(Press-News.org) Research carried out by scientists at the Georgia Institute of Technology and The University of Manchester has revealed new insights into how cells stick to each other and to other bodily structures, an essential function in the formation of tissue structures and organs. It's thought that abnormalities in their ability to do so play an important role in a broad range of disorders, including cardiovascular disease and cancer.

The study's findings are outlined in the journal Molecular Cell and describe a surprising new aspect of cell adhesion involving the family of cell adhesion molecules known as integrins, which are found on the surfaces of most cells. The research uncovered a phenomenon termed "cyclic mechanical reinforcement," in which the length of time during which bonds exist is extended with repeated pulling and release between the integrins and ligands that are part of the extracellular matrix to which the cells attach.

Professor Martin Humphries, dean of the faculty of life sciences at the University of Manchester and one of the paper's co-authors, says the study suggests some new capabilities for cells: "This paper identifies a new kind of bond that is strengthened by cyclical applications of force, and which appears to be mediated by complex shape changes in integrin receptors. The findings also shed light on a possible mechanism used by cells to sense extracellular topography and to aggregate information through 'remembering' multiple interaction events."

The cyclic mechanical reinforcement allows force to prolong the lifetimes of bonds, demonstrating a mechanical regulation of receptor-ligand interactions and identifying a molecular mechanism for strengthening cell adhesion through cyclical forces.

"Many cell functions such as differentiation, growth and the expression of particular genes depend on cell interaction with the ligands of the intracellular matrix," said Cheng Zhu, a professor in the Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory University and the study's corresponding author. "The cells respond to their environment, which includes many mechanical aspects. This study has extended our understanding of how connections are made and how mechanical forces regulate interactions."

The research was published online by the journal on February 14th. The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Wellcome Trust.

Cells of the body regulate adhesion in response to both internally- and externally-applied forces. This is particularly important to adhesion mediated by proteins such as integrins that connect the extracellular matrix to the cytoskeleton – and provide cells with both mechanical anchorages and the means to initiate signaling.

Using delicate force measuring equipment, researchers in Zhu's lab and the laboratory of Andres Garcia – a professor in the Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering at Georgia Tech – collaborated to study adhesion between integrin and fibronectin, a protein component of the extracellular matrix. What they found was that cyclic forces applied to the bond switch it from a short lived state – with lifetimes of about one second – to a long-lived state that can exist for more than a hundred seconds.

"Force can be very important in biology," said Zhu. "Force has direction, magnitude and duration, so in describing its effects on biological systems, you have to use a more complete language."

Zhu, Garcia and Georgia Tech graduate students Fang Kong, William Parks and David Dumbauld – along with postdoctoral fellow Zenhai Li – used two different mechanical techniques to study the strength of bonds between integrin and fibronectin. One technique measured the bond strengths in purified molecules, while the other studied the effects of them in their native cellular environment.

"We have very precise force transducers that allow us to measure force on the scale of pico-newtons," said Zhu. "We prepare the samples in such a way that we engage only one bond, then we control the application of force and observe what happens."

The researchers first used an atomic force microscope to bring the integrin molecule together with the fibronectin, then separate the two. Instruments measured the pico-newton forces required to separate the molecules, and found that the duration of the bonds increased with the repetition of the contacts.

The second technique, known as BFP, involved the use of a fibronectin-bearing glass bead attached to a red blood cell aspirated by a micropipette. Integrin expressed on the micropipette-aspirated cell was pressed into the bead, then pulled away over repeated cycles. Lifetime measurement confirmed that repeated pulling increased the longevity of the bonds.

The researchers studied two integrins, part of a family of 24 related molecules that operate in humans. In future work, they hope to determine whether or not the cyclic mechanical reinforcement they observed is a universal property of many cellular adhesion molecules.

The researchers also hope to explore how cells use this cyclic mechanical reinforcement. Because many disease processes result from abnormal cellular adhesion mechanisms, a better understanding could provide insights into how cardiovascular disease, cancer and immune system disorders operate.

"The findings of the paper have deep implications for our understanding of force-regulated signaling," added Humphries. "There is abundant biological evidence for profound effects of extracellular tensility and elasticity in controlling processes such as cancer cell proliferation and stem cell differentiation, but the mechanisms whereby this information is transduced across the outer cell membrane are unclear."

INFORMATION:

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under grants AI44902 and GM065918. The conclusions are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

CITATION: Kong, F., et al., Cyclic Mechanical Reinforcement of Integrin-Ligand Interactions, Molecular Cell (2013).

Why cells stick: Phenomenon extends longevity of bonds between cells

2013-02-15

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Researchers invent 'acoustic-assisted' magnetic information storage

2013-02-15

CORVALLIS, Ore. – Electrical engineers at Oregon State University have discovered a way to use high- frequency sound waves to enhance the magnetic storage of data, offering a new approach to improve the data storage capabilities of a multitude of electronic devices around the world.

The technology, called acoustic-assisted magnetic recording, has been presented at a professional conference, and a patent application was filed this week.

