(Press-News.org) Muscular dystrophy is caused by the largest human gene, a complex chemical leviathan that has confounded scientists for decades. Research conducted at the University of Missouri and described this month in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences has identified significant sections of the gene that could provide hope to young patients and families.

MU scientists Dongsheng Duan, PhD, and Yi Lai, PhD, identified a sequence in the dystrophin gene that is essential for helping muscle tissues function, a breakthrough discovery that could lead to treatments for the deadly hereditary disease. The MU researchers "found the proverbial needle in a haystack," according to Scott Harper, PhD, a muscular dystrophy expert at The Ohio State University who is not involved in the study.

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), predominantly affecting males, is the most common type of muscular dystrophy. Children with DMD face a future of rapidly weakening muscles, which usually leads to death by respiratory or cardiac failure before their 30th birthday.

Patients with DMD have a gene mutation that disrupts the production of dystrophin, a protein essential for muscle cell survival and function. Absence of dystrophin starts a chain reaction that eventually leads to muscle cell degeneration and death. While dystrophin is vital for muscle development, the protein also needs several "helpers" to maintain the muscle tissue. One of these "helper" molecular compounds is nNOS, which produces nitric oxide that can keep muscle cells healthy during exercise.

"Dystrophin not only helps build muscle cells, it's also a key factor to attracting nNOS to the muscle cell membrane, which is important during exercise," Lai said. "Prior to this discovery, we didn't know how dystrophin made nNOS bind to the cell membrane. What we found was that dystrophin has a special 'claw' that is used to grab nNOS and bring it to the muscle cell membrane. Now that we have that key, we hope to begin the process of developing a therapy for patients."

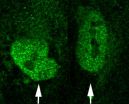

Duan and Lai, scientists with MU's Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology, found that two particular sections of the dystrophin gene must be present for nNOS to bind to the muscle cell membrane. The sections of the gene, known as "repeaters 16 & 17," contain a "claw" that can grab nNOS and bring it to the muscle cell membrane so that it will prevent ischemic damage from muscle activity. Without this "claw," nNOS doesn't bind to the cell membrane and the muscle cells are damaged, leading to further problems associated with muscular dystrophy.

The other key to this puzzle is dystrophin. If the protein is not present in the body, no "claw" exists and nNOS would never make it to the muscle cell membrane. For years, scientists have been attempting to find ways to make the body manufacture dystrophin, and thus get nNOS to the muscle cell membrane. Duan and Lai said the answer might lie elsewhere.

"Everybody, including those individuals with muscular dystrophy, has another protein known as 'utrophin,' " said Duan, a Margaret Proctor Mulligan Distinguished Professor in Medical Research at MU. "Utrophin is nearly identical to dystrophin except that it is missing repeaters 16 & 17, so it cannot attract nNOS to the muscle cell membrane. In our study, we were able to modify utrophin so that it had the repeaters, and thus, the ability to grab nNOS and bring it to the muscle cell membrane to protect muscle. Our study was completed in mice, but if we can do the same thing in larger animals, we could eventually have a therapy for humans with this devastating disease."

Harper described the MU research as "as an exquisite example of a basic study with potentially important translational implications for therapy of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. … The data from the Duan laboratory, reported in this paper and previous studies, demonstrates that the structural elements required for proper nNOS localization should be included in any DMD therapy for which dystrophin restoration is the goal."

For more than 10 years, Duan has been a leader in muscular dystrophy, gene therapy and biology research at MU. In addition to his recently published study in PNAS, Duan's lab continues to examine the basic scientific mechanisms behind muscular dystrophy as well as strategies for treating the disease. For example, his lab is studying the effectiveness of a gene therapy for treating heart failure associated with Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

Using viruses as a means for delivering gene therapy, Duan is also testing how synthetic microgenes could improve muscle function in dystrophic dog and mouse models. In 2011, he and Lai were granted a patent for a synthetic microgene developed in his lab that has now proved to enhance muscle function in dogs. Those results were also published this month in the journal Molecular Therapy.

