(Press-News.org) PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — If you want to understand a novel, it helps to start from the beginning rather than trying to pick up the plot from somewhere in the middle. The same goes for analyzing a strand of DNA. The best way to make sense of it is to look at it head to tail.

Luckily, according to a new study by physicists at Brown University, DNA molecules have a convenient tendency to cooperate.

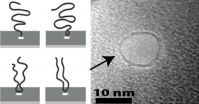

The research, published in the journal Physical Review Letters, looks at the dynamics of how DNA molecules are captured by solid-state nanopores, tiny holes that soon may help sequence DNA at lightning speed. The study found that when a DNA strand is captured and pulled through a nanopore, it's much more likely to start the journey at one of its ends, rather than being grabbed somewhere in the middle and pulled through in a folded configuration.

"We think this is an important advance for understanding how DNA molecules interact with these nanopores," said Derek Stein, assistant professor of physics at Brown, who performed the research with graduate students Mirna Mihovilivic and Nick Haggerty. "If you want to do sequencing or some other analysis, you want the molecule going through the pore head to tail."

Research into DNA sequencing with nanopores started a little over 15 years ago. The concept is fairly simple. A little hole, a few billionths of a meter across, is poked in a barrier separating two pools of salt water. An electric current is applied across the hole, which occasionally attracts a DNA molecule floating in the water. When that happens, the molecule is whipped through the pore in a fraction of a second. Scientists can then use sensors on the pore or other means to identify nucleotide bases, the building blocks of the genetic code.

The technology is advancing quickly, and the first nanopore sequencing devices are expected to be on the market very soon. But there are still basic questions about how molecules behave at the moment they're captured and before.

"What the molecules were doing before they're captured was a mystery and a matter of speculation," Stein said. "And we'd like to know because if you're trying to engineer something to control that molecule — to get it to do what you want it to do — you need to know what it's up to."

To find out what those molecules are up to, the researchers carefully tracked over 1,000 instances of a molecule zipping through a nanopore. The electric current through the pore provides a signal of how the molecule went through. Molecules that go through middle first have to be folded over in order to pass. That folded configuration takes up more space in the pore and blocks more of the current. So by looking at differences in the current, Stein and his team could count how many molecules went through head first and how many started somewhere in the middle.

The study found that molecules are several times more likely to be captured at or very near an end than at any other single point along the molecule.

"What we found was that ends are special places," Stein said. "The middle is different from an end, and that has a consequence for the likelihood a molecule starts its journey from the end or the middle."

Always room for Jell-O

As it turns out, there's an old theory that that explains these new experimental results quite well. It's the theory of Jell-O.

Jell-O is a polymer network — a mass of squiggly polymer strands that attach to each other at random junctions. The squiggly strands are the reason Jell-O is a jiggly, semi-solid. The way in which the polymer strands connect to each other is not unlike the way a DNA strand connects to a nanopore in the instant it's captured. In water, DNA molecules are jumbled up in random squiggles much like the gelatin molecules in Jell-O.

"There's some powerful theory that describes how many ways the polymers in Jell-O can arrange and attach themselves," Stein said. "That turns out to be perfectly applicable to the problem of where these DNA molecules get captured by a nanopore."

When applied to DNA, the Jell-O theory predicts that if you were to count up all the possible configurations of a DNA strand at the moment of capture, you would find that there are more configurations in which it is captured by its end, compared to other points along the strand. It's a bit like the odds of getting a pair in poker compared to the odds of getting three of a kind. You're more likely to get a pair simply because there are more pairs in the deck than there are triples.

This measure of all the possible configurations — a measure of what physicists refer to as the molecule's entropy — is all that's needed to explain why DNA tends to go head first. Some scientists had speculated that perhaps strands would be less likely to go through by the middle because folding them in half would require extra energy. But that folding energy appears not to matter at all. As Stein puts it, "The number of ways that a molecule can find itself with its head sticking in the pore is simply larger than the number of ways it can find itself with the middle touching the pore."

These theories of polymer networks have actually been around for a while. They were first proposed by the late Nobel laureate Pierre-Gilles de Gennes in the 1960s, and Bertrand Duplantier made key advances in the 1980s. Mihovilivic, Stein's graduate student and the lead author of this study, says this is actually one of the first lab tests of those theories.

"They couldn't be tested until now, when we can actually do single molecule measurements," she said. "[De Gennes] postulated that one day it would be possible to test this. I think he would have been very excited to see it happen."

INFORMATION:

DNA prefers to dive head first into nanopores

2013-01-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Scientists mimic fireflies to make brighter LEDs

2013-01-08

The nighttime twinkling of fireflies has inspired scientists to modify a light-emitting diode (LED) so it is more than one and a half times as efficient as the original. Researchers from Belgium, France, and Canada studied the internal structure of firefly lanterns, the organs on the bioluminescent insects' abdomens that flash to attract mates. The scientists identified an unexpected pattern of jagged scales that enhanced the lanterns' glow, and applied that knowledge to LED design to create an LED overlayer that mimicked the natural structure. The overlayer, which increased ...

