(Press-News.org) CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Bringing the concept of an "artificial leaf" closer to reality, a team of researchers at MIT has published a detailed analysis of all the factors that could limit the efficiency of such a system. The new analysis lays out a roadmap for a research program to improve the efficiency of these systems, and could quickly lead to the production of a practical, inexpensive and commercially viable prototype.

Such a system would use sunlight to produce a storable fuel, such as hydrogen, instead of electricity for immediate use. This fuel could then be used on demand to generate electricity through a fuel cell or other device. This process would liberate solar energy for use when the sun isn't shining, and open up a host of potential new applications.

The new work is described in a paper this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences by associate professor of mechanical engineering Tonio Buonassisi, former MIT professor Daniel Nocera (now at Harvard University), MIT postdoc Mark Winkler (now at IBM) and former MIT graduate student Casandra Cox (now at Harvard). It follows up on 2011 research that produced a "proof of concept" of an artificial leaf — a small device that, when placed in a container of water and exposed to sunlight, would produce bubbles of hydrogen and oxygen.

The device combines two technologies: a standard silicon solar cell, which converts sunlight into electricity, and chemical catalysts applied to each side of the cell. Together, these would create an electrochemical device that uses an electric current to split atoms of hydrogen and oxygen from the water molecules surrounding them.

The goal is to produce an inexpensive, self-contained system that could be built from abundant materials. Nocera has long advocated such devices as a means of bringing electricity to billions of people, mostly in the developing world, who now have little or no access to it.

"What's significant is that this paper really describes all this technology that is known, and what to expect if we put it all together," Cox says. "It points out all the challenges, and then you can experimentally address each challenge separately."

Winkler adds that this is a "pretty robust analysis that looked at what's the best you could do with market-ready technology."

The original demonstration leaf, in 2011, had low efficiencies, converting less than 4.7 percent of sunlight into fuel, Buonassisi says. But the team's new analysis shows that efficiencies of 16 percent or more should now be possible using single-bandgap semiconductors, such as crystalline silicon.

"We were surprised, actually," Winkler says: Conventional wisdom held that the characteristics of silicon solar cells would severely limit their effectiveness in splitting water, but that turned out not to be the case. "You've just got to question the conventional wisdom sometimes," he says.

The key to obtaining high solar-to-fuel efficiencies is to combine the right solar cells and catalyst — a matchmaking activity best guided by a roadmap. The approach presented by the team allows for each component of the artificial leaf to be tested individually, then combined.

The voltage produced by a standard silicon solar cell, about 0.7 volts, is insufficient to power the water-splitting reaction, which needs more than 1.2 volts. One solution is to pair multiple solar cells in series. While this leads to some losses at the interface between the cells, it is a promising direction for the research, Buonassisi says.

An additional source of inefficiency is the water itself — the pathway that the electrons must traverse to complete the electrical circuit — which has resistance to the electrons, Buonassisi says. So another way to improve efficiency would be to lower that resistance, perhaps by reducing the distance that ions must travel through the liquid.

"The solution resistance is challenging," Cox says. But, she adds, there are "some tricks" that might help to reduce that resistance, such as reducing the distance between the two sides of the reaction by using interleaved plates.

"In our simulations, we have a framework to determine the limits of efficiency" that are possible with such a system, Buonassisi says. For a system based on conventional silicon solar cells, he says, that limit is about 16 percent; for gallium arsenide cells, a widely touted alternative, the limit rises to 18 percent.

Models to determine the theoretical limits of a given system often lead researchers to pursue the development of new systems that approach those limits, Buonassisi says. "It's usually from these kinds of models that someone gets the courage to go ahead and make the improvements," he says.

"Some of the most impactful papers are ones that identify a performance limit," Buonassisi says. But, he adds, there's a "dose of humility" in looking back at some earlier projections for the limits of solar-cell efficiency: Some of those predicted "limits" have already been exceeded, he says.

"We don't always get it right," Buonassisi says, but such an analysis "lays a roadmap for development and identifies a few 'levers' that can be worked on."

INFORMATION:

The work was supported by the National Science Foundation, the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, the Singapore National Research Foundation through the Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology, and the Chesonis Family Foundation.

Written by David Chandler, MIT News Office

END

Human activities are not the primary cause of arsenic found in groundwater in Bangladesh.