INFORMATION:

Research in Duan's laboratory is funded by the National Institutes of Health, Muscular Dystrophy Association, Jesse's Journey - The Foundation for Gene and Cell Therapy, Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy, and the University of Missouri.

Scientists discover 'needle in a haystack' for muscular dystrophy patients

Research on significant genetic sequence could lead to treatments for deadly hereditary disease

2013-01-23

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

NASA sees Tropical Cyclone Oswald weaken over Queensland's Cape York Peninsula

2013-01-23

NASA's Aqua satellite documented the formation of Tropical Storm Oswald in the Gulf of Carpentaria on Jan. 21 and the landfall on Jan. 22 in the southwestern Cape York Peninsula of Queenstown, Australia. Oswald has since become remnant low pressure area over land.

Tropical Storm Oswald was hugging the southwestern coast of the Cape York Peninsula, Queensland, Australia when NASA's Aqua satellite first flew overhead on Jan. 21 at 0430 UTC (Jan. 20 at 11:30 p.m. EST). The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instrument aboard NASA's Aqua satellite captured ...

Bacterial supplement could help young pigs fight disease

2013-01-23

Jan. 22, 2013 - A common type of bacteria may help pigs stay healthy during weaning.

In a study of 36 weanling-age pigs, researchers found that a dose of lipid-producing Rhodococcus opacus bacteria increased circulating triglycerides. Triglycerides are a crucial source of energy for the immune system.

"We could potentially strengthen the immune system by providing this bacterium to animals at a stage when they are in need of additional energy," said Janet Donaldson, assistant professor in Biological Sciences Mississippi State University. "By providing an alternative ...

Novel gene-searching software improves accuracy in disease studies

2013-01-23

A novel software tool, developed at The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, streamlines the detection of disease-causing genetic changes through more sensitive detection methods and by automatically correcting for variations that reduce the accuracy of results in conventional software. The software, called ParseCNV, is freely available to the scientific-academic community, and significantly advances the identification of gene variants associated with genetic diseases.

"The algorithm we developed detects copy number variation associations with a higher level of accuracy ...

Disease outbreaks trackable with Twitter

2013-01-23

This flu season you've probably seen a number of friends on social media talking about symptoms.

New research from Brigham Young University says such posts on Twitter could actually be helpful to health officials looking for a head start on outbreaks.

The study sampled 24 million tweets from 10 million unique users. They determined that accurate location information is available for about 15 percent of tweets (gathered from user profiles and tweets that contain GPS data). That's likely a critical mass for an early-warning system that could monitor terms like "fever," ...

Gay African-American youth face unique challenges coming out to families

2013-01-23

NEW BRUNSWICK, N.J. – Coming out to one's family can be stressful, but gay black males face a unique set of personal, familial and social challenges.

"Parents and youths alike worry that gay men cannot meet the rigid expectations of exaggerated masculinity maintained by their families and communities," says Michael C. LaSala, director of the Master of Social Work program at Rutgers University School of Social Work. LaSala, an associate professor, recently completed an exploratory study of African American gay youth and their families from urban neighborhoods in New York ...

Stem cell research helps to identify origins of schizophrenia

2013-01-23

BUFFALO, N.Y. – New University at Buffalo research demonstrates how defects in an important neurological pathway in early development may be responsible for the onset of schizophrenia later in life.

The UB findings, published in Schizophrenia Research (paper at http://bit.ly/Wq1i41), test the hypothesis in a new mouse model of schizophrenia that demonstrates how gestational brain changes cause behavioral problems later in life – just like the human disease.

Partial funding for the research came from New York Stem Cell Science (NYSTEM).

The genomic pathway, called the ...

Black patients with hypertension not prescribed diuretics enough

2013-01-23

NEW YORK (January 22, 2013) -- A research study of more than 600 black patients with uncontrolled hypertension found that less than half were prescribed a diuretic drug with proven benefit that costs just pennies a day, report researchers at Weill Cornell Medical College and the Visiting Nurse Service of New York's (VNSNY) Center for Home Care Policy and Research. The researchers say these new findings should be taken as a serious wake-up call for physicians who treat black patients with hypertension.

