(Press-News.org) Pathological protein deposits linked to Alzheimer's disease and cerebral amyloid angiopathy can be triggered not only by the administration of pathogenic misfolded protein fragments directly into the brain but also by peripheral administration outside the brain. This is shown in a new study done by researchers at the Hertie Institute of Clinical Brain Research (HIH, University Hospital Tübingen, University of Tübingen) and the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE), to be published in Science on October 21, 2010.

Alzheimer's disease and a brain vascular disorder called cerebral beta-amyloid angiopathy are characterized by the accumulation of a protein fragment known as Abeta. In Alzheimer´s disease, misfolded Abeta is deposited mainly in so-called amyloid plaques, whereas in cerebral beta-amyloid angiopathy, the Abeta protein aggregates in the walls of blood vessels, interfering with their function and, in some cases, causing them to rupture with subsequent intracerebral bleeding.

In 2006, scientists in Tübingen, led by Mathias Jucker, reported that injection of dilute extracts from Alzheimer's disease brain tissue, or from Abeta-laden mouse brain tissue, into the brains of transgenic mice (genetically modified to produce the human form of Abeta) stimulated Abeta aggregation within the mouse brain (Science 313: 1781-4, 2006).

In the current Science study, Professor Jucker and first author Yvonne Eisele, together with their research team (HIH, University of Tübingen,DZNE) and colleagues Matthias Staufenbiel (Novartis), Mathias Heikenwälder (University of Zürich), and Lary Walker (Emory University Atlanta) report that Abeta deposition can be induced in the transgenic mouse brain by the intraperitoneal administration of mouse brain extract containing misfolded Abeta. This induced Abeta deposition was primarily associated with the vasculature, but was also evident as amyloid plaques between nerve cells. The time needed to induce amyloid deposition in the brain was much longer for peripheral as compared to direct brain administration. In both cases, the induced amyloid deposition also triggered several neurodegenerative and neuroinflammatory changes commonly observed in the brains of patients with Alzheimer´s disease and cerebral beta-amyloid angiopathy. "The finding that mechanisms exist allowing for the transport of Abeta aggregates from the periphery to the brain raises the question of whether protein aggregation and propagation, which may also be involved in other neurodegenerative brain diseases, can be induced by agents originating in the periphery", points out Professor Jucker. The present findings provide new clues on pathogenetic mechanisms underlying Alzheimer's disease; further investigation will likely lead to new strategies for prevention and treatment.

While this molecular principle of induced protein aggregation bears similarities to that of prion diseases, the latter, which include bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), can also be initiated by introducing prions at sites peripheral to the brain. The present study shows that this is not a characteristic unique to prion diseases, as has been assumed so far. Despite this remarkable observation and the apparent mechanistic similarities between Alzheimer´s and prion diseases, there is no evidence that Alzheimer's disease or cerebral amyloid angiopathy is transmitted between mammals or humans in the same manner as prion diseases.

INFORMATION:

Title of the original publication:

Peripherally Applied Ab-Containing Inoculates Induce Cerebral b-Amyloidosis

Authors: Yvonne S. Eisele1,2, Ulrike Obermüller1,2, Götz Heilbronner1,2,3, Frank Baumann1,2, Stephan A. Kaeser1,2, Hartwig Wolburg4, Lary C. Walker5, Matthias Staufenbiel6, Mathias Heikenwalder7, Mathias Jucker1,2,*

1Department of Cellular Neurology, Hertie-Institute for Clinical Brain Research, University of Tübingen, D-72076 Tübingen, Germany; 2DZNE - German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases, Tübingen, Germany; 3Graduate School for Cellular and Molecular Neuroscience, University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany; 4Department of Pathology, University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany; 5Yerkes National Primate Research Center and Department of Neurology, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA, 6Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research, Neuroscience Discovery, Basel, Switzerland; 7Department of Pathology, Institute for Neuropathology, University Hospital, Zürich, Switzerland.

Advanced online publication in Science, Science express Website 21 October 2010 (2:00 pm U.S. Eastern Time/ 8 pm Central European Summer Time) www.scienceexpress.org

END

A new type of sound sensor system has been developed to predict the likelihood of a landslide.

Thought to be the first system of its kind in the world, it works by measuring and analysing the acoustic behaviour of soil to establish when a landslide is imminent so preventative action can be taken.

