(Press-News.org) (Embargoed) CHAPEL HILL, N.C. – New research in animals triggered by a combination of serendipity and counterintuitive thinking could point the way to treating fractures caused by rapid bone loss in people, including patients with metastatic cancers.

A series of studies at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine found that steroid drugs, known for inducing bone loss with prolonged use, actually help suppress a molecule that's key to the rapid bone loss process. A report of the new findings appears online Feb. 5, 2013 in the journal PLOS ONE.

Osteoporosis or the loss of bone mass is a major public health problem in the Western world and commonly results in hip and spine fractures. "But rib fractures are the most common and yet most unreported osteoporotic fractures and also occur in many cancers such as breast cancer, malignant melanoma, and myelomas, that metastasize and spread to the ribs," says Arjun Deb, MD, assistant professor in the departments of Medicine and Cell Biology and Physiology at UNC.

"While little is known about the biology of rib fractures, we have identified a molecular mechanism that could have important implications for the treatment of fractures in cancers and other conditions often associated with rapid bone loss," adds Deb, who also is a member of UNC's McAllister Heart Institute and Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center.

The UNC researcher indicated that his lab arrived at the study "via serendipity." From stromal cells of adult mice, they had deleted a gene called beta catenin. These cells, also known as fibroblasts, form the connective tissue of almost all organs in the body. The Deb lab was working on the molecular regulation of these cells.

But something "amazing" occurred, he said. Following beta catenin deletion, the mice died within three weeks. The researchers looked at the functioning of every organ – heart, kidney, lung, spleen – wherever this gene could possibly be expressed. All appeared normal, except lung function. "With just a whiff of anesthesia, their blood oxygen saturation dropped precipitously. This was a first clue of a problem in the respiratory system of these animals." But the lungs looked absolutely fine under the microscope.

Deb then turned to UNC's physics & astronomy department, which had developed a novel contactless fiber-optic displacement sensor for monitoring respiration during mouse CT scans. In association with the department of radiology and the Biomedical Research Imaging Center at UNC, 3-D lung reconstruction revealed profound lung collapse on one or both sides. This was a puzzle. "How can an animal with normal lung tissue under a microscope have lung collapse and respiratory problems?" Deb wondered whether the chest wall could be the culprit.

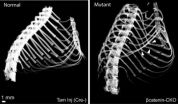

CT scans of the chest wall in these animals revealed multiple spontaneous fractures affecting multiple ribs. The affected ribs had 60-70 percent less bone compared to normal ribs. Essentially the bony rib cage had disappeared within 3 weeks, said Deb, and he immediately realized that the animals were dying from respiratory failure because the frail chest wall was unable to support respiration.

Bone mass is usually maintained by a close functional coupling of osteoblasts (cells that form bone) and osteoclasts (cells that resorb bone). The study team found a huge infiltration of osteoclasts into the animals' ribs. Other bones, including the spine and femur, also showed some resorption but not as dramatic as in the ribs.

And when drugs such as bisphosphonates, commonly used to preserve bone mass in humans were given to the animals, their survival was prolonged only briefly. This led the study team to think that the osteoclast formation was so aggressive that the body was unable to form new bone to keep apace with the bone loss.

In conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and other problems involving inflammation, many types of inflammatory cells promote bone resorption, which led the researchers to see if treatment with corticosteroids might be helpful in these animals. And it was: a 30-40 percent increase in bone mass, compared to animals that did not get steroids. They also found 60-70 percent of the ribs were preserved.

"Notably, 75 percent of the animals survived," Deb said. "And after 80 days, we saw that the ribs showed evidence of repair, they were able to form new bone. And when we looked at new CT lung scans, the lungs were expanded and the ribs contained far less numbers of osteoclasts."

As to mechanism, Deb explains that a molecule in bone called rank ligand (RANKL) is important for osteoclast formation. "We found that steroids were suppressing RANKL to the extent that RANKL levels in these animals were the same as healthy animals."

"From that perspective, these studies are interesting and challenge the existing paradigm: that steroids are drugs that cause bone loss. They do, but in rapid bone loss from aggressive osteoclast overactivity, steroids may be helpful. That's the principle message of this story."

INFORMATION:

Study co-authors were JinZhu Duan, Yueh Lee, Corey Jania, Jucheng Gong, Mauricio Rojas, Laurel Burk, Monte Willis, Jonathon Homeister, Stephen Tilley, and Janet Rubin. The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the Ellison Medical Foundation.

Steroids help reverse rapid bone loss tied to rib fractures

2013-02-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Paternal obesity impacts child's chances of cancer

2013-02-06

Maternal diet and weight can impact their child's health even before birth – but so can a father's, shows a study published in BioMed Central's open access journal BMC Medicine. Hypomethylation of the gene coding for the Insulin-like growth factor 2, (IGF2),in newborns correlates to an increased risk of developing cancer later in life, and, for babies born to obese fathers, there is a decrease in the amount of DNA methylation of IGF2 in foetal cells isolated from cord blood.

