(Press-News.org) WASHINGTON — Scientists have long wondered how nerve cell activity in the brain's hippocampus, the epicenter for learning and memory, is controlled — too much synaptic communication between neurons can trigger a seizure, and too little impairs information processing, promoting neurodegeneration. Researchers at Georgetown University Medical Center say they now have an answer. In the January 10 issue of Neuron, they report that synapses that link two different groups of nerve cells in the hippocampus serve as a kind of "volume control," keeping neuronal activity throughout that region at a steady, optimal level.

"Think of these special synapses like the fingers of God and man touching in Michelangelo's famous fresco in the Sistine Chapel," says the study's senior investigator, Daniel Pak, PhD, an associate professor of pharmacology. "Now substitute the figures for two different groups of neurons that need to perform smoothly. The touching of the fingers, or synapses, controls activity levels of neurons within the hippocampus."

The hippocampus is a processing unit that receives input from the cortex and consolidates that information in terms of learning and memory. Neurons known as granule cells, located in the hippocampus' dentate gyrus, receive transmissions from the cortex. Those granule cells then pass that information to the other set of neurons (those in the CA3 region of the hippocampus, in this study) via the synaptic fingers.

Those fingers dial up, or dial down, the volume of neurotransmission from the granule cells to the CA3 region to keep neurotransmission in the learning and memory areas of the hippocampus at an optimal flow — a concept known as homeostatic plasticity. "If granule cells try to transmit too much activity, we found, the synaptic junction tamps down the volume of transmission by weakening their connections, allowing the proper amount of information to travel to CA3 neurons," says Pak. "If there is not enough activity being transmitted by the granule cells, the synapses become stronger, pumping up the volume to CA3 so that information flow remains constant."

There are many such touching fingers in the hippocampus, connecting the so-called "mossy fibers" of the granule cells to neurons in the CA3 region. But importantly, not every one of the billions of neurons in the hippocampus needs to set its own level of transmission from one nerve cell to the other, says Pak.

To explain, he uses another analogy. "It had previously been thought that neurons act separately like cars, each working to keep their speed at a constant level even though signal traffic may be fast or slow. But we wondered how these neurons could process learning and memory information efficiently, while also regulating the speed by which they process and communicate that information.

"We believe, based on our study, that only the mossy fiber synapses on the CA3 neurons control the level of activity for the hippocampus — they are like the engine on a train that sets the speed for all the other cars, or neurons, attached to it," Pak says. "That frees up the other neurons to do the job they are tasked with doing — processing and encoding information in the forms of learning and memory."

Not only does the study offer a new model for how homeostatic plasticity in the hippocampus can co-exist with learning and memory, it also suggests a new therapeutic avenue to help patients with uncontrollable seizures, he says.

"The CA3 region is highly susceptible to seizures, so if we understand how homeostasis is maintained in these neurons, we could potentially manipulate the system. When there is an excessive level of CA3 neuronal activity in a patient, we could learn how to therapeutically turn it down."

###

The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health NS041218, NS080462, NS048085 and NS075278.

The authors report having no personal financial interests related to the study.

About Georgetown University Medical Center

Georgetown University Medical Center is an internationally recognized academic medical center with a three-part mission of research, teaching and patient care (through MedStar Health). GUMC's mission is carried out with a strong emphasis on public service and a dedication to the Catholic, Jesuit principle of cura personalis -- or "care of the whole person." The Medical Center includes the School of Medicine and the School of Nursing & Health Studies, both nationally ranked; Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, designated as a comprehensive cancer center by the National Cancer Institute; and the Biomedical Graduate Research Organization (BGRO), which accounts for the majority of externally funded research at GUMC including a Clinical Translation and Science Award from the National Institutes of Health.

END

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients frequently suffer from mineral bone disorder, which causes vascular calcification and, eventually, chronic heart failure. Similar to patients with CKD, mice with low levels of the protein klotho (klotho hypomorphic mice) also develop vascular calcification and have shorter life spans compared to normal mice. In this issue of the Journal of Clinical Investigation, Florian Lang and colleagues at the University of Tübingen in Germany, found that treatment with the mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist spironolactone reduced vascular calcification ...

