(Press-News.org) Researchers have for the first time demonstrated that mechanical forces can control the depolymerization of actin, a critical protein that provides the major force-bearing structure in the cytoskeletons of cells. The research suggests that forces applied both externally and internally may play a much larger role than previously believed in regulating a range of processes inside cells.

Using atomic force microscopy (AFM) force-clamp experiments, the research found that tensile force regulates the kinetics of actin dissociation by prolonging the lifetimes of bonds at low force range, and by shortening bond lifetimes beyond a force threshold. The research also identified a possible molecular basis for the bonds that form when mechanical forces create new interactions between subunits of actin.

Found in the cytoskeleton of nearly all cells, actin forms dynamic microfilaments that provide structure and sustain forces. A cell's ability to assemble and disassemble actin allows it to rapidly move or change shape in response to the environment.

The research was reported March 4 in the early online edition of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

"For the first time, we have shown that mechanical force can directly regulate how actin is assembled and disassembled," said Larry McIntire, chair of the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory University and corresponding author of the study. "Actin is fundamental to how cells accomplish most of their functions and processes. This research gives us a whole new way of thinking about how a cell can do things like rearrange its cytoskeleton in response to external forces."

The external forces affecting a cell could arise from such mechanical actions as blood flow, trauma to the body, or the loading of bones and other tissue as organisms move around.

"Forces are applied to cells all the time, and often they are directional, not uniformly applied in a certain direction," said McIntire. "The cell can rearrange its cytoskeleton to either accommodate the forces that are being applied, or apply its own forces to do something – such as moving to go after food."

Because these forces regulate the polymerization and depolymerization of actin, they load the actin fibers in a specific direction, affecting the duration of bonds that may influence cellular growth in one direction, he said.

For instance, tensile forces applied to the actin produce catch bonds, in which the bond lifetime increases as the force increases. These catch bonds have been shown to exist in other proteins, but actin is the most important protein known to form the structures. Most bonds at the cellular level are slip bonds which, unlike catch bonds, dissociate more quickly with application of force.

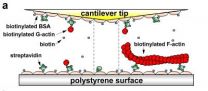

The researchers used a specially-constructed AFM to conduct their experiments. The tip was coated with actin monomers, while a polystyrene surface below the AFM tip was coated with either monomeric or filamentous actin. To study the catch-slip bonds, the tip was driven close to the surface to allow bond formation, then retracted to pull on the bond. The tension was held stationary to measure the bond lifetime at a constant force.

The research team also used molecular dynamics simulations to predict the specific amino acids likely to be important in forming the catch bonds. Experiments using specialized reagents confirmed the molecular mechanism, a lysine-glutamic acid-salt bridge believed to be responsible for forming long-lived bonds between actin sub-units when force is applied to them.

"What we found was that when you apply force, the force induces additional interactions at the atomic scale," said Cheng Zhu, a Regents' professor in the Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering and co-corresponding author of the paper. "When you apply force, you find that residues that had previously not been making contact are now interacting. These are force-induced interactions."

Proof that force application can play a role in the internal functions of cells demonstrates the growing importance of a relatively new field of research known as mechano-biology, which studies how mechanical activities affect living tissues.

"We know that the cell can sense the mechanical environment around it," said Zhu. "One of the cell's responses to the mechanical environment is to change shape and reorganize the actin cytoskeleton. Previously, it was thought that sensory molecules at the cell surface were required to convert the mechanical cues into biochemical signals before the actin cytoskeleton could be altered. The mechanism we describe can bypass the cellular signaling mechanisms because actin bears the force in the cell."

The work sets the stage for additional research into other biochemical reactions that may be produced by the application of force.

"It's becoming more and more clear that the ability of the cell to vary its mechanical environment, in addition to responding to what's going on outside it, is crucial to a lot of what goes on with the biochemistry in the cell functions," McIntire added. "If you can change the structure of the amino acids by pulling on them, and that force is applied to an enzymatic site, you can increase or decrease the enzymatic activity by changing the local structure of the amino acids."

