(Press-News.org) ITHACA, N.Y. – By simulating 25,000 generations of evolution within computers, Cornell University engineering and robotics researchers have discovered why biological networks tend to be organized as modules – a finding that will lead to a deeper understanding of the evolution of complexity. (Proceedings of the Royal Society, Jan. 30, 2013.)

The new insight also will help evolve artificial intelligence, so robot brains can acquire the grace and cunning of animals.

From brains to gene regulatory networks, many biological entities are organized into modules – dense clusters of interconnected parts within a complex network. For decades biologists have wanted to know why humans, bacteria and other organisms evolved in a modular fashion. Like engineers, nature builds things modularly by building and combining distinct parts, but that does not explain how such modularity evolved in the first place. Renowned biologists Richard Dawkins, Günter P. Wagner, and the late Stephen Jay Gould identified the question of modularity as central to the debate over "the evolution of complexity."

For years, the prevailing assumption was simply that modules evolved because entities that were modular could respond to change more quickly, and therefore had an adaptive advantage over their non-modular competitors. But that may not be enough to explain the origin of the phenomena.

The team discovered that evolution produces modules not because they produce more adaptable designs, but because modular designs have fewer and shorter network connections, which are costly to build and maintain. As it turned out, it was enough to include a "cost of wiring" to make evolution favor modular architectures.

This theory is detailed in "The Evolutionary Origins of Modularity," published today in the Proceedings of the Royal Society by Hod Lipson, Cornell associate professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering; Jean-Baptiste Mouret, a robotics and computer science professor at Université Pierre et Marie Curie in Paris; and by Jeff Clune, a former visiting scientist at Cornell and currently an assistant professor of computer science at the University of Wyoming.

To test the theory, the researchers simulated the evolution of networks with and without a cost for network connections.

"Once you add a cost for network connections, modules immediately appear. Without a cost, modules never form. The effect is quite dramatic," says Clune.

The results may help explain the near-universal presence of modularity in biological networks as diverse as neural networks – such as animal brains – and vascular networks, gene regulatory networks, protein-protein interaction networks, metabolic networks and even human-constructed networks such as the Internet.

"Being able to evolve modularity will let us create more complex, sophisticated computational brains," says Clune.

Says Lipson: "We've had various attempts to try to crack the modularity question in lots of different ways. This one by far is the simplest and most elegant."

###

The National Science Foundation and the French National Research Agency funded this research.

Cornell engineers solve a biological mystery and boost artificial intelligence

2013-01-30

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Going trayless study shows student impact

2013-01-30

If you need any evidence of the impact of student research on life at American University's campus, look no further than something that's missing.

Trays.

Following a 2009 study at American University's main dining hall that showed a significant reduction in food waste and dishes used when trays were removed, trays have mostly gone the way of beanies and sock hops.

Now, for the first time, a new paper coauthored by AU professor Kiho Kim and AU environmental studies graduate Stevia Morawski, provides hard evidence of big energy savings as well as a 32 percent reduction ...

Scripps Research Institute study shows how brain cells shape temperature preferences

2013-01-30

JUPITER, FL, January 29, 2013 – While the wooly musk ox may like it cold, fruit flies definitely do not. They like it hot, or at least warm. In fact, their preferred optimum temperature is very similar to that of humans—76 degrees F.

Scientists have known that a type of brain cell circuit helps regulate a variety of innate and learned behavior in animals, including their temperature preferences. What has been a mystery is whether or not this behavior stems from a specific set of neurons (brain cells) or overlapping sets.

Now, a new study from The Scripps Research Institute ...

Mistrust of government often deters older adults from HIV testing

2013-01-30

One out of every four people living with HIV/AIDS is 50 or older, yet these older individuals are far more likely to be diagnosed when they are already in the later stages of infection. Such late diagnoses put their health, and the health of others, at greater risk than would have been the case with earlier detection.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 43 percent of HIV-positive people between the ages of 50 and 55, and 51 percent of those 65 or older, develop full-blown AIDS within a year of their diagnosis, and these older adults account ...

