(Press-News.org) PHILADELPHIA — Scientists have characterized how the functionality of genetically engineered T cells administered therapeutically to patients with melanoma changed over time. The data, which are published in Cancer Discovery, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research, highlight the need for new strategies to sustain antitumor T cell functionality to increase the effectiveness of this immunotherapeutic approach.

Early clinical research has indicated that cell-based immunotherapies for cancer, in particular melanoma, have potential because patients treated with antitumor T cells frequently have an initial tumor response; however, those responses are often transient.

"The cell-based immunotherapy we utilized was that of genetically engineered T cells," said James R. Heath, Ph.D., Elizabeth W. Gilloon Professor of Chemistry at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, Calif. "This approach is the most widely applicable way to generate large numbers of highly functional antitumor T cells."

Different T cell functions are associated with distinct proteins. Heath and colleagues took a closer look at how genetically engineered T cells functioned or failed after being transferred into patients. To do this, they used a recently developed, multiplexed technology that gave them a high-resolution view of which function-associated proteins individual cells expressed.

The researchers analyzed T cells isolated from blood samples taken from three patients with melanoma at several time points after treatment with genetically engineered antimelanoma T cells. Each of the patients from whom samples were taken had exhibited a different level of response to the immunotherapy.

The most highly functioning genetically engineered antimelanoma T cells made up about 10 percent of the total population of transferred T cells.

"However, they dominated the immune response," Heath said. "In other words, 10 percent of the cells are putting out 100 times more protein than the other cells."

Although these highly functioning genetically engineered T cells had high tumor-killing capabilities when a patient first received them, those capabilities disappeared within two to three weeks.

"The genetically engineered T cells did recover their high functional capacity, but those functions no longer included tumor-killing," Heath said. "However, there was another population of T cells that emerged at around one month that did exhibit tumor-killing characteristics."

These new T cells appeared to be a byproduct, through a process known as epitope spreading, of the original genetically engineered, tumor-killing T cells the patient received, Heath explained. The researchers also discovered one potential cause for the transient response to T cell therapy. Results showed that as the patient's own immune system recovered, after its initial depletion prior to therapy, those recovering T cells appeared to inhibit the antitumor immune response.

###

Follow the AACR on Twitter: @aacr

Follow the AACR on Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/aacr.org

About the American Association for Cancer Research

Founded in 1907, the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) is the world's first and largest professional organization dedicated to advancing cancer research and its mission to prevent and cure cancer. AACR membership includes more than 34,000 laboratory, translational and clinical researchers; population scientists; other health care professionals; and cancer advocates residing in more than 90 countries. The AACR marshals the full spectrum of expertise of the cancer community to accelerate progress in the prevention, biology, diagnosis and treatment of cancer by annually convening more than 20 conferences and educational workshops, the largest of which is the AACR Annual Meeting with more than 17,000 attendees. In addition, the AACR publishes eight peer-reviewed scientific journals and a magazine for cancer survivors, patients and their caregivers. The AACR funds meritorious research directly as well as in cooperation with numerous cancer organizations. As the scientific partner of Stand Up To Cancer, the AACR provides expert peer review, grants administration and scientific oversight of team science and individual grants in cancer research that have the potential for near-term patient benefit. The AACR actively communicates with legislators and policymakers about the value of cancer research and related biomedical science in saving lives from cancer. For more information about the AACR, visit http://www.AACR.org.

Functional characteristics of antitumor T cells change w increasing time after therapeutic transfer

2013-03-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Adults worldwide eat almost double daily AHA recommended amount of sodium

2013-03-21

Seventy-five percent of the world's population consumes nearly twice the daily recommended amount of sodium (salt), according to research presented at the American Heart Association's Nutrition, Physical Activity and Metabolism and Cardiovascular Disease Epidemiology and Prevention 2013 Scientific Sessions.

Global sodium intake from commercially prepared food, table salt, salt and soy sauce added during cooking averaged nearly 4,000 mg a day in 2010.

The World Health Organization recommends limiting sodium to less than 2,000 mg a day and the American Heart Association ...

Japanese researchers identify a protein linked to the exacerbation of COPD

2013-03-21

Researchers from the RIKEN Advanced Science Institute and Nippon Medical School in Japan have identified a protein likely to be involved in the exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). This protein, Siglec-14, could serve as a potential new target for the treatment of COPD exacerbation.