INFORMATION:

The research was inspired by a 2005 paper from the Shu Chien lab at the University of California at San Diego, and was carried out by Georgia Tech graduate student Cho-yin Lee (now at the National Taiwan University Hospital) and research scientist Jizhong Lou (now at the Chinese Academy of Sciences), with intellectual input from Suzanne B. Eskin from Georgia Tech and Shoichiro Ono from Emory University. Kuo-kuang Wen and Melissa McKane from the laboratory of Peter A. Rubenstein at the University of Iowa provided actin mutants used in the research.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under grants HL18672, HL70537, HL091020, HL093723, AI077343, AI044902, AR48615 and DC8803, and by the National Natural Science Foundation of China grants 31070827, 31222022 and 81161120424. The conclusions are those of the principal investigators and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Mechanical forces play key role in assembly and disassembly of an essential cell protein

Regulating cells

2013-03-20

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

SMU Lyle School of Engineering course sparks CCL study

2013-03-20

DALLAS (SMU) – The Innovation Gym in SMU's Lyle School of Engineering was buzzing and clanking on a recent morning as students tested robots they built for a specific task – collecting and remediating water samples, as Lyle faculty and students have been doing by hand in refugee camps in Africa and Bangladesh.

The strong work dynamic that emerged among members of the first-year design class and their embrace of the inter-disciplinary team approach used to teach it has drawn the attention of the Center For Creative Leadership, which will send a team of researchers to ...

Altered brain activity responsible for cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia

2013-03-20

Cognitive problems with memory and behavior experienced by individuals with schizophrenia are linked with changes in brain activity; however, it is difficult to test whether these changes are the underlying cause or consequence of these symptoms. By altering the brain activity in mice to mimic the decrease in activity seen in patients with schizophrenia, researchers reporting in the Cell Press journal Neuron on March 20 reveal that these changes in regional brain activity cause similar cognitive problems in otherwise normal mice. This direct demonstration of the link between ...

Some Alaskan trout use flexible guts for the ultimate binge diet

2013-03-20

Imagine having a daylong Thanksgiving feast every day for a month, then, only pauper's rations the rest of the year.

University of Washington researchers have discovered Dolly Varden, a kind of trout, eating just that way in Alaska's Chignik Lake watershed.

Organs such as the stomach and intestines in the Dolly Varden doubled to quadrupled in size when eggs from spawning sockeye salmon became available each August, the researchers found. They were like vacuums sucking up the eggs and nipping at the flesh of spawned-out salmon carcasses.

Then, once the pulse of eggs ...

Spiral beauty graced by fading supernova

2013-03-20

Supernovae are amongst the most violent events in nature. They mark the dazzling deaths of stars and can outshine the combined light of the billions of stars in their host galaxies.

In 1999 the Lick Observatory in California reported the discovery of a new supernova in the spiral galaxy NGC 1637. It was spotted using a telescope that had been specially built to search for these rare, but important cosmic objects [1]. Follow-up observations were requested so that the discovery could be confirmed and studied further. This supernova was widely observed and was given the ...

Estrogen helps keep joint pain at bay after hysterectomy

2013-03-20

CLEVELAND, Ohio (March 20, 2013)—Estrogen therapy can help keep joint pain at bay after menopause for women who have had a hysterectomy. Joint pain was modestly, but significantly, lower in women who took estrogen alone than in women who took placebo in the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) trial. The findings were published online today in Menopause, the journal of The North American Menopause Society.

Studies looking at how estrogen affects joint pain in women after menopause have had mixed results. But this analysis of data on some 1,000 women who had hysterectomies—representative ...

Estrogen may relieve post-menopausal joint pain

2013-03-20

Post-menopausal women, who often suffer from joint pain, could find some long-term relief by taking estrogen-only medication, according to a new study based on the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) that was released online today by the journal, Menopause.

Previous studies of estrogen's influence on joint symptoms had produced mixed results, so researchers examined the findings of the WHI, the largest-ever study of the use of hormonal therapy in post-menopausal women. They examined the findings of the women enrolled in the Estrogen-Alone program, in which women who had undergone ...

Discovery of first motor with revolution motion in a virus-killing bacteria advances nanotechnology

2013-03-20

Scientists have cracked a 35-year-old mystery about the workings of the natural motors that are serving as models for development of a futuristic genre of synthetic nanomotors that pump therapeutic DNA, RNA or drugs into individual diseased cells. Their report revealing the innermost mechanisms of these nanomotors in a bacteria-killing virus — and a new way to move DNA through cells — is being published online today in the journal ACS Nano.

