(Press-News.org) Daejeon, Republic of Korea, December 18th, 2012—Cell phones are becoming ever smarter, savvy enough to tell police officers where to go to find a missing person or recommend a rescue team where they should search for survivors when fire erupts in tall buildings. Although still in its nascent stages, indoor positioning system will soon be an available feature on mobile phones.

People widely rely on the Global Positioning System (GPS) for location information, but GPS does not work well in indoor spaces or urban canyons with streets cutting through dense blocks of high-rise buildings and structures. GPS requires a clear view to communicate with satellites because its signals become attenuated or scattered by roofs, walls, and other objects. In addition, GPS is only one-third as accurate in the vertical direction as it is in the horizontal, making it impossible to locate a person or object within the floors of skyscrapers.

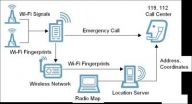

For indoor positioning, location-based service providers including mobile device makers have mostly used a combination of GPS and wireless network systems such as WiFi, cellular connectivity, Ultra Wide Band (UWB), or Radio-frequency Identification (RFID). For example, the WiFi Positioning System (WPS) collects both GPS and WiFi signals, and many companies including Google and Apple utilize this technology to provide clients with location information services.

Professor Dong-Soo Han from the Department of Computer Science, KAIST, explained, "WPS is helpful to a certain extent, but it is not sufficient because the technology needs GPS signals to tag the location of WiFi fingerprints collected from mobile devices. Therefore, even if you are surrounded by rich WiFi signals, they can be useless unless accompanied with GPS signals. Our research team tried to solve this problem and finally came up with a radio map that is created based on WiFi fingerprints only."

Professor Han and his research team have recently developed a new method to build a WiFi radio map that does not require GPS signals. WiFi fingerprints are a set of WiFi signals captured by a mobile device and the measurements of received WiFi signal strengths (RSSs) from access points surrounding the device. A WiFi radio map shows the RSSs of WiFi access points (APs) at different locations in a given environment. Therefore, each WiFi fingerprint on the radio map is connected to location information.

The KAIST research team collected fingerprints from users' smartphones every 30 minutes through the modules embedded in mobile platforms, utilities, or applications and analyzed the characteristics of the collected fingerprints. As a result, Professor Dong-Soo Han said,

"We discovered that mobile devices such as cell phones are not necessarily on the move all the time, meaning that they have locations where they stay for a certain period of time on a regular basis. If you have a full-time job, then your phone, at least, has a fixed location of home and office."

By using smartphone users' home and office addresses as location references Professor Han classified fingerprints collected from the phones into two groups: home and office. He then converted each home and office address into geographic coordinates (with the help of Google's geocoding) to obtain the location of the collected fingerprints. The WiFi radio map has both the fingerprints and coordinates whereby the location of the phones can be identified or tracked.

For evaluation, the research team selected four areas in Korea (a mix of commercial and residential locations), collected 7,000 WiFi fingerprints at 400 access points in each area, and created a WiFi radio map. The tests, conducted in each area, showed that location accuracy becomes hinged on the volume of data collected, and once the data collection rate rises above 50%, the average error distance is within less than 10m.

Professor Han added, "Although there seem to be many issues like privacy protection that have to be cleared up before commercializing this technology, there is no doubt that we will face a greater demand for indoor positioning system in the near future. People will eventually have just as much desire to know their locations in indoor environments as in outdoor environments."

Once the address-based radio map is fully developed for commercial use, home- and office-level location identification will be possible, thereby opening the door for further applications such as emergency rescue or indoor location-based services that pinpoint the location of lost cell phones, missing persons, and kidnapped children, or that find stores and restaurants offering promotional sales.

