(Press-News.org) Working with fruit flies, Johns Hopkins scientists have decoded the activity of protein signals that let certain nerve cells know when and where to branch so that they reach and connect to their correct muscle targets. The proteins' mammalian counterparts are known to have signaling roles in immunity, nervous system and heart development, and tumor progression, suggesting broad implications for human disease research. A report of the research was published online Nov. 21 in the journal Neuron.

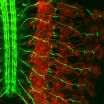

To control muscle movements, fruit flies, like other animals, have a set of nerve cells called motor neurons that connect muscle fibers to the nerve cord, a structure similar to the spinal cord, which in turn connects to the brain. During embryonic development, the nerve cells send wire-like projections, or axons, from the nerve cord structure out to their targets. Initially, multiple axons travel together in a convoy, but as they move forward, some axons must exit the "highway" at specific points to reach particular targets.

In their experiments, the researchers learned that axons travelling together have proteins on their surfaces that act like two-way radios, allowing the axons to communicate with each other and coordinate their travel patterns, thus ensuring that every muscle fiber gets connected to a nerve cell. "When axons fail to branch, or when they branch too early and too often, fruits flies, and presumably other animals, can be left without crucial muscle-nerve connections," says Alex Kolodkin, Ph.D., a Howard Hughes investigator and professor of neuroscience at the Institute for Basic Biomedical Sciences at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

At the center of the communications system, Kolodkin says, is a protein called Sema-1a, already known to reside on the surface of motor neuron axons. If a neighboring axon has a different protein, called PlexA, on its surface, it will be repulsed by Sema-1a and will turn away from the axon bundle. So Sema-1a acts as an instructional signal and PlexA as its receptor. In the fruit fly study, the scientists discovered that Sema-1a can also act as a receptor for PlexA. "We used to think that this pair of surface proteins acted as a one-way radio, with information flowing in a single direction," says Kolodkin. "What we found is that instructional information flows both ways."

The Johns Hopkins team identified the "two-way" system by knocking out and otherwise manipulating fruit fly genes and then watching what happened to motor neuron branching. In these experiments, the researchers uncovered still other proteins located within the motor axons that Sema-1a interacts with after receiving a PlexA signal. When the gene for a protein called Pebble was deleted, for example, motor axons bunched together and didn't branch. When the gene for RhoGAPp190 was deleted, motor axons branched too soon and failed to recognize their target muscles.

Through a series of biochemical tests, Kolodkin's team found that Pebble and RhoGAPp190 both act on a third protein, Rho1. When Rho1 is activated, it collapses the supporting structures within an axon, making it "limp" and unable to continue toward a target. Sema-1a can bind to Pebble or to RhoGAPp190, and subsequently, these proteins can bind to Rho1. Binding to Pebble activates Rho1, causing axons to branch away from each other. However, binding to RhoGAPp190 shuts down Rho1, causing axons to remain bunched together. Thus, says Kolodkin, balance in the amounts of available Pebble and RhoGAPp190 can determine axon behavior, although what determines this balance is still unknown.

"This signaling is complex and we still don't understand how it's all controlled, but we're one step closer now," says Kolodkin. He notes that "a relative" of the Sema-1a protein in humans has already been implicated in schizophrenia, although details of this protein's role in disease remain unclear. "Our experiments affirm how important this protein is to study and understand," adds Kolodkin.

INFORMATION:

Other authors on the paper include Sangyun Jeong and Katarina Juhaszova of The Johns Hopkins University.

This work was supported by funds from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01 NS35165) and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

On the Web:

Link to article in Neuron: http://www.cell.com/neuron/abstract/S0896-6273%2812%2900853-7

Kolodkin Lab: http://neuroscience.jhu.edu/AlexKolodkin.php

Kolodkin HHMI Profile: http://www.hhmi.org/research/investigators/kolodkin_bio.html

Molecular '2-way radio' directs nerve cell branching and connectivity

Insect research yields insights for muscle control and nerve disorders in mammals, including humans

2013-01-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

UI researcher learns mechanism of hearing is similar to car battery

2013-01-08

University of Iowa biologist Daniel Eberl and his colleagues have shown that one of the mechanisms involved in hearing is similar to the battery in your car.

And if that isn't interesting enough, the UI scientists advanced their knowledge of human hearing by studying a similar auditory system in fruit flies—and by making use of the fruit fly "love song."

To see how the mechanism of hearing resembles a battery, you need to know that the auditory system of the fruit fly contains a protein that functions as a sodium/potassium pump, often called the sodium pump for short, ...

AMSSM issues position statement on sport-related concussions

2013-01-08

Philadelphia, Pa. (January 7, 2013) - Athletes with concussions must be held out of practice or play until all symptoms have resolved, to avoid the risk of further injury during the vulnerable period before the brain has recovered. That's among the key recommendations in the new American Medical Society for Sports Medicine (AMSSM) position statement on concussions in sport, which appears in the January issue of Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine. The journal is published by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, a part of Wolters Kluwer Health.

At a time of increased concern ...

Penn researchers show new level of control over liquid crystals

2013-01-08

PHILADELPHIA — Directed assembly is a growing field of research in nanotechnology in which scientists and engineers aim to manufacture structures on the smallest scales without having to individually manipulate each component. Rather, they set out precisely defined starting conditions and let the physics and chemistry that govern those components do the rest.

An interdisciplinary team of researchers from the University of Pennsylvania has shown a new way to direct the assembly of liquid crystals, generating small features that spontaneously arrange in arrays based on ...