Unlike we thought for 100 years: Molds are able to reproduce sexually

2013-01-08

For over 100 years, it was assumed that the penicillin-producing mould fungus Penicillium chrysogenum only reproduced asexually through spores. An international research team led by Prof. Dr. Ulrich Kück and Julia Böhm from the Chair of General and Molecular Botany at the Ruhr-Universität has now shown for the first time that the fungus also has a sexual cycle, i.e. two "genders". Through sexual reproduction of P. chrysogenum, the researchers generated fungal strains with new biotechnologically relevant properties - such as high penicillin production without the contaminating ...

Parasitic worms may help treat diseases associated with obesity

2013-01-08

Athens, Ga. – On the list of undesirable medical conditions, a parasitic worm infection surely ranks fairly high. Although modern pharmaceuticals have made them less of a threat in some areas, these organisms are still a major cause of disease and disability throughout much of the developing world.

But parasites are not all bad, according to new research by a team of scientists now at the University of Georgia, the Harvard School of Public Health, the Université François Rabelais in Tours, France, and the Central South University, Changsha, Hunan, China.

A study ...

PNAS: Shareholder responsibility could spur shift to sustainable energy

2013-01-08

The research carried out at IIASA in collaboration with the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research demonstrates that there is fundamental rigidity, known as lock-in, within the energy economy that favors the use of fossil fuels and nuclear power despite their large environmental and social costs. The researchers identify that this rigidity of the existing energy economy could be considerably reduced by introducing new rules that hold shareholders of companies liable for the damages caused by the companies they own. Allocating the liability between the company and ...

Females tagged in wasp mating game

2013-01-08

The flick of an antenna may be how a male wasp lays claim to his harem, according to new research at Simon Fraser University.

A team of biologists, led by former PhD graduate student Kelly Ablard, found that when a male targeted a female, he would approach from her from the left side, and once in range, uses the tip of his antenna to tap her antenna.

Ablard suggests the act transfers a yet unidentified specimen-specific pheromone onto the female's antenna that marks the female as "out of bounds," or "tagged."

The tagging-pheromone helps a male relocate the females ...

Rice University discovers that graphene oxide soaks up radioactive waste

2013-01-08

Graphene oxide has a remarkable ability to quickly remove radioactive material from contaminated water, researchers at Rice University and Lomonosov Moscow State University have found.

A collaborative effort by the Rice lab of chemist James Tour and the Moscow lab of chemist Stepan Kalmykov determined that microscopic, atom-thick flakes of graphene oxide bind quickly to natural and human-made radionuclides and condense them into solids. The flakes are soluble in liquids and easily produced in bulk.

The experimental results were reported in the Royal Society of Chemistry ...

Genetic matchmaking saves endangered frogs

2013-01-08

What if Noah got it wrong? What if he paired a male and a female animal thinking they were the same species, and then discovered they were not the same and could not produce offspring? As researchers from the Smithsonian's Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project race to save frogs from a devastating disease by breeding them in captivity, a genetic test averts mating mix-ups.

At the El Valle Amphibian Conservation Center, project scientists breed 11 different species of highland frogs threatened by the chytrid fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, which has already ...

New American Chemical Society video series: Conversations with Celebrated Scientists

2013-01-08

The American Chemical Society (ACS), the world's largest scientific society, today launched a new video series that will feature noted scientists discussing the status of knowledge in their fields, their own research, and its impacts and potential impacts on society. Chemistry over Coffee: Conversations with Celebrated Scientists is available at www.acs.org/ChemistryOverCoffee.

The launch episode features Chad Mirkin, Ph.D., and Paul Weiss, Ph.D., internationally known leaders in nanotechnology. Mirkin, director of Northwestern University's International Institute for ...

Teens susceptible to hepatitis B infection despite vaccination as infants

2013-01-08

New research reveals that a significant number of adolescents lose their protection from hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, despite having received a complete vaccination series as infants. Results in the January 2013 issue of Hepatology, a journal published by Wiley on behalf of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, suggest teens with high-risk mothers (those positive for HBeAg) and teens whose immune system fails to remember a previous viral exposure (immunological memory) are behind HBV reinfection.

Infection with HBV is a major global health concern ...

First study of Oregon's Hmong reveals surprising influences on cancer screenings

2013-01-08

CORVALLIS, Ore. – Cervical cancer rates for Hmong women are among the highest in the nation, yet past research has shown that cervical and breast cancer screening rates for this population are low – in part because of the Hmong's strong patriarchal culture.

However, a new study by Oregon State University researchers examining attitudes regarding breast and cervical cancer screening among Oregon's Hmong population shows a much more complicated picture. The study found that Hmong women often make their own health decisions, but in an environment in which screening is not ...