years ago, which led to modern humans colonizing the globe.

From two sites, Mlambalasi and nearby Magubike, she and members of her team, the Iringa Region Archaeological Project, uncovered artifacts that outline continuous human occupation between modern times and at least 200,000 years ago, including during a late Ice Age period when a near extinction-level event, or "genetic bottleneck," likely occurred.

Now, Willoughby and her team are working with people in the region to develop this area for ecotourism, to assist the region economically and create incentives to protect its archeological history.

"Some of these sites have signs that people were using them starting around 300,000 years ago. In fact, they're still being used today," she said. "But the idea that you have such ancient human occupation preserved in some of these places is pretty remarkable."

Magubike: Home to a modern Stone Age family?

Willoughby says one of the fascinating things about Magubike is the presence of a large rock shelter with an intact overhanging roof. The excavations yielded unprecedented ancient artifacts and fossils from under this roof. Samples from the site date from the earliest stages of the middle Stone Age to the Iron Age. The earlier deposits include human teeth and artifacts such as animal bones, shells and thousands of flaked stone tools.

The Iron Age finds can be dated using radiocarbon, but the older deposits must go through more specialized processes, such as electron spin resonance, to determine their age. Other parts of the Magubike rock shelter, excavated in 2006 and 2008, include occupations from after the middle Stone Age. Taken together, this information could be crucial to tracking the evolutionary development of the inhabitants.

"What's important about the whole sequence is that we may have a continuous record of human occupation," said Willoughby. "If we do—and we can prove it through these special dating techniques—then we have a place people lived in over the bottleneck."

Rugged, hilly terrain may have been key to survival

The team made similar findings at Mlambalasi, about 20 kilometres from Magubike. Among the findings at this site was a fragmentary human skeleton that probably dates to the late Pleistocene Ice Age—after the out-of-Africa expansion but at the end of the bottleneck period. The bottleneck theory explains what geneticists have found by studying the mitochondrial DNA of living people—that all non-Africans are descended from one lineage of people who left Africa about 50,000 years ago.

Reconstructions of past environments through pollen and other archeological records in Iringa suggest that people abandoned the lowland, tropical and coastal areas during that period but remained in the highlands, where vegetation has remained mostly unchanged over the last 50,000 years. Those who moved to higher ground may have found what is likely one of the few places that facilitated their survival and forced their adaptation. Further testing will determine whether these findings point to a clearer link to our African ancestors—a find Willoughby says could put that region of Tanzania on many archeologists' radar.

"It was only about 20 years ago that people recognized that modern Homo sapiens actually had an African ancestry, and everyone was focused on looking at early Homo sapiens in Europe who appeared around 40,000 years ago," she said. "But we now know that as far as back as around 200,000 years ago, Africa was inhabited by people who were already physically exactly like us today or really close to being the same as us. All of a sudden, it's not Europe in this time period that's really important, it's Africa."

Engaging community yields co-operation, opportunity

Along with its scientific significance, Willoughby's work may be a linchpin to potential economic growth for the region. Since 2005, when a local cultural officer showed her the sites, she has been sharing information about her research with local citizens, schools and government—opening up opportunities for more research and co-operation. She keeps the region informed of the team's findings through posters distributed around Iringa, and has asked for and accepted assistance from local scholars. Now the community is also looking for her help in establishing the historic sites as a tourist attraction that will benefit the region.

Willoughby says she feels fortunate to have the support of the Tanzanian people. She tells people it is a shared history she is uncovering, something she is honoured to be able to do.

"They're telling me, 'You're putting Iringa on the map,'" she said. "As long as they keep letting me work there, and keep letting the people working with me work there, we'll be happy."

INFORMATION:

Tracing humanity's African ancestry may mean rewriting 'out of Africa' dates

UAlberta archeologist's new research may lead to rethinking how and when our ancestors left Africa to colonize the globe

2012-12-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Better tools for saving water and keeping peaches healthy

2012-12-14

Peach growers in California may soon have better tools for saving water because of work by U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) scientists in Parlier, Calif.