Computer scientists find vulnerabilities in Cisco VoIP phones

2013-01-08

New York, NY—January 7, 2013—Columbia Engineering's Computer Science PhD candidate Ang Cui and Computer Science Professor Salvatore Stolfo have found serious vulnerabilities in Cisco VoIP (voice over internet protocol) telephones, devices used around the world by a broad range of networked organizations from governments to banks to major corporations, and beyond. In particular, they have discovered troubling security breaches with Cisco's VoIP phone technology. At a recent conference on the security of connected devices, Cui demonstrated how they can easily insert malicious ...

Black and Hispanic patients less likely to complete substance abuse treatment, Penn study shows

2013-01-08

PHILADELPHIA – Roughly half of all black and Hispanic patients who enter publicly funded alcohol treatment programs do not complete treatment, compared to 62 percent of white patients, according to a new study from a team of researchers including the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Comparable disparities were also identified for drug treatment program completion rates. The study, published in the latest issue of Health Affairs, shows that completion disparities among racial groups are likely related to differences in socioeconomic status and, ...

Obese moms risk having babies with low vitamin D

2013-01-08

CHICAGO --- Women who are obese at the start of their pregnancy may be passing on insufficient levels of vitamin D to their babies, according to a new Northwestern Medicine® study.

The study found that babies born to lean mothers had a third higher amount of vitamin D compared to babies born to obese moms.

Vitamin D is fat-soluble, and previous studies have found that people who are obese tend to have lower levels of the vitamin in their blood. In this study, both obese and lean mothers had very similar levels of vitamin D at the end of their pregnancies, yet obese ...

Southern Medical Journal presents special issue on disaster preparedness

2013-01-08

Philadelphia, Pa. (January 7, 2013) – Surveys suggest that while most US physicians are willing to play a role in responding to natural and manmade disasters, most do not feel adequately prepared to fulfill that role. Toward helping physicians and health care systems understand and fulfill their obligation to provide medical care in disasters, the January Southern Medical Journal is a special issue on disaster medicine and physician preparedness. The official journal of the Southern Medical Association, the SMJ is published by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, a part of Wolters ...

Study looks at how states decide which child receives early intervention for developmental problems

2013-01-08

AURORA, Colo. (Jan. 7, 2013) A new study out by researchers at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, found large differences in the criteria that states use to determine eligibility for Part C early intervention services for infants and toddlers who have developmental delays. A developmental delay is any significant lag in a child's development as compared with typical child development.

Current eligibility criteria for Part C services vary from state to state. With their colleagues, Steven Rosenberg, PhD, associate professor, University of Colorado Department ...

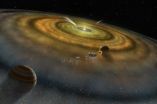

At least 1 in 6 stars has an Earth-sized planet

2013-01-08

The quest for a twin Earth is heating up. Using NASA's Kepler spacecraft, astronomers are beginning to find Earth-sized planets orbiting distant stars. A new analysis of Kepler data shows that about 17 percent of stars have an Earth-sized planet in an orbit closer than Mercury. Since the Milky Way has about 100 billion stars, there are at least 17 billion Earth-sized worlds out there.

Francois Fressin, of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA), presented the analysis today in a press conference at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Long Beach, ...

Exocomets may be as common as exoplanets

2013-01-08

Comets trailing wispy tails across the night sky are a beautiful byproduct of our solar system's formation, icy leftovers from 4.6 billion years ago when the planets coalesced from rocky rubble.

The discovery by astronomers at the University of California, Berkeley, and Clarion University in Pennsylvania of six likely comets around distant stars suggests that comets – dubbed "exocomets" – are just as common in other stellar systems with planets.

Though only one of the 10 stars now thought to harbor comets is known to harbor planets, the fact that all these stars have ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Barshop Institute to receive up to $38 million from ARPA-H, anchoring UT San Antonio as a national leader in aging and healthy longevity science

Anion-cation synergistic additives solve the "performance triangle" problem in zinc-iodine batteries

Ancient diets reveal surprising survival strategies in prehistoric Poland

Pre-pregnancy parental overweight/obesity linked to next generation’s heightened fatty liver disease risk

Obstructive sleep apnoea may cost UK + US economies billions in lost productivity

Guidelines set new playbook for pediatric clinical trial reporting

Adolescent cannabis use may follow the same pattern as alcohol use

Lifespan-extending treatments increase variation in age at time of death

From ancient myths to ‘Indo-manga’: Artists in the Global South are reframing the comic

Putting some ‘muscle’ into material design

House fires release harmful compounds into the air

Novel structural insights into Phytophthora effectors challenge long-held assumptions in plant pathology

Q&A: Researchers discuss potential solutions for the feedback loop affecting scientific publishing

A new ecological model highlights how fluctuating environments push microbes to work together

Chapman University researcher warns of structural risks at Grand Renaissance Dam putting property and lives in danger

Courtship is complicated, even in fruit flies

Columbia announces ARPA-H contract to advance science of healthy aging

New NYUAD study reveals hidden stress facing coral reef fish in the Arabian Gulf

36 months later: Distance learning in the wake of COVID-19

Blaming beavers for flood damage is bad policy and bad science, Concordia research shows

The new ‘forever’ contaminant? SFU study raises alarm on marine fiberglass pollution

Shorter early-life telomere length as a predictor of survival

Why do female caribou have antlers?

How studying yeast in the gut could lead to new, better drugs

Chemists thought phosphorus had shown all its cards. It surprised them with a new move

A feedback loop of rising submissions and overburdened peer reviewers threatens the peer review system of the scientific literature

Rediscovered music may never sound the same twice, according to new Surrey study

Ochsner Baton Rouge expands specialty physicians and providers at area clinics and O’Neal hospital

New strategies aim at HIV’s last strongholds

Ambitious climate policy ensures reduction of CO2 emissions

[Press-News.org] Molecular '2-way radio' directs nerve cell branching and connectivityInsect research yields insights for muscle control and nerve disorders in mammals, including humans