(Press-News.org) HOUSTON – (Jan. 9, 2013) – Magma forms far deeper than geologists previously thought, according to new research at Rice University.

A group led by geologist Rajdeep Dasgupta put very small samples of peridotite under very large pressures in a Rice laboratory to determine that rock can and does liquify, at least in small amounts, as deep as 250 kilometers in the mantle beneath the ocean floor. He said this explains several puzzles that have bothered scientists.

Dasgupta is lead author of the paper to be published this week in Nature.

The mantle is the planet's middle layer, a buffer of rock between the crust – the top 5 miles or so – and the core. If one could compress millions of years of observation down to minutes, the mantle would look like a rolling mass of rising and falling material. This slow but constant convection brings materials from deep within the planet to the surface – and occasionally higher through volcanoes.

The Rice team focused on mantle beneath the ocean because that's where the crust is created and, Dasgupta said, "the connection between the interior and surface world is established." Silicate melts – aka magma – rise with the convective currents, cool and spread out to form the ocean crust. The starting point for melting has long been thought to be at 70 kilometers beneath the seafloor.

That has confounded geologists who suspected but could not demonstrate the existence of deeper silicate magma, said Dasgupta, an assistant professor of Earth science at Rice.

Scientists determine the mantle's density by measuring the speed of a seismic wave after an earthquake, from its origin to other points on the planet. These waves travel faster through solids than liquids, and geologists have been surprised to detect waves slowing down through what should be the mantle's express lane. "Seismologists have observed anomalies in their velocity data as deep as 200 kilometers beneath the ocean floor," Dasgupta said. "Based on our work, we show that trace amounts of magma are generated at this depth, which would potentially explain that."

The research also offers clues to the bulk electrical conductivity of the oceanic mantle, he said. "The magma at such depths has a high enough amount of dissolved carbon dioxide that its conductivity is very high," Dasgupta said. "As a consequence, we can explain the conductivity of the mantle, which we knew was very high but always struggled to explain."

Because humans have not yet dug deep enough to sample the mantle directly – though some are trying – researchers have to extrapolate data on rocks carried up to the surface. A previous study by Dasgupta determined that melting in the Earth's deep upper mantle is caused by the presence of carbon dioxide. The present study shows that carbon not only leads the charge to make carbonate fluid but also helps to make silicate magma at significant depths.

The researchers also found carbonated rock melts at significantly lower temperatures than non-carbonated rock. "This deep melting makes the silicate differentiation of the planet much more efficient than previously thought," Dasgupta said. "Not only that, this deep magma is the main agent to bring all the key ingredients for life – water and carbon – to the surface of the Earth."

In Dasgupta's high-pressure lab at Rice, volcanic rocks are windows to the planet's interior. The researchers crushed tiny rock samples that contain carbon dioxide to find out how deep magma forms.

"Our field of research is called experimental petrology," he said. "We have all the necessary tools to simulate very high pressures (up to nearly 750,000 pounds per square inch for these experiments) and temperatures. We can subject small amounts of rock samples to these conditions and see what happens."

They use powerful hydraulic presses to partially melt "rocks of interest" that contain tiny amounts of carbon to simulate what they believe is happening under equivalent pressures in the mantle. "When rocks come from deep in the mantle to shallower depths, they cross a certain boundary called the solidus, where rocks begin to undergo partial melting and produce magmas," Dasgupta said.

"Scientists knew the effect of a trace amount of carbon dioxide or water would be to lower this boundary, but our new estimation made it 150-180 kilometers deeper from the known depth of 70 kilometers," he said.

"What we are now saying is that with just a trace of carbon dioxide in the mantle, melting can begin as deep as around 200 kilometers. And when we incorporate the effect of trace water, the magma generation depth becomes at least 250 kilometers. This does not generate a large amount, but we show the extent of magma generation is larger than previously thought and, as a consequence, it has the capacity to affect geophysical and geochemical properties of the planet as a whole."

INFORMATION:

Co-authors of the paper are Rice graduate student Ananya Mallik and postdoctoral researcher Kyusei Tsuno; Research Professor Anthony Withers and Marc Hirschmann, the George and Orpha Gibson Chair of Earth and Planetary Sciences, at the University of Minnesota, and Greg Hirth, a professor of geological sciences at Brown University.

The study was supported by the National Science Foundation and a Packard Fellowship to Dasgupta.

Follow Rice News and Media Relations via Twitter @RiceUNews

Related Materials:

Melting in the Earth's deep upper mantle caused by carbon dioxide: http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v440/n7084/abs/nature04612.html

Dasgupta Group: http://earthscience.rice.edu/department/faculty/dasgupta/

Images for download:

http://news.rice.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Magma-1-web.jpg

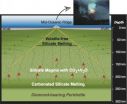

A schematic cross section of the Earth's interior below oceanic ridges shows the conditions of magma generation. Through experimentation on mantle rocks, Rice University researchers found evidence that magma forms as deep as 250 kilometers inside the Earth's, much deeper than previously thought. Such melting would help explain apparent geophysical and geochemical contradictions that have puzzled geologists for years. (Credit: Dasgupta Group/Rice University)

http://news.rice.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Magma-2-web.jpg

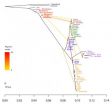

A microscopic sample of rock squeezed in a lab at Rice University to pressures it would experience hundreds of kilometers inside the Earth's mantle show evidence of magma (silicate melt) formation. New research led by Rice shows magma can form as deep as 250 kilometers inside the mantle. (Credit: Dasgupta Group/Rice University)

http://news.rice.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/Magma-3-web.jpg

Rice University geologist Rajdeep Dasgupta uses powerful hydraulic presses to crush rock samples in pressures that simulate those found deep inside the Earth. New research by Dasgupta and his colleagues revealed that magma can form much deeper in the planet's mantle than previously thought. (Credit: Jeff Fitlow/Rice University)

http://news.rice.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/Magma-4-web.jpg

A Rice University laboratory led new research detailed in Nature that places magma formation as deep as 250 kilometers. Rice authors are, from left, Rajdeep Dasgupta, an assistant professor of Earth science; graduate student Ananya Mallik and postdoctoral researcher Kyusei Tsuno. (Credit: Jeff Fitlow/Rice University)

Magma in mantle has deep impact

Rice University study suggests rocks melt at a greater depth than once thought

2013-01-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

After decades of research, scientists unlock how insulin interacts with cells

2013-01-10

The discovery of insulin nearly a century ago changed diabetes from a death sentence to a chronic disease.