Agricultural Research Service (ARS) scientist Dong Wang is evaluating whether infrared sensors and thermal technology can help peach growers decide precisely when to irrigate in California's San Joaquin Valley. ARS is USDA's principal intramural scientific research agency, and the research supports the USDA priority of promoting international food security.

Irrigation is the primary source of water for agriculture ...

Dark Ages scourge enlightens modern struggle between man and microbes

2012-12-14

The plague-causing bacteria Yersinia pestis evades detection and establishes a stronghold without setting off the body's early alarms.

New discoveries reported this week help explain how the stealthy agent of Black Death avoids tripping a self-destruct mechanism inside germ-destroying cells.

The authors of the study, appearing in the Dec. 13 issue of Cell Host & Microbe, are Dr. Christopher N. LaRock of the University of Washington Department of Microbiology and Dr. Brad Cookson, UW professor of microbiology and laboratory medicine.

Normally, certain defender cells ...

3 new species of venomous primate identified by MU researcher

2012-12-14

A venomous primate with two tongues would seem safe from the pet trade, but the big-eyed, teddy-bear face of the slow loris (Nycticebus sp.) has made them a target for illegal pet poachers throughout the animal's range in southeastern Asia and nearby islands. A University of Missouri doctoral student and her colleagues recently identified three new species of slow loris. The primates had originally been grouped with another species. Dividing the species into four distinct classes means the risk of extinction is greater than previously believed for the animals but could ...

Engineers roll up their sleeves -- and then do same with inductors

2012-12-14

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — On the road to smaller, high-performance electronics, University of Illinois researchers have smoothed one speed bump by shrinking a key, yet notoriously large element of integrated circuits.

Three-dimensional rolled-up inductors have a footprint more than 100 times smaller without sacrificing performance. The researchers published their new design paradigm in the journal Nano Letters.

"It's a new concept for old technology," said team leader Xiuling Li, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Illinois.

Inductors, ...

Study reveals a remarkable symmetry in black hole jets

2012-12-14

Black holes range from modest objects formed when individual stars end their lives to behemoths billions of times more massive that rule the centers of galaxies. A new study using data from NASA's Swift satellite and Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope shows that high-speed jets launched from active black holes possess fundamental similarities regardless of mass, age or environment. The result provides a tantalizing hint that common physical processes are at work.

"What we're seeing is that once any black hole produces a jet, the same fixed fraction of energy generates the ...

NASA sees intensifying tropical cyclone moving over Samoan Islands

2012-12-14

VIDEO:

NASA's TRMM satellite passed above an intensifying Tropical Cyclone Evan on Dec. 11 at 1759 UTC (12:59 p.m. EST/U.S.) and saw the tallest thunderstorms around Evan's center of circulation reached...

Click here for more information.

NASA satellites have been monitoring Tropical Cyclone Evan and providing data to forecasters who expected the storm to intensify. On Dec. 13, Evan had grown from a tropical storm into a cyclone as NASA satellites observed cloud formation, ...

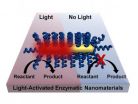

Rice uses light to remotely trigger biochemical reactions

2012-12-14

HOUSTON – (Dec. 13, 2012) – Since Edison's first bulb, heat has been a mostly undesirable byproduct of light. Now researchers at Rice University are turning light into heat at the point of need, on the nanoscale, to trigger biochemical reactions remotely on demand.

The method created by the Rice labs of Michael Wong, Ramon Gonzalez and Naomi Halas and reported today in the American Chemical Society journal ACS Nano makes use of materials derived from unique microbes – thermophiles – that thrive at high temperatures but shut down at room temperature.

The Rice project ...

Team solves mystery associated with DNA repair

2012-12-14

CHAMPAIGN, lll. — Every time a human or bacterial cell divides it first must copy its DNA. Specialized proteins unzip the intertwined DNA strands while others follow and build new strands, using the originals as templates. Whenever these proteins encounter a break – and there are many – they stop and retreat, allowing a new cast of molecular players to enter the scene.

