(Press-News.org) Beverly, MA, August 18, 2014 – Investigators from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) have successfully transplanted hearts from genetically engineered piglets into baboons' abdomens and had the hearts survive for more than one year, twice as long as previously reported. This was achieved by using genetically engineered porcine donors and a more focused immunosuppression regimen in the baboon recipients, according to a study published in The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, an official publication of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

Cardiac transplantation is the treatment of choice for end stage heart failure. According to the NHLBI, approximately 3,000 people in the US are on the waiting list for a heart transplant, while only 2,000 donor hearts become available each year. For cardiac patients currently waiting for organs, mechanical assist devices are the only options available. These devices, however, are imperfect and experience issues with power supplies, infection, and problems with blood clots and bleeding.

Transplantation using an animal organ, or xenotransplantation, has been proposed as a valid option to save human lives. "Until we learn to grow organs via tissue engineering, which is unlikely in the near future, xenotransplantation seems to be a valid approach to supplement human organ availability. Despite many setbacks over the years, recent genetic and immunologic advancements have helped revitalized progress in the xenotransplantation field," comments lead investigator Muhammad M. Mohiuddin, MD, of the Cardiothoracic Surgery Research Program at the NHLBI.

Dr. Mohiuddin's group and other investigators have developed techniques on two fronts to overcome some of the roadblocks that previously hindered successful xenotransplantation. The first advance was the ability to produce genetically engineered pigs as a source of donor organs by NHLBI's collaborator, Revivicor, Inc. The pigs had the genes that cause adverse immunologic reactions in humans "knocked out" and human genes that make the organ more compatible with human physiology were inserted. The second advance was the use of target-specific immunosuppression, which limits rejection of the transplanted organ rather than the usual generalized immunosuppression, which is more toxic.

Pigs were chosen because their anatomy is compatible with that of humans and they have a rapid breeding cycle, among other reasons. They are also widely available as a source of organs.

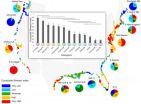

In this study, researchers compared the survival of hearts from genetically engineered piglets that were organized into different experimental groups based on the genetic modifications introduced. The gene that synthesizes the enzyme alpha 1-3 galactosidase transferase was "knocked out" in all piglets, thus eliminating one immunologic rejection target. The pig hearts also expressed one or two human transgenes to prevent blood from clotting. The transplanted hearts were attached to the circulatory systems of the host baboons, but placed in the baboons' abdomens. The baboons' own hearts, which were left in place, maintained circulatory function, and allowed the baboons to live despite the risk of organ rejection.

The researchers found that in one group (with a human gene), the average transplant survival was more than 200 days, dramatically surpassing the survival times of the other three groups (average survival 70 days, 21 days, and 80 days, respectively). Two of the five grafts in the long-surviving group stopped contracting on postoperative days 146 and 150, but the other three grafts were still contracting at more than 200 to 500 days at the time of the study's submission for publication.

Prolonged survival was attributed to several modifications. This longest-surviving group was the only one that had the human thrombomodulin gene added to the pigs' genome. Dr. Mohiuddin explains that thrombomodulin expression helps avoid some of the microvascular clotting problems that were previously associated with organ transplantation.

Another difference was the type, strength, and duration of antibody used for costimulation blockade to suppress T and B cell immune response in the hosts. In several groups, longer survival of transplants was observed with the use of anti-CD40 monoclonal antibodies but the longest-surviving group was treated specifically with a high dose of recombinant mouse-rhesus chimeric antibody (clone 2C10R4). In contrast, use of an anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody generated in a mouse (clone 3A8) did not extend survival. Anti-CD40 monoclonal antibodies also allow for faster recovery, says Dr. Mohiuddin.

No complications, including infections, were seen in the longest-survival group. The researchers used surveillance video and telemetric monitoring to identify any symptoms of complications in all groups, such as abdominal bleeding, gastrointestinal bleeding, aspiration pneumonia, seizures, or blood disorders.

The goal of the current study was to evaluate the viability of the transplants. The researchers' next step is to use hearts from the genetically-engineered pigs with the most effective immunosuppression in the current experiments to test whether the pig hearts can sustain full life support when replacing the original baboon hearts.

"Xenotransplantation could help to compensate for the shortage of human organs available for transplant. Our study has demonstrated that by using hearts from genetically engineered pigs in combination with target-specific immunosuppression of recipient baboons, organ survival can be significantly prolonged. Based on the data from long-term surviving grafts, we are hopeful that we will be able to repeat our results in the life-supporting model. This has potential for paving the way for the use of animal organs for transplantation into humans," concludes Dr. Mohiuddin.

INFORMATION:

Pigs' hearts transplanted into baboon hosts remain viable more than a year

NIH cardiac surgical scientists able to achieve prolonged survival by a combination of genetic engineering and new methods of suppressing the immune response

2014-08-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Ocean warming could drive heavy rain bands toward the poles

2014-08-18

In a world warmed by rising atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations, precipitation patterns are going to change because of two factors: one, warmer air can hold more water; and two, changing atmospheric circulation patterns will shift where rain falls. According to previous model research, mid- to high-latitude precipitation is expected to increase by as much as 50%. Yet the reasons why models predict this are hard to tease out.