Today a team that includes researchers from Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine announced a discovery that could lead to dramatic improvements in the lives of people managing diabetes.

After decades of speculation about exactly how insulin interacts with cells, the international group of scientists finally found a definitive answer: in an article published today in the journal Nature, the group describes how insulin binds to the cell to allow the ...

GW researchers find variation in foot strike patterns in predominantly barefoot runners

2013-01-10

WASHINGTON –A recently published paper by two George Washington University researchers shows that the running foot strike patterns vary among habitually barefoot people in Kenya due to speed and other factors such as running habits and the hardness of the ground. These results are counter to the belief that barefoot people prefer one specific style of running.

Kevin Hatala, a Ph.D. student in the Hominid Paleobiology doctoral program at George Washington, is the lead author of the paper that appears in the recent edition of the journal Public Library of Science, or PLOS ...

A history lesson from genes

2013-01-10

When Charles Darwin first sketched how species evolved by natural selection, he drew what looked like a tree. The diagram started at a central point with a common ancestor, then the lines spread apart as organisms evolved and separated into distinct species.

In the 175 years since, scientists have come to agree that Darwin's original drawing is a bit simplistic, given that multiple species mix and interbreed in ways he didn't consider possible (though you can't fault the guy for not getting the most important scientific theory of all time exactly right the first time). ...

Study examines how news spreads on Twitter

2013-01-10

Nearly every major news organization has a Twitter account these days, but just how effective is the microblogging website at spreading news? That's the question University of Arizona professor Sudha Ram set out to answer in a recent study of a dozen major news organizations that use the social media website as one tool for sharing their content.

The answer, according to Ram's research, varies widely by news agency, and there may not be one universally applicable strategy for maximizing Twitter effectiveness. However, news agencies can learn a lot by looking at how their ...

Unnecessary antimicrobial use increases risk of recurrent infectious diarrhea

2013-01-10

The impact of antibiotic misuse has far-reaching consequences in healthcare, including reduced efficacy of the drugs, increased prevalence of drug-resistant organisms, and increased risk of deadly infections. A new study featured in the February issue of Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, the journal of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, found that many patients with Clostridium difficile infection (C. difficile) are prescribed unnecessary antibiotics, increasing their risk of recurrence of the deadly infection. The retrospective report shows ...

Flooding preparedness needs to include infection prevention and control strategies

2013-01-10

Flooding can cause clinical and economic damage to a healthcare facility, but reopening a facility after extensive flooding requires infection prevention and control preparedness plans to ensure a safe environment for patients and healthcare workers. In a study published in the February issue of Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, the journal of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, clinical investigators report key findings and recommendations related to the closure and re-opening of hospitals impacted by black-water floods. The guidance builds on ...

Faulty behavior

2013-01-10

PASADENA, Calif.—In an earthquake, ground motion is the result of waves emitted when the two sides of a fault move—or slip—rapidly past each other, with an average relative speed of about three feet per second. Not all fault segments move so quickly, however—some slip slowly, through a process called creep, and are considered to be "stable," or not capable of hosting rapid earthquake-producing slip. One common hypothesis suggests that such creeping fault behavior is persistent over time, with currently stable segments acting as barriers to fast-slipping, shake-producing ...

Next-generation adaptive optics brings remarkable details to light in stellar nursery

2013-01-10

A new image released today reveals how Gemini Observatory's most advanced adaptive optics (AO) system will help astronomers study the universe with an unprecedented level of clarity and detail by removing distortions due to the Earth's atmosphere. The photo, featuring an area on the outskirts of the famous Orion Nebula, illustrates the instrument's significant advancements over previous-generation AO systems.

"The combination of a constellation of five laser guide stars with multiple deformable mirrors allows us to expand significantly on what has previously been possible ...

Microscopic blood in urine unreliable indicator of urinary tract cancer

2013-01-10

Rochester, MN, January 9, 2013 – Microscopic amounts of blood in urine have been considered a risk factor for urinary tract malignant tumors. However, only a small proportion of patients referred for investigation are subsequently found to have cancer. A new Kaiser Permanente Southern California study published in the February Mayo Clinic Proceedings reports on the development and testing of a Hematuria Risk Index to predict cancer risk. This could potentially lead to significant reductions in the number of unnecessary evaluations.

Individuals with microscopic hematuria ...

Small price differences can make options seem more similar, easing our buying decisions

2013-01-10

Some retailers, such as Apple's iTunes, are known for using uniform pricing in an effort to simplify consumers' choices and perhaps increase their tendency to make impulse purchases. But other stores, like supermarkets, often have small price differences across product flavors and brands.

As counterintuitive as it might seem, these small price differences may actually make the options seem more similar, according to new research published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science. The research shows that adding small differences ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

Robotic wing inspired by nature delivers leap in underwater stability

A clinical reveals that aniridia causes a progressive loss of corneal sensitivity

Fossil amber reveals the secret lives of Cretaceous ants

[Press-News.org] Magma in mantle has deep impactRice University study suggests rocks melt at a greater depth than once thought