In a study published today in the journal Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences the researchers show that COPD patients who do not express Siglec-14, a glycan-recognition protein, are less susceptible to exacerbation compared with those who do.

COPD is a chronic ...

Scripps Research study underlines potential of new technology to diagnose disease

2013-03-21

JUPITER, FL – March 21, 2013 – Researchers at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) in Jupiter, FL, have developed cutting-edge technology that can successfully screen human blood for disease markers. This tool may hold the key to better diagnosing and understanding today's most pressing and puzzling health conditions, including autoimmune diseases.

"This study validates that the 'antigen surrogate' technology will indeed be a powerful tool for diagnostics," said Thomas Kodadek, PhD, a professor in the Departments of Chemistry and Cancer Biology and vice chairman of ...

BUSM researchers identify chemical compounds that halt virus replication

2013-03-21

(Boston) – Researchers at Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM) have identified a new chemical class of compounds that have the potential to block genetically diverse viruses from replicating. The findings, published in Chemistry & Biology, could allow for the development of broad-spectrum antiviral medications to treat a number of viruses, including the highly pathogenic Ebola and Marburg viruses.

Claire Marie Filone, PhD, postdoctoral researcher at BUSM and the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID), is the paper's first ...

ACMG releases report on incidental findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing

2013-03-21

The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) released the widely-anticipated "ACMG Recommendations for Reporting of Incidental Findings in Clinical Exome and Genome Sequencing" report at its 2013 Annual Clinical Genetics Meeting today in Phoenix. The ACMG Annual Clinical Genetics Meeting is one of the largest gatherings of medical and health professionals in genetics in the world.

As exome and genome sequencing become more commonly used in medical care, doctors will increasingly be able to learn about genetic changes that increase an individual's risk ...

Can we treat a 'new' coronary heart disease risk factor?

2013-03-21

NEW YORK – Depressive symptoms after heart disease are associated with a markedly increased risk of death or another heart attack. However, less has been known about whether treating heart attack survivors for depressive symptoms could relieve these symptoms, be cost-effective, and ultimately, reduce medical risk? Columbia University Medical Center's Karina W. Davidson, PhD and her research team now report a patient-centered approach that answers these questions in the affirmative.

With a grant from the National Institutes of Health's National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute ...

Exploring the link between traumatic brain injury and people who are homeless

2013-03-21

TORONTO, March 21, 2013—Homeless people and their health care providers need to know more about traumatic brain injuries to help prevent and treat such injuries, a new study has found.

Homeless people have a disproportionately higher risk for TBI compared to the general population, yet little is known about the severity of those injuries, who exactly is suffering from them and what the long-term consequences are.

"A better understanding of TBI, its presentation and characteristics in the homeless is vital in order to enable appropriate interventions, treatments, and ...

Dysfunction in cerebellar Calcium channel causes motor disorders and epilepsy

2013-03-21

A dysfunction of a certain Calcium channel, the so called P/Q-type channel, in neurons of the cerebellum is sufficient to cause different motor diseases as well as a special type of epilepsy. This is reported by the research team of Dr. Melanie Mark and Prof. Dr. Stefan Herlitze from the Ruhr-Universität Bochum. They investigated mice that lacked the ion channel of the P/Q-type in the modulatory input neurons of the cerebellum. "We expect that our results will contribute to the development of treatments for in particular children and young adults suffering from absence ...

Misregulated genes may have big autism role

2013-03-21

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — A new study finds that two genes individually associated with rare autism-related disorders are also jointly linked to more general forms of autism. The finding suggests a new genetic pathway to investigate in general autism research.

The genes encode the proteins NHE6 and NHE9, which are responsible for biochemical exchanges in the endosomes of cells. Mutations in the NHE6 gene are a direct cause of Christianson Syndrome, while mutations in the NHE9 gene lead to a severe form of autism with epilepsy. In the new study, a statistical ...

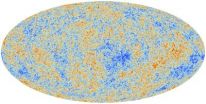

Planck's 'child' universe

2013-03-21

"We are very excited, we are finally seeing the concrete results of so many years of hard work". This is how the scientists of the Planck project have commented the first data resulting from the observations carried out by Planck. The mission of the ESA satellite is to observe the past of our Universe, going back in time and reaching the very first instant right after the Big Bang. The image that the Planck scientists convey today is that of a 'child' Universe, dating back to about 380,000 years after the Big Bang, when its temperature was similar to that of the most external ...