INFORMATION:

For additional information:

Professor Dong-Soo Han (+82-42-350-3562 or dshan@kaist.ac.kr)

Indoor Positioning Research Center at KAIST (http://isilab.kaist.ac.kr)

KAIST announces a major breakthrough in high-precision indoor positioning

Finding victims of earthquakes buried under the piles of rubble will be easier and more accurate when an address-based radio map is available

2012-12-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Silent stroke can cause Parkinson's disease

2012-12-18

Scientists at The University of Manchester have for the first time identified why a patient who appears outwardly healthy may develop Parkinson's disease.

Whilst conditions such as a severe stroke have been linked to the disease, for many sufferers the tremors and other symptoms of Parkinson's disease can appear to come out of the blue. Researchers at the university's Faculty of Life Sciences have now discovered that a small stroke, also known as a silent stroke, can cause Parkinson's disease. Their findings have been published in the journal "Brain Behaviour and Immunity".

Unlike ...

Prehistoric ghosts revealing new details

2012-12-18

Scientists at The University of Manchester have used synchrotron-based imaging techniques to identify previously unseen anatomy preserved in fossils.

Their work on a 50 million year old lizard skin identified the presence of teeth (invisible to visible light), demonstrating for the first time that this fossil animal was more than just a skin moult. This was only possible using some of the brightest light in the universe, x-rays generated by a synchrotron.

Dr Phil Manning, Dr Nick Edwards, Dr Roy Wogelius and colleagues from the Palaeontology Research group used Synchrotron ...

Research finds crisis in Syria has Mesopotamian precedent

2012-12-18

Research carried out at the University of Sheffield has revealed intriguing parallels between modern day and Bronze-Age Syria as the Mesopotamian region underwent urban decline, government collapse, and drought.

Dr Ellery Frahm from the University of Sheffield's Department of Archaeology made the discoveries by studying stone tools of obsidian, razor-sharp volcanic glass, crafted in the region about 4,200 years ago.

Dr Frahm used artefacts unearthed from the archaeological site of Tell Mozan, known as Urkesh in antiquity, to trace what happened to trade and social networks ...

pH measurements: How to see the real face of electrochemistry and corrosion?

2012-12-18

For several decades antimony electrodes have been used to measure the acidity/basicity – and so to determine the pH value. Unfortunately, they allow for measuring pH changes of solutions only at a certain distance from electrodes or corroding metals. Researchers at the Institute of Physical Chemistry of the Polish Academy of Sciences developed a method for producing antimony microelectrodes that allow for measuring pH changes just over the metal surface, at which chemical reactions take place.

Changes in solution acidity/basicity provide important information on the nature ...

Patients with diabetes may not receive best treatment to lower heart disease risk

2012-12-18

ANN ARBOR, Mich. — For some people with diabetes, there may be such a thing as too much care.

Traditional treatment to reduce risks of heart disease among patients with diabetes has focused on lowering all patients' blood cholesterol to a specific, standard level. But this practice may prompt the over-use of high-dose medications for patients who don't need them, according to new research from the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System (VAAAHS) and the University of Michigan Health System.

The study encourages a more individualized approach to treatment that adjusts treatment ...

Way to make one-way flu vaccine discovered by Georgia State researcher

2012-12-18

A new process to make a one-time, universal influenza vaccine has been discovered by a researcher at Georgia State University's Center for Inflammation, Immunity and Infection and his partners.

Associate Professor Sang-Moo Kang and his collaborators have found a way to make the one-time vaccine by using recombinant genetic engineering technology that does not use a seasonal virus.

Instead, the new vaccine uses a virus' small fragment that does not vary among the different strains of flu viruses.

By using the fragment and generating particles mimicking a virus in ...

Southampton researchers find a glitch' in pulsar 'glitch' theory

2012-12-18

Researchers from the University of Southampton have called in to question a 40 year-old theory explaining the periodic speeding up or 'glitching' of pulsars.

A pulsar is a highly magnetised rotating neutron star formed from the remains of a supernova. It emits a rotating beam of electromagnetic radiation, which can be detected by powerful telescopes when it sweeps past the Earth, rather like observing the beam of a lighthouse from a ship at sea.

