INFORMATION:

Contact:

Eugene Polzik, professor, head of Quantop, Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen,

+45 3532-5424, polzik@nbi.dk

Georgios Vasilakis, postdoc, Quantop, Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen,

+45 3532-3000, lab.: +45 3532-5386, gvasilak@nbi.dk

Super sensitive measurement of magnetic fields

2015-03-30

(Press-News.org) There are electrical signals in the nervous system, the brain and throughout the human body and there are tiny magnetic fields associated with these signals that could be important for medical science. Researchers from the Niels Bohr Institute have just developed a method that could be used to obtain extremely precise measurements of ultra-small magnetic fields. The results are published in the scientific journal Nature Physics.

The tiny magnetic fields are all the way down on the atomic level. The atoms do not stand still, they revolve around themselves and the axis is like a tiny magnetic rod. But the axis has a slight tilt and as a result the magnetic rod swings in circles. To measure a swinging object you need to have both its position and the speed of the oscillation.

But in the world of atoms, the laws of classical physics from the world as we know it do not apply - here the laws of quantum physics rule. Heisenberg and Bohr's laws of quantum uncertainty relations state that when one measures a system, you cannot simultaneously measure the position of a particle and its speed and get a precise number. You can measure one of these variables, for example, the position and get a number with almost unlimited precision. In the same measurement, the speed of the particle would then be uncertain. If you measure the precise speed of the particle, you would then get an uncertain position in the same measurement. Likewise, the laws of quantum physics state then when you measure a rotating motion, you cannot simultaneously measure the rotational speed and direction of the rotational axis.

Precise squeezed measurements

"To get accurate measurements of ultra-small magnetic fields, we have devised a way to almost escape the limitations of quantum physics and we have conducted experiments in the laboratory where we improve the measurements of the oscillating atoms. The newly developed sensor that can measure the ultra-small magnetic field is comprised of a collection of atoms in gaseous form," explains professor Eugene Polzik, head of the research group Quantop at the Niels Bohr Institute at the University of Copenhagen.

In the quantum optics laboratory, the researchers have a small glass tube that contains a cloud of billions of caesium gas atoms. The glass tube is 10 millimeters long and has a diameter of only 300 micrometers (a micrometer is one millionth of a meter). The atoms revolve around themselves on a tilted axis, but the gas atoms are flying around helter skelter and the tilted axes of the atoms are oriented in all possible directions. Using laser light, the tilts of all the atoms are turned in the same direction. This direction could be knocked off course when the atoms crash into the glass wall, but the glass tube has an inner coating that ensures they hold course.

Now the researchers send a new beam of laser light with a different frequency into the gas atoms and then a strange quantum phenomenon takes place, the light and the gas atoms become entangled. The fact that they are entangled means that they have established a quantum link - they are synchronised and are now totally aligned. The laser light is sent with a certain pulse and you can now measure the direction of the atomic axis, but only one direction. This means that when the atoms revolve around themselves, its tilted axis forms a circle and you cannot measure the precise position of the entire circular swing of the axis. But you can divide a circle into a north/south direction and an east/west direction.

"What we then do is measure one of the directions, for example, the east/west direction. This is called a squeezed state and this can be measured with very little inaccuracy. This is very useful, because for many measurements of external magnetic fields it is only necessary to measure the east/west direction and thus we can calculate the ultra-small magnetic fields with high precision," says Eugene Polzik.

Super sensitive measurements of tiny electromagnetic fields and forces are important in relation to research in biology and medicine and the research group therefore has a collaboration with the doctors at the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences at the University of Copenhagen.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Glimpses of the future: Drought damage leads to widespread forest death

2015-03-30

Washington, D.C.-- The 2000-2003 drought in the American southwest triggered a widespread die-off of forests around the region. A Carnegie-led team of scientists developed a new modeling tool to explain how and where trembling aspen forests died as a result of this drought. It is based on damage to the individual trees' ability to transport water under water-stressed conditions.

If the same processes and threshold govern the future, their results suggest that more widespread die-offs of aspen forests triggered by climate change are likely by the 2050s. Tree mortality ...

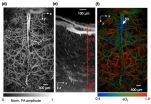

High-tech method allows rapid imaging of functions in living brain

2015-03-30

Researchers studying cancer and other invasive diseases rely on high-resolution imaging to see tumors and other activity deep within the body's tissues. Using a new high-speed, high-resolution imaging method, Lihong Wang, PhD, and his team at Washington University in St. Louis were able to see blood flow, blood oxygenation, oxygen metabolism and other functions inside a living mouse brain at faster rates than ever before.