'Super' enzyme protects against dangers of oxygen

2013-01-30

Just like a comic book super hero, you could say that the enzyme superoxide dismutase (SOD1) has a secret identity. Since its discovery in 1969, scientists believed SOD1's only role was to protect living cells against damage from free radicals. Now, researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health have discovered that SOD1 protects cells by regulating cell energy and metabolism. The results of their research were published January 17, 2013, in the journal Cell.

Transforming oxygen to energy for growth is key to life for all living cells, which happens ...

Spring may come earlier to North American forests

2013-01-30

Trees in the continental U.S. could send out new spring leaves up to 17 days earlier in the coming century than they did before global temperatures started to rise, according to a new study by Princeton University researchers. These climate-driven changes could lead to changes in the composition of northeastern forests and give a boost to their ability to take up carbon dioxide.

Trees play an important role in taking up carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, so researchers led by David Medvigy, assistant professor in Princeton's department of geosciences, wanted to evaluate ...

Low-income pregnant women in rural areas experience high levels of stress, researcher says

2013-01-30

COLUMBIA, Mo. – Stress during pregnancy puts mothers' and their babies' health at risk, previous research has shown. Now, a University of Missouri study indicates low-income pregnant women in rural areas experience high levels of stress yet lack appropriate means to manage their emotional and physical well-being. Health providers should serve as facilitators and link rural women with resources.

"Many people think of rural life as being idyllic and peaceful, but, in truth, there are a lot of health disparities for residents of rural communities," said Tina Bloom, assistant ...

Professional training 'in the wild' overrides laboratory decision preferences

2013-01-30

Many simulation-based studies have been conducted, and theories developed, about the behaviors of financial market traders. New work by human factors/ergonomics (HF/E) researchers suggests that decision-making research on the behavior of traders conducted "in the wild" (i.e., real-world situations) can offer an alternative lens that extends laboratory insights and provokes new questions.

In their article in the Journal of Cognitive Engineering and Decision Making, "Understanding Preferences in Experience-Based Choice," authors Claire McAndrew (University College London) ...

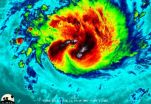

NASA sees some powerful 'overshooting cloud tops' in Cyclone Felleng

2013-01-30

NASA satellite imagery revealed that Cyclone Felleng is packing some powerful thunderstorms with overshooting cloud tops.

An overshooting (cloud) top is a dome-like protrusion that shoots out of the top of the anvil of a thunderstorm and into the troposphere. It takes a lot of energy and uplift in a storm to create an overshooting top, because usually vertical cloud growth stops at the tropopause and clouds spread horizontally, forming an "anvil" shape on top of the thunderstorms.

During the night-time hours (Madagascar local time) of Jan. 28, NASA-NOAA's Suomi NPP ...

Study: Husbands who do more traditionally female housework have less sex

2013-01-30

WASHINGTON, DC, January 24, 2013 — Married men who spend more time doing traditionally female household tasks—including cooking, cleaning, and shopping—report having less sex than husbands who don't do as much, according to a new study in the February issue of the American Sociological Review.

"Our findings suggest the importance of socialized gender roles for sexual frequency in heterosexual marriage," said Sabino Kornrich, the study's lead author and a junior researcher at the Center for Advanced Studies at the Juan March Institute in Madrid. "Couples in which men participate ...

More sex for married couples with traditional divisions of housework

2013-01-30

Married men and women who divide household chores in traditional ways report having more sex than couples who share so-called men's and women's work, according to a new study co-authored by sociologists at the University of Washington.

Other studies have found that husbands got more sex if they did more housework, implying that sex was in exchange for housework. But those studies did not factor in what types of chores the husbands were doing.

The new study, published in the February issue of the journal American Sociological Review, shows that sex isn't a bargaining ...