Instead, a team of researchers from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Barnard College, Columbia University, University of Dhaka, Desert Research Institute and University of Tennessee found that the arsenic in groundwater in the region is part of a natural process that predates any recent human interaction, such as intensive pumping.

The results appear in the March 4 edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Millions of people in Bangladesh and neighboring ...

(Boston) – Researchers at Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM) and VA Boston Healthcare System (VA BHS) have found that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can help relieve pain for people with painful diabetic neuropathies. The study, which is the first of its kind to examine this treatment for people with type II diabetes mellitus, is published in the March issue of the Journal of Pain.

Type II diabetes mellitus is the most common form of the disease and affects more than 20 million Americans. The onset of type II diabetes mellitus is often gradual, occurring ...

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Since the mid-1800s, doctors have used drugs to induce general anesthesia in patients undergoing surgery. Despite their widespread use, little is known about how these drugs create such a profound loss of consciousness.

In a new study that tracked brain activity in human volunteers over a two-hour period as they lost and regained consciousness, researchers from MIT and Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) have identified distinctive brain patterns associated with different stages of general anesthesia. The findings shed light on how one commonly used ...

VIDEO:

NASA scientists at the Goddard Cosmic Ice Lab are studying a kind of chemistry almost never found on Earth. The extreme cold, hard vacuum, and high radiation environment of space...

Click here for more information.

Behind locked doors, in a lab built like a bomb shelter, Perry Gerakines makes something ordinary yet truly alien: ice. This isn't the ice of snowflakes or ice cubes. No, this ice needs such intense cold and low pressure to form that the right conditions ...

Back in 2010, the ideas behind a squid's sticky tendrils and Spiderman's super-strong webbing were combined to create a prototype for the first remote device able to stop vehicles in their tracks: the Safe, Quick, Undercarriage Immobilization Device (SQUID). At the push of a button, spiked arms shot out and entangled in a car's axles—bringing a racing vehicle to a screeching halt.*

The need to stop vehicles remotely was identified by the law enforcement community. With funding from Homeland Security's Science & Technology Directorate, and the expertise of the engineers ...

SEATTLE—Researchers used electronic health records to identify Group Health patients who weren't screened regularly for cancer of the colon and rectum—and to encourage them to be screened. This centralized, automated approach doubled these patients' rates of on-time screening—and saved health costs—over two years. The March 5 Annals of Internal Medicine published the randomized controlled trial.

"Screening for colorectal cancer can save lives, by finding cancer early—and even by detecting polyps before cancer starts," said study leader Beverly B. Green, MD, MPH. "But ...

Studied for decades for their essential role in making proteins within cells, several amino acids known as tRNA synthetases were recently found to have an unexpected – and critical – additional role in cancer metastasis in a study conducted collaboratively in the labs of Karen Lounsbury, Ph.D., University of Vermont professor of pharmacology, and Christopher Francklyn, Ph.D., UVM professor of biochemistry. The group determined that threonyl tRNA synthetase (TARS) leads a "double life," functioning as a critical factor regulating a pathway used by invasive cancers to induce ...

VANCOUVER, Wash.—Fishers near marine protected areas end up traveling farther to catch fish but maintain their social and economic well-being, according to a study by fisheries scientists at Washington State University and in Hawaii.

The study, reported in the journal Biological Conservation, is one of the first to look closely at how protected areas in small nearshore fisheries can affect where fishers operate on the ocean and, as a consequence, their livelihood.

"Where MPAs are located in relation to how fishers operate on the seascape is critical to understand for ...

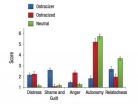

If you think giving someone the cold shoulder inflicts pain only on them, beware. A new study shows that individuals who deliberately shun another person are equally distressed by the experience.

"In real life and in academic studies, we tend to focus on the harm done to victims in cases of social aggression," says co-author Richard Ryan, professor of clinical and social psychology at the University of Rochester. "This study shows that when people bend to pressure to exclude others, they also pay a steep personal cost. Their distress is different from the person excluded, ...

Domestic violence in New Jersey

Article provided by Keith, Winters & Wenning, L.L.C.

Visit us at http://www.kwwlawfirm.com

Everyone thought the story was over. In 2009 pop sensation Rihanna was brutally assaulted by her then boyfriend Chris Brown. The singer stated that she ended the relationship and the media applauded her brave move. She became a role model for domestic violence victims around the world.

That is, until January of 2013 when the star publicly announced that she had rekindled her relationship with her convicted abuser. Unfortunately, Rihanna's ...