Magnetic storage of data is one of the most inexpensive and widespread technologies known, found in everything from computer hard drives ...

Leading RSV researcher publishes work at Le Bonheur Children's

2013-02-15

Memphis, Tenn. – Studies at Le Bonheur Children's Hospital in Memphis, Tenn., are advancing our understanding of how viruses, including RSV, replicate in humans, mutate to avoid the immune response and can be effectively treated.

John DeVincenzo, MD, medical director of Molecular Diagnostics and Virology Laboratories at Le Bonheur, and professor of Pediatrics and Microbiology, Immunology, and Molecular Biology at The University of Tennessee Health Science Center, has recently published three papers on this topic. DeVincenzo's lab is one of only two of its kind in the ...

Revealing the secrets of motility in archaea

2013-02-15

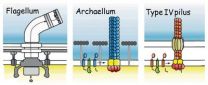

The protein structure of the motor that propels archaea has been characterized for the first time by a team of scientists from the U.S. Department of Energy's Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and Germany's Max Planck Institute (MPI) for Terrestrial Microbiology.

The motility structure of this third domain of life has long been called a flagellum, a whip-like filament that, like the well-studied bacterial flagellum, rotates like a propeller. But although the archaeal structure has a similar function, it is so profoundly different in structure, genetics, ...

APS applauds President Obama's support of R&D in SOTU

2013-02-15

WASHINGTON, D.C. – The American Physical Society (APS), the nation's largest organization of physicists, commends President Obama's exhortation in his State of the Union Speech that, "Now is the time to reach a level of research and development not seen since the height of the Space Race."

During the Space Race, the nation made huge investments in scientific research, which led to new discoveries, accelerated technological advancements and generated new innovations and businesses.

The President also noted that sequestration -- automatic spending cuts scheduled to occur ...

A dual look at photosystem II using the world's most powerful X-ray laser

2013-02-15

From providing living cells with energy, to nitrogen fixation, to the splitting of water molecules, the catalytic activities of metalloenzymes – proteins that contain a metal ion – are vital to life on Earth. A better understanding of the chemistry behind these catalytic activities could pave the way for exciting new technologies, most prominently artificial photosynthesis systems that would provide clean, green and renewable energy. Now, researchers with the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)'s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and the SLAC National Accelerator ...

Noncoding RNAs offer huge therapeutic and diagnostic potential

2013-02-15

New Rochelle, NY, February 14, 2013—As scientists continue to unravel the complexity of the human genome and to uncover vital elements that play a role in both normal physiology and disease, one particular class of elements called noncoding RNAs is gaining a lot of attention. Guest Editor Tom Cech, PhD and Executive Editor Fintan Steele, PhD explore the enormous potential value of this rapidly advancing research area in their Editorial " The (Noncoding) RNA World." The authors introduce a special research section on noncoding RNAs published in the current issue of Nucleic ...

Building healthy bones takes guts

2013-02-15

EAST LANSING, Mich. — In what could be an early step toward new treatments for people with osteoporosis, scientists at Michigan State University report that a natural probiotic supplement can help male mice produce healthier bones.

Interestingly, the same can't be said for female mice, the researchers report in the Journal of Cellular Physiology.

"We know that inflammation in the gut can cause bone loss, though it's unclear exactly why," said lead author Laura McCabe, a professor in MSU's departments of Physiology and Radiology. "The neat thing we found is that a probiotic ...

New methodology to predict pandemics

2013-02-15

NEW YORK – February 13, 2013 – EcoHealth Alliance, the nonprofit organization that focuses on local conservation and global health issues, announced new research focused on the rapid identification of disease outbreaks in the peer reviewed publication, Journal of the Royal Society Interface. The article, authored by leading scientists in the fields of emerging disease ecology, biomathematics, computational biology and bioinformatics, shows how network theory can be used to identify outbreaks of unidentified diseases. The strategy builds on the wealth of online surveillance ...

Quantum cryptography put to work for electric grid security

2013-02-15

LOS ALAMOS, N.M., Feb. 14, 2013—A Los Alamos National Laboratory quantum cryptography (QC) team has successfully completed the first-ever demonstration of securing control data for electric grids using quantum cryptography.

The demonstration was performed in the electric grid test bed that is part of the Trustworthy Cyber Infrastructure for the Power Grid (TCIPG) project at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) that was set up under the Department of Energy's Cyber Security for Energy Delivery Systems program in the Office of Electricity Delivery and Energy ...

A microbial biorefinery provides new insight into how bacteria regulate genes

2013-02-15

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Microorganisms that can break down plant biomass into the precursors of biodiesel or other commodity chemicals might one day be used to produce alternatives to petroleum. But the potential of this "biorefinery" technology is limited by the fact that most microorganisms cannot break down lignin, a highly stable polymer that makes up as much as a third of plant biomass.

Streptomyces bacteria are among few microorganisms known to degrade and consume lignin. Now a group of researchers at Brown University has unlocked the genetic and molecular ...