As part of the Newborn Epigenetics Study (NEST) at Duke University Hospital, information was collected ...

The number of multiple births affected by congenital anomalies has doubled since the 1980s

2013-02-06

The number of congenital anomalies, or birth defects arising from multiple births has almost doubled since the 1980s, suggests a new study published today (6 February) in BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology.

The study investigates how the change in the proportion of multiple births has affected the prevalence of congenital anomalies from multiple births, and the relative risk of congenital anomaly in multiple versus singleton births.

This study, led by the University of Ulster over a 24-year period (1984 – 2007) across 14 European countries ...

Study raises questions about dietary fats and heart disease guidance

2013-02-06

Dietary advice about fats and the risk of heart disease is called into question on bmj.com today as a clinical trial shows that replacing saturated animal fats with omega-6 polyunsaturated vegetable fats is linked to an increased risk of death among patients with heart disease.

The researchers say their findings could have important implications for worldwide dietary recommendations.

Advice to substitute vegetable oils rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) for animal fats rich in saturated fats to help reduce the risk of heart disease has been a cornerstone of ...

Green tea and red wine extracts interrupt Alzheimer's disease pathway in cells

2013-02-06

Natural chemicals found in green tea and red wine may disrupt a key step of the Alzheimer's disease pathway, according to new research from the University of Leeds.

In early-stage laboratory experiments, the researchers identified the process which allows harmful clumps of protein to latch on to brain cells, causing them to die. They were able to interrupt this pathway using the purified extracts of EGCG from green tea and resveratrol from red wine.

The findings, published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, offer potential new targets for developing drugs to treat ...

Obesity in dads may be associated with offspring's increased risk of disease

2013-02-06

DURHAM, N.C. -- A father's obesity is one factor that may influence his children's health and potentially raise their risk for diseases like cancer, according to new research from Duke Medicine.

The study, which appears Feb. 6 in the journal BMC Medicine, is the first in humans to show that paternal obesity may alter a genetic mechanism in the next generation, suggesting that a father's lifestyle factors may be transmitted to his children.

"Understanding the risks of the current Western lifestyle on future generations is important," said molecular biologist Adelheid ...

Purification on the cheap

2013-02-06

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Increased natural gas production is seen as a crucial step away from the greenhouse gas emissions of coal plants and toward U.S. energy independence. But natural gas wells have problems: Large volumes of deep water, often heavily laden with salts and minerals, flow out along with the gas. That so-called "produced water" must be disposed of, or cleaned.

Now, a process developed by engineers at MIT could solve the problem and produce clean water at relatively low cost. After further development, the process could also lead to inexpensive, efficient desalination ...

Are deaf and hard-of-hearing physicians getting the support they need?

2013-02-06

(SACRAMENTO, Calif.) — Deaf and hard of hearing (DHoH) people must overcome significant professional barriers, particularly in health care professions. A number of accommodations are available for hearing-impaired physicians, such as electronic stethoscopes and closed-captioning technologies, but are these approaches making a difference?

A team of researchers from the University of California, Davis, the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and the University of Michigan surveyed DHoH physicians and medical students to determine whether these and ...

New waterjets could propel LCS to greater speeds

2013-02-06

ARLINGTON, Va. —The Navy's fifth Littoral Combat Ship (LCS), Milwaukee, will be the first to benefit from new high-power density waterjets aimed at staving off rudder and propeller damage experienced on high-speed ships.

The product of an Office of Naval Research (ONR) Future Naval Capabilities (FNC) program, the waterjets arrived last month at the Marinette Marine shipyard in Wisconsin, where Milwaukee (LCS 5) is under construction.

"We believe these waterjets are the future," said Dr. Ki-Han Kim, program manager in ONR's Ship Systems and Engineering Research Division. ...

Study finds potential to match tumors with known cancer drugs

2013-02-06

ANN ARBOR, Mich. — When it comes to gene sequencing and personalized medicine for cancer, spotting an aberrant kinase is a home run. The proteins are relatively easy to target with drugs and plenty of kinase inhibitors already exist.

Now in a new study, University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center researchers assess the complete landscape of a cancer's "kinome" expression and determine which kinases are acting up in a particular tumor. They go on to show that those particular kinases can be targeted with drugs – potentially combining multiple drugs to target multiple ...

New modeling approach transforms imaging technologies

2013-02-06

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. – Researchers are improving the performance of technologies ranging from medical CT scanners to digital cameras using a system of models to extract specific information from huge collections of data and then reconstructing images like a jigsaw puzzle.

The new approach is called model-based iterative reconstruction, or MBIR.

"It's more-or-less how humans solve problems by trial and error, assessing probability and discarding extraneous information," said Charles Bouman, Purdue University's Michael and Katherine Birck Professor of Electrical and Computer ...