Scientists have long sought to understand how one of these players, a repair protein known as RecA in bacterial cells, helps broken DNA find a way to bridge the gap. They knew that RecA guided a broken ...

More signs of the benefits of marriage?

2012-12-14

TORONTO, Dec. 13, 2012—There's new evidence about the benefits of marriage.

Women who are married suffer less partner abuse, substance abuse or post-partum depression around the time of pregnancy than women who are cohabitating or do not have a partner, a new study has found.

Unmarried women who lived with their partners for less than two years were more likely to experience at least one of the three problems. However, these problems became less frequent the longer the couple lived together.

The problems were most common among women who were separated or divorced, especially ...

Top officials meet at ONR as Arctic changes quicken

2012-12-14

ARLINGTON, Va.—The Navy's chief of naval research, Rear Adm. Matthew Klunder, met this week with leaders from U.S. and Canadian government agencies to address research efforts in the Arctic, in response to dramatic and accelerating changes in summer sea ice coverage.

"Our Sailors and Marines need to have a full understanding of the dynamic Arctic environment, which will be critical to protecting and maintaining our national, economic and security interests," said Klunder. "Our research will allow us to know what's happening, to predict what is likely to come for the region, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Effectiveness of exercise to ease osteoarthritis symptoms likely minimal and transient

Cost of copper must rise double to meet basic copper needs

A gel for wounds that won’t heal

Iron, carbon, and the art of toxic cleanup

Organic soil amendments work together to help sandy soils hold water longer, study finds

Hidden carbon in mangrove soils may play a larger role in climate regulation than previously thought

Weight-loss wonder pills prompt scrutiny of key ingredient

Nonprofit leader Diane Dodge to receive 2026 Penn Nursing Renfield Foundation Award for Global Women’s Health

Maternal smoking during pregnancy may be linked to higher blood pressure in children, NIH study finds

New Lund model aims to shorten the path to life-saving cell and gene therapies

Researchers create ultra-stretchable, liquid-repellent materials via laser ablation

Combining AI with OCT shows potential for detecting lipid-rich plaques in coronary arteries

SeaCast revolutionizes Mediterranean Sea forecasting with AI-powered speed and accuracy

JMIR Publications’ JMIR Bioinformatics and Biotechnology invites submissions on Bridging Data, AI, and Innovation to Transform Health

Honey bees navigate more precisely than previously thought

Air pollution may directly contribute to Alzheimer’s disease

Study finds early imaging after pediatric UTIs may do more harm than good

UC San Diego Health joins national research for maternal-fetal care

New biomarker predicts chemotherapy response in triple-negative breast cancer

Treatment algorithms featured in Brain Trauma Foundation’s update of guidelines for care of patients with penetrating traumatic brain injury

Over 40% of musicians experience tinnitus; hearing loss and hyperacusis also significantly elevated

Artificial intelligence predicts colorectal cancer risk in ulcerative colitis patients

Mayo Clinic installs first magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia system for cancer research in the US

Calibr-Skaggs and Kainomyx launch collaboration to pioneer novel malaria treatments

JAX-NYSCF Collaborative and GSK announce collaboration to advance translational models for neurodegenerative disease research

Classifying pediatric brain tumors by liquid biopsy using artificial intelligence

Insilico Medicine initiates AI driven collaboration with leading global cancer center to identify novel targets for gastroesophageal cancers

Immunotherapy plus chemotherapy before surgery shows promise for pancreatic cancer

A “smart fluid” you can reconfigure with temperature

New research suggests myopia is driven by how we use our eyes indoors

[Press-News.org] Tracing humanity's African ancestry may mean rewriting 'out of Africa' datesUAlberta archeologist's new research may lead to rethinking how and when our ancestors left Africa to colonize the globe