Fusion genes are common chromosomal aberrations in many cancers, and can be used as prognostic markers and drug targets in clinical practice. In this issue of the Journal of Clinical Investigation, researchers led by Matti Annala at Tampere University of Technology in Finland identified a fusion between the FGFR3 and TACC3 genes in human glioblastoma samples. The protein produced by this fusion gene promoted tumor growth and progression in a mouse model of glioblastoma, while increased expression of either of the normal genes did not alter tumor progression. Ivan Babic ...

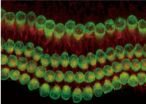

Extremely loud noise can cause irreversible hearing loss by damaging sound sensing cells in the inner ear that are not replaced. But researchers reporting in the January 9 issue of the Cell Press journal Neuron have successfully regenerated these cells in mice with noise-induced deafness, partially reversing their hearing loss. The investigators hope the technique may lead to development of treatments to help individuals who suffer from acute hearing loss.

While birds and fish are capable of regenerating sound sensing hair cells in the inner ear, mammals are not. Scientists ...

San Diego, California – January 9, 2013 – How does mathematics improve our understanding of weather and climate? Can mathematicians determine whether an extreme meteorological event is an anomaly or part of a general trend? Presentations touching on these questions will be given at the annual national mathematics conference in San Diego, California. New results will also be presented on the MJO (pronounced "mojo"), a tropical atmospheric wave which governs monsoons and also impacts rainfall in North America, and yet does not fit into any current computer models of the ...

NEW YORK (January 9, 2013) – Exposure to a chemical once used widely in plastic bottles and still found in aluminum cans appears to be associated with a biomarker for higher risk of heart and kidney disease in children and adolescents, according to an analysis of national survey data by NYU School of Medicine researchers published in the January 9, 2013, online issue of Kidney International, a Nature publication.

Laboratory studies suggest that even low levels of bisphenol A (BPA) like the ones identified in this national survey of children and adolescents increase oxidative ...

WASHINGTON—Video games have been blamed for contributing to the epidemic of childhood obesity in the United States. But a new study by researchers at the George Washington University School of Public Health and Health Services (SPHHS) suggests that certain blood-pumping video games can actually boost energy expenditures among inner city children, a group that is at high risk for unhealthy weight gain.

The study, "Can E-gaming be Useful for Achieving Recommended Levels of Moderate to Vigorous-Intensity Physical Activity in Inner-City Children," will appear January 9 in ...

PASADENA, Calif., January 9, 2013 – The presence of microscopic hematuria – blood found in urine that can't be seen by the naked eye – does not necessarily indicate the presence of cancer, according to a Kaiser Permanente Southern California study published in the journal Mayo Clinic Proceedings. The study suggests that tests routinely done on patients with this condition could be avoided and has led to the creation of a screening tool to better diagnose certain types of cancers.

The observational study examined the electronic health records of more than 4,000 patients ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- Two years of painstaking observation on the social interactions of a troop of free-ranging monkeys and an analysis of their family trees has found signs of natural selection affecting the behavior of the descendants.

Rhesus macaques who had large, strong networks tended to be descendants of similarly social macaques, according to a Duke University team of researchers. And their ability to recognize relationships and play nice with others also won them more reproductive success.

"If you are a more social monkey, then you're going to have greater reproductive ...

Boston (Jan. 9, 2013) — Hearing loss is a significant public health problem affecting close to 50 million people in the United States alone. Sensorineural hearing loss is the most common form and is caused by the loss of sensory hair cells in the cochlea. Hair cell loss results from a variety of factors including noise exposure, aging, toxins, infections, and certain antibiotics and anti-cancer drugs. Although hearing aids and cochlear implants can ameliorate the symptoms somewhat, there are no known treatments to restore hearing, because auditory hair cells in mammals, ...

Scientists at the University of Granada and Alcalá de Henares University have found out that not all isolated stem cells are equally valid in regenerative medicine and tissue engineering. In a paper recently published in the prestigious journal Tissue Engineering the researchers report that, contrary to what was thought, only a specific group of cord blood stem cells (CB-SC) maintained in culture are useful for therapeutic purposes.

At present, CB-SCs are key to regenerative medicine and tissue engineering. From all types of CB-SC those called "Wharton's jelly stem cells ...