Using photoacoustic microscopy (PAM), a single-wavelength, pulse-width-based technique developed in his lab, Wang, the Gene K. Beare Professor of Biomedical ...

Early stage NSCLC patients with low tumor metabolic activity have longer survival

2015-03-30

DENVER - Low pre-surgery uptake of a labeled glucose analogue, a marker of metabolic activity, in the primary tumor of patients with stage I non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is associated with increased overall survival and a longer time before tumor recurrence. Patients with high labeled glucose uptake may benefit from additional therapy following surgery.

Surgery is the standard of care for patients with stage I NSCLC but not all patients are cured, as demonstrated by a 5-year survival rate of less than 60% in these patients. There is a clear need for a diagnostic ...

'Pay-for-performance' may lead to higher risk for robotic prostate surgery patients

2015-03-30

DETROIT - A "perverse disincentive" for hospitals that have invested in expensive technology for robotic surgery may be jeopardizing prostate cancer patients who seek out the procedure, concluded a new study led by Henry Ford Hospital researchers.

The study, which compared complication rates in hospitals with low volumes of robot-assisted radical prostatectomies (RARPs) to institutions with high volumes of the procedure, suggested that current pay-for-performance healthcare models are to blame.

The new study was published online this month by BJU International.

"Patients ...

Fat grafting technique improves results of breast augmentation

2015-03-30

March 30, 2015 - In women undergoing breast augmentation, a technique using transplantation of a small amount of the patient's own fat cells can produce better cosmetic outcomes, reports a study in the April issue of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery®, the official medical journal of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS).

In particular, the fat grafting technique can achieve a more natural-appearing cleavage--avoiding the "separated breasts" appearance that can occur after breast augmentation, according to the report by Dr. Francisco G. Bravo of Clinica ...

Compound from soil microbe inhibits biofilm formation

2015-03-30

Researchers have shown that a known antibiotic and antifungal compound produced by a soil microbe can inhibit another species of microbe from forming biofilms--microbial mats that frequently are medically harmful--without killing that microbe. The findings may apply to other microbial species, and can herald a plethora of scientific and societal benefits. The research is published online ahead of print on March 30, 2015, in the Journal of Bacteriology, a publication of the American Society for Microbiology. The study will be printed in a special section of the journal ...

Roll up your screen and stow it away?

2015-03-30

From smartphones and tablets to computer monitors and interactive TV screens, electronic displays are everywhere. As the demand for instant, constant communication grows, so too does the urgency for more convenient portable devices -- especially devices, like computer displays, that can be easily rolled up and put away, rather than requiring a flat surface for storage and transportation.

A new Tel Aviv University study, published recently in Nature Nanotechnology, suggests that a novel DNA-peptide structure can be used to produce thin, transparent, and flexible screens. ...

Princess Margaret scientists convert microbubbles to nanoparticles

2015-03-30

(TORONTO, Canada - March 30, 2015) - Biomedical researchers led by Dr. Gang Zheng at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre have successfully converted microbubble technology already used in diagnostic imaging into nanoparticles that stay trapped in tumours to potentially deliver targeted, therapeutic payloads.

The discovery, published online today in Nature Nanotechnology, details how Dr. Zheng and his research team created a new type of microbubble using a compound called porphyrin - a naturally occurring pigment in nature that harvests light.

In the lab in pre-clinical ...

Mother's diet influences weight-control neurocircuits in offspring

2015-03-30

Maternal diet during pregnancy and lactation may prime offspring for weight gain and obesity later in life, according to Penn State College of Medicine researchers, who looked at rats whose mothers consumed a high-fat diet and found that the offsprings' feeding controls and feelings of fullness did not function normally.

Previous research shows that obesity compromises the neurocircuits that control how the stomach and intestine work to regulate how much we eat, and that the time around pregnancy and lactation is important in the development of these circuits. In both ...

Study: Worked-based wellness programs reduce weight

2015-03-30

A new study shows that workplace wellness programs can be effective in helping people lose weight by providing healthier food choices and increasing opportunities for physical activity, particularly if these efforts are designed with the input and active participation of employees. The two-year project - the results of which appear in the American Journal of Public Health - successfully reduced the number or people considered overweight or obese by almost 9 percent.

"Worksites are self-contained environments with established communication systems where interventions ...