Pulsars rotate at extremely stable speeds, but occasionally they speed up in brief events described as 'glitches' or 'spin-ups'. ...

Women earn more if they work in different occupations than men

2012-12-18

Women earn less money than men the more the sexes share the same occupations, a large-scale survey of 20 industrialised countries has found.

Researchers from the universities of Cambridge, UK, and Lakehead, Canada, found that the more women and men keep to different trades and professions, the more equal is the overall pay average for the two sexes in a country.

The researchers attribute the surprising results to the fact that when there are few men in an occupation, women have more chance to get to the top and earn more. But where there are more equal numbers of ...

Visions of snowflakes: An American Chemical Society holiday video

2012-12-18

WASHINGTON, Dec. 18, 2012 — For everyone with holiday visions of snowflakes dancing in their heads, the American Chemical Society, the world's largest scientific society, today issued a video explaining how dust, water, cold and air currents collaborate to form these symbols of the season. It's all there in an episode of Bytesize Science, the award-winning video series produced by the ACS Office of Public Affairs at www.BytesizeScience.com.

The video tracks formation of snowflakes from their origins in bits of dust in clouds that become droplets of water falling to Earth. ...

Mistaking OCD for ADHD has serious consequences

2012-12-18

On the surface, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) appear very similar, with impaired attention, memory, or behavioral control. But Prof. Reuven Dar of Tel Aviv University's School of Psychological Sciences argues that these two neuropsychological disorders have very different roots — and there are enormous consequences if they are mistaken for each other.

Prof. Dar and fellow researcher Dr. Amitai Abramovitch, who completed his PhD under Prof. Dar's supervision, have determined that despite appearances, OCD and ACHD ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

High risk of readmission and death among heart failure patients

Code for Earth launches 2026 climate and weather data challenges

Three women named Britain’s Brightest Young Scientists, each winning ‘unrestricted’ £100,000 Blavatnik Awards prize

Have abortion-related laws affected broader access to maternal health care?

Do muscles remember being weak?

Do certain circulating small non-coding RNAs affect longevity?

How well are international guidelines followed for certain medications for high-risk pregnancies?

New blood test signals who is most likely to live longer, study finds

Global gaps in use of two life-saving antenatal treatments for premature babies, reveals worldwide analysis

Bug beats: caterpillars use complex rhythms to communicate with ants

High-risk patients account for 80% of post-surgery deaths

Celebrity dolphin of Venice doesn’t need special protection – except from humans

Tulane study reveals key differences in long-term brain effects of COVID-19 and flu

The long standing commercialization challenge of lithium batteries, often called the dream battery, has been solved.

New method to remove toxic PFAS chemicals from water

The nanozymes hypothesis of the origin of life (on Earth) proposed

Microalgae-derived biochar enables fast, low-cost detection of hydrogen peroxide

Researchers highlight promise of biochar composites for sustainable 3D printing

Machine learning helps design low-cost biochar to fight phosphorus pollution in lakes

Urine tests confirm alcohol consumption in wild African chimpanzees

Barshop Institute to receive up to $38 million from ARPA-H, anchoring UT San Antonio as a national leader in aging and healthy longevity science

Anion-cation synergistic additives solve the "performance triangle" problem in zinc-iodine batteries

Ancient diets reveal surprising survival strategies in prehistoric Poland

Pre-pregnancy parental overweight/obesity linked to next generation’s heightened fatty liver disease risk

Obstructive sleep apnoea may cost UK + US economies billions in lost productivity

Guidelines set new playbook for pediatric clinical trial reporting

Adolescent cannabis use may follow the same pattern as alcohol use

Lifespan-extending treatments increase variation in age at time of death

From ancient myths to ‘Indo-manga’: Artists in the Global South are reframing the comic

Putting some ‘muscle’ into material design

[Press-News.org] KAIST announces a major breakthrough in high-precision indoor positioningFinding victims of earthquakes buried under the piles of rubble will be easier and more accurate when an address-based radio map is available