Their study, reported in the American Journal of Hypertension, found ...

2013 Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium reveals new advances for GI cancers

2013-01-23

ALEXANDRIA, Va. – New research into the treatment and prognosis of gastrointestinal cancers was released today in advance of the tenth annual Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium being held January 24-26, 2013, at The Moscone West Building in San Francisco, CA.

Five important studies were highlighted today in a live presscast:

Postoperative Treatment with S-1 Chemotherapy Reduces Relapses and Extends Survival in Patients with Pancreatic Cancer: Early results from a Phase III clinical trial conducted in Japan show patients who received the chemotherapy drug S-1 after ...

UT MD Anderson scientists find protein that reins in runaway network

2013-01-23

HOUSTON — Marked for death with molecular tags that act like a homing signal for a cell's protein-destroying machinery, a pivotal enzyme is rescued by another molecule that sweeps the telltale targets off in the nick of time.

The enzyme, called TRAF3, lives on to control a molecular network that's implicated in a variety of immune system-related diseases if left to its own devices.

The University of Texas MD Anderson scientists identified TRAF3's savior and demonstrated how it works in a paper published online Sunday in Nature.

By discovering the role of OTUD7B as ...

NYUCN's Drs. Shedlin and Anastasi publish in the Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care

2013-01-23

New York University College of Nursing (NYUCN) researchers Michele G. Shedlin, PhD, and Joyce K. Anastasi, PhD, DrNP, FAAN, LAc, published a paper, "Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicines and Supplements by Mexican-Origin Patients in a U.S.–Mexico Border HIV Clinic," in the on-line version of the Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care.

Complementary and alternative medicines (CAM) and therapies are often used to improve or maintain overall health and to relieve the side effects of conventional treatments or symptoms associated with chronic illnesses ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Bison hunters abandoned long-used site 1,100 years ago to adapt to changing climate

Parents of children with medical complexity report major challenges with at-home medical devices

The nonlinear Hall effect induced by electrochemical intercalation in MoS2 thin flake devices

Moving beyond money to measure the true value of Earth science information

Engineered moths could replace mice in research into “one of the biggest threats to human health”

Can medical AI lie? Large study maps how LLMs handle health misinformation

The Lancet: People with obesity at 70% higher risk of serious infection with one in ten infectious disease deaths globally potentially linked to obesity, study suggests

Obesity linked to one in 10 infection deaths globally

Legalization of cannabis + retail sales linked to rise in its use and co-use of tobacco

Porpoises ‘buzz’ less when boats are nearby

When heat flows backwards: A neat solution for hydrodynamic heat transport

Firearm injury survivors face long-term health challenges

Columbia Engineering announces new program: Master of Science in Artificial Intelligence

Global collaboration launches streamlined-access to Shank3 cKO research model

Can the digital economy save our lungs and the planet?

Researchers use machine learning to design next generation cooling fluids for electronics and energy systems

Scientists propose new framework to track and manage hidden risks of industrial chemicals across their life cycle

Physicians are not providers: New ACP paper says names in health care have ethical significance

Breakthrough University of Cincinnati study sheds light on survival of new neurons in adult brain

UW researchers use satellite data to quantify methane loss in the stratosphere

Climate change could halve areas suitable for cattle, sheep and goat farming by 2100

Building blocks of life discovered in Bennu asteroid rewrite origin story

Engineered immune cells help reduce toxic proteins in the brain

Novel materials design approach achieves a giant cooling effect and excellent durability in magnetic refrigeration materials

PBM markets for Medicare Part D or Medicaid are highly concentrated in nearly every state

Baycrest study reveals how imagery styles shape pathways into STEM and why gender gaps persist

Decades later, brain training lowers dementia risk

Adrienne Sponberg named executive director of the Ecological Society of America

Cells in the ear that may be crucial for balance

Exploring why some children struggle to learn math

[Press-News.org] Scientists discover 'needle in a haystack' for muscular dystrophy patientsResearch on significant genetic sequence could lead to treatments for deadly hereditary disease