Using a series of highly idealized model runs, Lu et al. found that ocean warming should cause atmospheric precipitation bands to shift toward ...

New mouse model points to therapy for liver disease

2014-08-18

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a common affliction, affecting almost 30 percent of Americans, with a significant number suffering from its most severe form, called non-alcoholic steatohepatitis or NASH, which can lead to cirrhosis and liver cancer. In recent years, NASH has become the leading cause of liver transplantation.

Development of effective new therapies for preventing or treating NASH has been stymied by limited small animal models for the disease. In a paper published online in Cancer Cell, scientists at the University of California, San Diego ...

Blood pressure medication does not cause more falls

2014-08-18

It's time to question the common belief that patients receiving intensive blood pressure treatment are prone to falling and breaking bones. A comprehensive study in people ages 40 to 79 with diabetes, led by Karen Margolis, MD, of HealthPartners Institute for Education and Research in the US, found no evidence supporting this belief. The study¹ appears in the Journal of General Internal Medicine², published by Springer.

Evidence from various clinical trials shows that cardiovascular events such as strokes can be prevented by treating high blood pressure (hypertension). ...

Study: World's primary forests on the brink

2014-08-18

August 18, 2014: An international team of conservationist scientists and practitioners has published new research showing the precarious state of the world's primary forests.

The global analysis and map are featured in a paper appearing in the esteemed journal Conservation Letters and reveals that only five percent of the world's pre-agricultural primary forest cover is now found in protected areas.

Led by Professor Brendan Mackey, Director of the Climate Change Response Program at Griffith University in Queensland, Australia, the authors are experts in forest ecology, ...

Study reveals immune system is dazed and confused during spaceflight

2014-08-18

There is nothing like a head cold to make us feel a little dazed. We get things like colds and the flu because of changes in our immune system. Researchers have a good idea what causes immune system changes on Earth—think stress, inadequate sleep and improper nutrition. But the results of two NASA collaborative investigations—Validation of Procedures for Monitoring Crewmember Immune Function (Integrated Immune) and Clinical Nutrition Assessment of ISS Astronauts, SMO-016E (Clinical Nutrition Assessment)—recently published in the Journal of Interferon & Cytokine Research ...

New tool makes online personal data more transparent

2014-08-18

New York, NY—August 18, 2014—The web can be an opaque black box: it leverages our personal information without our knowledge or control. When, for instance, a user sees an ad about depression online, she may not realize that she is seeing it because she recently sent an email about being sad. Roxana Geambasu and Augustin Chaintreau, both assistant professors of computer science at Columbia Engineering, are seeking to change that, and in doing so bring more transparency to the web. Along with their PhD student, Mathias Lecuyer, the researchers have developed XRay, a new ...

A new species of endemic treefrog from Madagascar

2014-08-18

A new species of the Boophis rappiodes group is described from the hidden streams of Ankarafa Forest, northwest of Madagascar. The study was published in the open access journal ZooKeys.

The new species Boophis ankarafensis is green in colour with bright red speckling across its head and back, but what truly distinguishes this species is a high genetic divergence and different call with a triple click, compared to the usual double.

All individuals were detected from the banks of two streams in Ankarafa Forest. The new species represents the only member of the B. ...

Project serves up big data to guide managing nation's coastal waters

2014-08-18

When it comes to understanding America's coastal fisheries, anecdotes are gripping – stories of a choking algae bloom, or a bay's struggle with commercial development. But when it comes to taking action, there's no beating big data.

In this week's edition of Estuaries and Coasts, a Michigan State University doctoral student joins with others to give a sweeping assessment to understand how human activities are affecting estuaries, the nation's sounds, bays, gulfs and bayous. These are places where freshwater flows into the oceans, and the needs of the people blend with ...

500 million year reset for the immune system

2014-08-18

This news release is available in German.

Scientists at the Max Planck Institute of Immunobiology and Epigenetics (MPI-IE) in Freiburg re-activated expression of an ancient gene, which is not normally expressed in the mammalian immune system, and found that the animals developed a fish-like thymus. To the researchers surprise, while the mammalian thymus is utilized exclusively for T cell maturation, the reset thymus produced not only T cells, but also served as a maturation site for B cells – a property normally seen only in the thymus of fish. Thus the model ...

GW researchers develop model to study impact of faculty development programs

2014-08-18

WASHINGTON (Aug. 18, 2014) — Methods used to demonstrate the impact of faculty development programs have long been lacking. A research report from the George Washington University (GW) introduces a new model to demonstrate how faculty development programming can affect institutional behaviors, beyond the individual participant.

"Faculty development is essential for helping medical education faculty meet the demands of their roles as teachers, scholars, administrators, and leaders," said co-author Ellen Goldman, MBA, Ed.D., associate professor of clinical research and ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Novel camel antimicrobial peptides show promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

Adolescent cannabis use and risk of psychotic, bipolar, depressive, and anxiety disorders

[Press-News.org] Pigs' hearts transplanted into baboon hosts remain viable more than a yearNIH cardiac surgical scientists able to achieve prolonged survival by a combination of genetic engineering and new methods of suppressing the immune response