Noise created by movement under the surface builds to a crescendo as the slope becomes unstable and so gauging the increased rate of generated sound enables accurate prediction of a catastrophic soil collapse.

The technique has been developed by researchers at Loughborough ...

Scientists at The University of Nottingham and the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute near Cambridge have pin-pointed the 72 molecular switches that control the three key stages in the life cycle of the malaria parasite and have discovered that over a third of these switches can be disrupted in some way.

Their research which has been funded by Wellcome Trust and the Medical Research Council (MRC) is a significant breakthrough in the search for cheap and effective vaccines and drugs to stop the transmission of a disease which kills up to a million children a year.

Until ...

Power plants that burn fossil fuels remain the main source of electricity generation across the globe. Modern power plants have scrubbers to remove sulfur compounds from their flue gases, which has helped reduce the problem of acid rain. Now, researchers in India have devised a way to convert the waste material produced by the scrubbing process into value-added products. They describe details in the International Journal of Environment and Pollution.

Fossil fuels contain sulfur compounds that are released as sulfur dioxide during combustion. As such, flue gas desulfurisation ...

Researchers from the University of Valencia (UV) have identified the effects of the way parents bring up their children on social structure in Spain. Their conclusions show that punishment, deprivation and strict rules impact on a family's self esteem.

"The objective was to analyse which style of parental socialisation is ideal in Spain by measuring the psychosocial adjustment of children", Fernando García, co-author of the study and a researcher at the UV, tells SINC.

The study, which has been published in the latest issue of the journal Infancia y Aprendizaje, was ...

INDIANAPOLIS – A study published earlier this year in the peer reviewed online journal BMC Public Health has found that residing in a neighborhood with adverse living conditions such as low air quality, loud traffic or industrial noise, or poorly maintained streets, sidewalks and yards, makes mobility problems much more likely in late middle-aged African Americans with diabetes.

"We followed a large group of African Americans for 3 years and found an extremely strong correlation between diabetes and adverse neighborhood conditions. The study participants were between ...

Jena (21 October 2010) Scientists from the Friedrich-Schiller-University Jena (Germany) were successful in improving a fabrication process for Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) probe tips.

Atomic Force Microscopy is able to scan surfaces so that even tiniest nano structures become visible. Knowledge about these structures is for instance important for the development of new materials and carrier systems for active substances. The size of the probe is highly important for the image quality as it limits the dimensions that can be visualized – the smaller the probe, the smaller ...

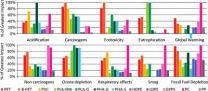

PITTSBURGH—An analysis of plant and petroleum-derived plastics by University of Pittsburgh researchers suggests that biopolymers are not necessarily better for the environment than their petroleum-based relatives, according to a report in Environmental Science & Technology. The Pitt team found that while biopolymers are the more eco-friendly material, traditional plastics can be less environmentally taxing to produce.

Biopolymers trumped the other plastics for biodegradability, low toxicity, and use of renewable resources. Nonetheless, the farming and chemical processing ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- Being the right size and existing in the limbo between a solid and a liquid state appear to be the secrets to improving the efficiency of chemical catalysts that can create better nanoparticles or more efficient energy sources.

When matter is in this transitional state, a catalyst can achieve its utmost potential with the right combination of catalyst particle size and temperature, according to a pair of Duke University researchers. A catalyst is an agent or chemical that facilitates a chemical reaction. It is estimated that more than 90 percent of chemical ...

PITTSBURGH—Computer scientists at Carnegie Mellon University have devised an innovative and elegantly concise algorithm that can efficiently solve systems of linear equations that are critical to such important computer applications as image processing, logistics and scheduling problems, and recommendation systems.

The theoretical breakthrough by Professor Gary Miller, Systems Scientist Ioannis Koutis and Ph.D. student Richard Peng, all of Carnegie Mellon's Computer Science Department, has enormous practical potential. Linear systems are widely used to model real-world ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- Step aside copper and make way for a better carrier of information -- light.

As good as the metal has been in zipping information from one circuit to another on silicon inside computers and other electronic devices, optical signals can carry much more, according to Duke University electrical engineers. So the engineers have designed and demonstrated microscopically small lasers integrated with thin film-light guides on silicon that could replace the copper in a host of electronic products.

The structures on silicon not only contain tiny light-emitting ...