(Press-News.org) Boston, MA—Most weight-loss plans center around a balance between caloric intake and energy expenditure. However, new research has shed light on a new factor that is necessary to shed pounds: timing. Researchers from Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH), in collaboration with the University of Murcia and Tufts University, have found that it's not simply what you eat, but also when you eat, that may help with weight-loss regulation.

The study will be published on January 29, 2013 in the International Journal of Obesity.

"This is the first large-scale prospective study to demonstrate that the timing of meals predicts weight-loss effectiveness," said Frank Scheer, PhD, MSc, director of the Medical Chronobiology Program and associate neuroscientist at BWH, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, and senior author on this study. "Our results indicate that late eaters displayed a slower weight-loss rate and lost significantly less weight than early eaters, suggesting that the timing of large meals could be an important factor in a weight loss program."

To evaluate the role of food timing in weight-loss effectiveness, the researchers studied 420 overweight study participants who followed a 20-week weight-loss treatment program in Spain. The participants were divided into two groups: early-eaters and late-eaters, according to the self-selected timing of the main meal, which in this Mediterranean population was lunch. During this meal, 40 percent of the total daily calories are consumed. Early-eaters ate lunch anytime before 3 p.m. and late-eaters, after 3 p.m. They found that late-eaters lost significantly less weight than early-eaters, and displayed a much slower rate of weight-loss. Late-eaters also had a lower estimated insulin sensitivity, a risk factor for diabetes.

Researchers found that timing of the other (smaller) meals did not play a role in the success of weight loss. However, the late eaters—who lost less weight—also consumed fewer calories during breakfast and were more likely to skip breakfast altogether. Late-eaters also had a lower estimated insulin sensitivity, a risk factor for diabetes.

The researchers also examined other traditional factors that play a role in weight loss such as total calorie intake and expenditure, appetite hormones leptin and ghrelin, and sleep duration. Among these factors, researchers found no differences between both groups, suggesting that the timing of the meal was an important and independent factor in weight loss success.

"This study emphasizes that the timing of food intake itself may play a significant role in weight regulation" explains Marta Garaulet, PhD, professor of Physiology at the University of Murcia Spain, and lead author of the study. "Novel therapeutic strategies should incorporate not only the caloric intake and macronutrient distribution, as it is classically done, but also the timing of food."

###This research was supported by grants from Tomás Pascual and Pilar Gómez-Cuétara Foundations, Spanish Government of Science and Innovation (BFU2011-24720), Séneca Foundation from the Government of Murcia (15123/PI/10). National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants HL-54776, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Grant Number DK075030 and by contracts 53-K06-5-10 and 58-1950-9-001 from the US Department of Agriculture Research, and by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant R01 HL094806, and by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, grant R21 DK089378.

Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) is a 793-bed nonprofit teaching affiliate of Harvard Medical School and a founding member of Partners HealthCare. BWH has more than 3.5 million annual patient visits, is the largest birthing center in New England and employs nearly 15,000 people. The Brigham's medical preeminence dates back to 1832, and today that rich history in clinical care is coupled with its national leadership in patient care, quality improvement and patient safety initiatives, and its dedication to research, innovation, community engagement and educating and training the next generation of health care professionals. Through investigation and discovery conducted at its Biomedical Research Institute (BRI), BWH is an international leader in basic, clinical and translational research on human diseases, involving nearly 1,000 physician-investigators and renowned biomedical scientists and faculty supported by nearly $625 million in funding. BWH continually pushes the boundaries of medicine, including building on its legacy in organ transplantation by performing the first face transplants in the U.S. in 2011. BWH is also home to major landmark epidemiologic population studies, including the Nurses' and Physicians' Health Studies, OurGenes and the Women's Health Initiative. For more information and resources, please visit BWH's online newsroom.

Could the timing of when you eat, be just as important as what you eat?

This is the first large-scale prospective study to demonstrate that the timing of meals predicts weight-loss effectiveness

2013-01-29

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Debunking the 'July effect': Surgery date has little impact on outcome, Mayo Clinic finds

2013-01-29

ROCHESTER, Minn. -- The "July Effect" -- the notion that the influx of new residents and fellows at teaching hospitals each July makes that the worse time of year to be a patient -- seems to be a myth, according to new Mayo Clinic research that examined nearly 1 million hospitalizations for patients undergoing spine surgery from 2001 to 2008. Among those going under the knife, researchers discovered that the month surgery occurred had an insignificant impact on patient outcomes.

In addition, no substantial "July Effect" was observed in higher-risk patients, those admitted ...

Physicians' brain scans indicate doctors can feel their patients' pain -- and their relief

2013-01-29

BOSTON – A patient's relationship with his or her doctor has long been considered an important component of healing. Now, in a novel investigation in which physicians underwent brain scans while they believed they were actually treating patients, researchers have provided the first scientific evidence indicating that doctors truly can feel their patients' pain – and can also experience their relief following treatment.

Led by researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and the Program in Placebo Studies and Therapeutic Encounter (PiPS) at Beth Israel Deaconess ...

Preclinical study identifies 'master' proto-oncogene that regulates ovarian cancer metastasis

2013-01-29

Scientists at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center have discovered the signaling pathway whereby a master regulator of cancer cell proteins – known as Src – leads to ovarian cancer progression when exposed to stress hormones. The researchers report in the current issue of Nature Communications that beta blocker drugs mitigate this effect and reduce cancer deaths by an average of 17 percent.