Peixuan Guo and colleagues explain that two motors have been found in nature: A linear motor and a rotating motor. Now they report ...

A milestone for new carbon-dioxide capture/clean coal technology

2013-03-20

An innovative new process that releases the energy in coal without burning — while capturing carbon dioxide, the major greenhouse gas — has passed a milestone on the route to possible commercial use, scientists are reporting. Their study in the ACS journal Energy & Fuels describes results of a successful 200-hour test on a sub-pilot scale version of the technology using two inexpensive but highly polluting forms of coal.

Liang-Shih Fan and colleagues explain that carbon capture and sequestration ranks high among the approaches for reducing coal-related emissions of the ...

Explaining how extra virgin olive oil protects against Alzheimer's disease

2013-03-20

The mystery of exactly how consumption of extra virgin olive oil helps reduce the risk of Alzheimer's disease (AD) may lie in one component of olive oil that helps shuttle the abnormal AD proteins out of the brain, scientists are reporting in a new study. It appears in the journal ACS Chemical Neuroscience.

Amal Kaddoumi and colleagues note that AD affects about 30 million people worldwide, but the prevalence is lower in Mediterranean countries. Scientists once attributed it to the high concentration of healthful monounsaturated fats in olive oil — consumed in large amounts ...

Scientists discover reasons behind snakes' 'shrinking heads'

2013-03-20

An international team of scientists led by Dr Kate Sanders from the University of Adelaide, and including Dr Mike Lee from the South Australian Museum, has uncovered how some sea snakes have developed 'shrunken heads' – or smaller physical features than their related species.

Their research is published today in the journal Molecular Ecology (doi: 10.1111/mec.12291).

A large head – "all the better to eat you with" - would seem to be indispensable to sea snakes, which typically have to swallow large spiny fish. However, there are some circumstances where it wouldn't ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Physical fitness of transgender and cisgender women is comparable, current evidence suggests

Duplicate medical records linked to 5-fold heightened risk of inpatient death

Air ambulance pre-hospital care may make surviving critical injury more likely

Significant gaps persist in regional UK access to 24/7 air ambulance services

Reproduction in space, an environment hostile to human biology

Political division in the US surged from 2008 onwards, study suggests

No need for rare earths or liquid helium! Cryogenic cooling material composed solely of abundant elements

Urban light pollution alters nighttime hormones in sharks, study shows

Pregnancy, breastfeeding associated with higher levels of cognitive function for postmenopausal women

Tiny dots, big impact: Using light to scrub industrial dyes from our water

Scientists uncover how biochar microzones help protect crops from toxic cadmium

Graphene-based materials show promise for tackling new environmental contaminants

Where fires used to be frequent, old forests now face high risk of devastating blazes

Emotional support from social media found to reduce anxiety

Backward walking study offers potential new treatment to improve mobility and decrease falls in multiple sclerosis patients

Top recognition awarded to 11 stroke researchers for science, brain health contributions

New paper proposes a framework for assessing the trustworthiness of research

Porto Summit drives critical cooperation on submarine cable resilience

University of Cincinnati Cancer Center tests treatment using ‘glioblastoma-on-a-chip’ and wafer technology

IPO pay gap hiding in plain sight: Study reveals hidden cost of ‘cheap stock’

It has been clarified that a fungus living in our body can make melanoma more aggressive

Paid sick leave as disease prevention

Did we just see a black hole explode? Physicists at UMass Amherst think so—and it could explain (almost) everything

Study highlights stressed faults in potential shale gas region in South Africa

Human vaginal microbiome is shaped by competition for resources

Test strip breakthrough for accessible diagnosis

George Coukos appointed director of new Ludwig Laboratory for Cell Therapy

SCAI expert opinion explores ‘wire-free’ angiography-derived physiology for coronary assessment

‘Masculinity crisis’: Influencers on social media promote low testosterone to young men, study finds

Pensoft and ARPHA integrate Prophy to speed up reviewer discovery across 90+ scholarly journals

[Press-News.org] Mechanical forces play key role in assembly and disassembly of an essential cell proteinRegulating cells