Src (pronounced "sarc," short for sarcoma) is a proto-oncogene – a normal gene that can become an oncogene due to increased expression – involved in the regulation of ...

Medical societies unite on patient-centered measures for nonsurgical stroke interventions

2013-01-29

FAIRFAX, Va.—The first outcome-based guidelines for interventional treatment of acute ischemic stroke—providing recommendations for rapid treatment—will benefit individuals suffering from brain attacks, often caused by artery-blocking blood clots. Representatives from the Society of Interventional Radiology and seven other medical societies created a multispecialty and international consensus on the metrics and benchmarks for processes of care and technical and clinical outcomes for stroke patients.

In February, the guidelines will be published first in SIR's Journal ...

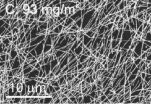

New options for transparent contact electrodes

2013-01-29

This press release is available in German.

Found in flat screens, solar modules, or in new organic light-emitting diode (LED) displays, transparent electrodes have become ubiquitous. Typically, they consist of metal oxides like In2O3, SnO2, ZnO and TiO2.

But since raw materials like indium are becoming more and more costly, researchers have begun to look elsewhere for alternatives. A new review article by HZB scientist Dr. Klaus Ellmer, published in the renowned scientific journal Nature Photonics, is hoping to shed light on the different advantages and disadvantages ...

Epigenetic control of cardiogenesis

2013-01-29

This press release is available in German.

Many different tissues and organs form from pluripotent stem cells during embryonic development. To date it had been known that these processes are controlled by transcription factors for specific tissues. Scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics in Berlin, in collaboration with colleagues at MIT and the Broad Institute in Boston, have now been able to demonstrate that RNA molecules, which do not act as templates for protein synthesis, participate in these processes as well. The scientists knocked down ...

New insights into conquering influenza

2013-01-29

As influenza spreads through the northern hemisphere winter, Dr Linda Wakim and her colleagues in the Laboratory of Professor Jose Villadangos from the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, and the Department of Microbiology and Immunology, believe they have a new clue to why some people fight infections better than others.

The lab has been investigating the 'defensive devices' contained within the T- cells that are located on exposed body surfaces such as skin and mucosal surfaces to ward off infection. T-cells detect cells infected with viruses and kill ...

Survival of the prettiest: Sexual selection can be inferred from the fossil record

2013-01-29

Detecting sexual selection in the fossil record is not impossible, according to scientists writing in Trends in Ecology and Evolution this month, co-authored by Dr Darren Naish of the University of Southampton.

The term "sexual selection" refers to the evolutionary pressures that relate to a species' ability to repel rivals, meet mates and pass on genes. We can observe these processes happening in living animals but how do palaeontologists know that sexual selection operated in fossil ones?

Historically, palaeontologists have thought it challenging, even impossible, ...

New insights into managing our water resources

2013-01-29

Dr Tim Peterson, from the School of Engineering at the University of Melbourne has offered new theories that will lead to a deeper knowledge of how water catchments behave during wet and dry years. His research was published recently in the leading international hydrology journal "Water Resources Research" and was selected by the American Geophysical Union as a highlight of the society's 13 international journals.

Dr Peterson's work shows that some catchments have a finite resilience to wet and dry years because they have two steady states. The traditionally held view ...

Study reveals 2-fold higher incidence of non-melanoma skin cancers for HIV patients

2013-01-29

OAKLAND, Calif., January 29 — HIV-positive patients have a higher incidence of non-melanoma skin cancers, according to a Kaiser Permanente study that appears in the current online issue of the Journal of the National Cancer Institute. Specifically, basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas occur more than twice as often among HIV-positive individuals compared to those who are HIV-negative.

The study cohort of 6,560 HIV-positive and almost 37,000 HIV-negative subjects was drawn from members of Kaiser Permanente Northern California from 1996 to 2008.

Overall, HIV-positive ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Governing with AI: a new AI implementation blueprint for policymakers

Recent pandemic viruses jumped to humans without prior adaptation, UC San Diego study finds

Exercise triggers memory-related brain 'ripples' in humans, researchers report

Increased risk of bullying in open-plan offices

Frequent scrolling affects perceptions of the work environment

Brain activity reveals how well we mentally size up others

Taiwanese and UK scientists identify FOXJ3 gene linked to drug-resistant focal epilepsy

Pregnancy complications impact women’s stress levels and cardiovascular risk long after delivery

Spring fatigue cannot be empirically proven

Do prostate cancer drugs interact with certain anticoagulants to increase bleeding and clotting risks?

Many patients want to talk about their faith. Neurologists often don't know how.

AI disclosure labels may do more harm than good

The ultra-high-energy neutrino may have begun its journey in blazars

Doubling of new prescriptions for ADHD medications among adults since start of COVID-19 pandemic

“Peculiar” ancient ancestor of the crocodile started life on four legs in adolescence before it began walking on two

AI can predict risk of serious heart disease from mammograms

New ultra-low-cost technique could slash the price of soft robotics

Increased connectivity in early Alzheimer’s is lowered by cancer drug in the lab

Study highlights stroke risk linked to recreational drugs, including among young users

Modeling brain aging and resilience over the lifespan reveals new individual factors

ESC launches guidelines for patients to empower women with cardiovascular disease to make informed pregnancy health decisions

Towards tailor-made heat expansion-free materials for precision technology

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

[Press-News.org] Could the timing of when you eat, be just as important as what you eat?This is the first large-scale prospective study to demonstrate that the timing of meals predicts weight-loss effectiveness