(Press-News.org) DURHAM, N.C. -- We've all seen dewdrops form on spider webs. But what if they flung themselves off of the strands instead?

Researchers at Duke University and the University of British Columbia have now observed this peculiar phenomenon, which could benefit many industrial applications. As long as the strands are moderately hydrophobic and relatively thin, small droplets combining into one are apt to dance themselves right off of the tightrope. The discovery could form the basis of new coalescer technologies for water purification, oil refining and more.

The findings were reported online on August 14, 2015, in Physical Review Letters.

"We were studying how insect wings with a hairy structure clean themselves, and an undergrad Adam Williams saw two droplets merge and suddenly leave a strand of hair," said Chuan-Hua Chen, associate professor of mechanical engineering and materials science at Duke. "Since we couldn't easily reproduce the effect, we thought it was just an artifact, perhaps due to the slight breeze created by the humidifier in the experiment."

But thanks to some ingenuity from Kungang Zhang, a graduate student in Chen's group, they discovered that the "dancing droplets" are real, and are more likely to propel themselves off of a strand if they merge from opposite sides -- a finding that allowed the team to study the phenomenon in detail.

As a droplet grows larger, it stores energy on its expanding surface. When two droplets merge, the mass stays the same, but the surface area decreases. This causes a small amount of energy to be released. As long as the drops are only attached to a small solid area, the released energy is enough to fling them away. This proves true so long as the strand is reasonably hydrophobic, such as the Teflon-coated fibers in the experiment, and the diameter of the strand is a few times smaller than that of the droplet.

In previous research, Chen and his team showed a similar self-cleaning method from the wings of cicadas where droplets could launch themselves from a flat surface. That surface, however, was super-hydrophobic due to the nanostructure of the wings.

"In engineering systems, these nanostructures are concerns for reliability," said Chen. "Our new finding provides a solution without resorting to these super-hydrophobic surfaces."

A potential application of the dancing phenomenon is in water purification technologies. Current methods use gravity or shearing forces to remove accumulated droplets from fibrous webs, much like those found on your morning walk through the woods. If the droplets get too large, however, they can clog the gaps in the web. But with this new finding, fibrous woven materials could be engineered with Teflon-like coatings and large enough gaps to never clog before droplets jump off.

"Before we demonstrated this, people thought you'd never be able to get the self-propelled phenomenon on a moderately hydrophobic surface," said Chen. "But now we've shown that you don't need super-hydrophobicity to get this dancing effect. All you need are round fibers instead of flat surfaces."

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation.

"Self-Propelled Droplet Removal from Hydrophobic Fiber-Based Coalescers." Kungang Zhang, Fangjie Liu, Adam J. Williams, Xiaopeng Qu, James J. Feng, and Chuan-Hua Chen. Physical Review Letters, 2015. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.115.074502

Seasonal water shortages already occur in the Central Andes of Peru and Bolivia. By the end of the century, precipitation could fall by up to 30% according to an international team of researchers led by the University of Zurich. In a first for this region, the team compared current climate data with future climate scenarios and data extending back to pre-Inca times.

The population in the Central Andes already faces water shortages today. Now geographers at the University of Zurich have collaborated with Swiss and South American researchers to show that precipitation in ...

Over a 10 year period, the time that babies receive genetic testing after being diagnosed with diabetes has fallen from over four years to under two months. Pinpointing the exact genetic causes of sometimes rare forms of diabetes is revolutionising healthcare for these patients.

Babies with diabetes are now being immediately genetically tested for all possible 22 genetic causes while previously they would only get genetic testing years after diabetes was diagnosed and then the genes would be tested one at a time. Crucially, this means that the genetic diagnosis is made ...

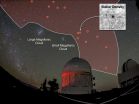

Scientists on the Dark Energy Survey, using one of the world's most powerful digital cameras, have discovered eight more faint celestial objects hovering near our Milky Way galaxy. Signs indicate that they, like the objects found by the same team earlier this year, are likely dwarf satellite galaxies, the smallest and closest known form of galaxies.

Satellite galaxies are small celestial objects that orbit larger galaxies, such as our own Milky Way. Dwarf galaxies can be found with fewer than 1,000 stars, in contrast to the Milky Way, an average-size galaxy containing ...

We may view our memory as being essential to who we are, but new findings suggest that others consider our moral traits to be the core component of our identity. Data collected from family members of patients suffering from neurodegenerative disease showed that it was changes in moral behavior, not memory loss, that caused loved ones to say that the patient wasn't "the same person" anymore.

The findings are published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

"Contrary to what you might think -- and what generations of philosophers ...

WASHINGTON, August 17, 2015 -- Almost all of us have used some type of odor eliminator like Febreze to un-stink a room. These sprays can work wonders, but how do they actually work? Do they really remove the smell or just mask it? We explain the chemistry of odor elimination in this week's Reactions video. Check it out here: https://youtu.be/sNIIxzR-d_Q.

Subscribe to the series at http://bit.ly/ACSReactions, and follow us on Twitter @ACSreactions to be the first to see our latest videos.

INFORMATION:

The American Chemical Society is a nonprofit organization chartered ...

This news release is available in German.

Their results have now been published in the Nature journal Scientific Reports (doi:10.1038/srep13008) and could point the way toward improvements in hybrid solar cells.

The system they investigated is based on conventional n-type silicon wafers coated with the highly conductive polymer mixture PEDOT:PSS and displays a power conversion efficiency of about 14 %. This combination of materials is currently extensively investigated by many teams in the research community.

"We systematically surveyed the characteristic curves, ...

Millions of tons of road salt are applied to streets and highways across the United States each winter to melt ice and snow and make travel safer, but the effects of salt on wildlife are poorly understood.

A new study by biologists from Case Western Reserve University suggests exposure to road salt, as it runs off into ponds and wetlands where it can concentrate--especially during March and early April, when frogs are breeding--may increase the size of wood frogs, but also shorten their lives.

Wood frog tadpoles exposed to road salt grew larger and turned into ...

In addition to melting icecaps and imperiled wildlife, a significant concern among scientists is that higher Arctic temperatures brought about by climate change could result in the release of massive amounts of carbon locked in the region's frozen soil in the form of carbon dioxide and methane. Arctic permafrost is estimated to contain about a trillion tons of carbon, which would potentially accelerate global warming. Carbon emissions in the form of methane have been of particular concern because on a 100-year scale methane is about 25-times more potent than carbon dioxide ...

Magnetism in nanoscale layers only a few tens of atoms thick is one of the foundations of the big data revolution - for example, all the information we download from the internet is stored magnetically on hard disks in server farms dotted across the World. Recent work by a team of scientists working in Singapore, The Netherlands, USA and Ireland, published on 14 August 2015 in the prestigious journal, Science, has uncovered a new twist to the story of thin-film magnetism.

The team from the National University of Singapore (NUS) - Mr Li Changjian, a graduate student from ...

Bilingual children pose unique challenges for clinicians, and, until recently, there was little research on young bilinguals to guide clinical practice. In the past decade, however, research on bilingual development has burgeoned, and the scientific literature now supports several conclusions that should help clinicians as they assess bilingual children and advise their parents.

In an article recently published in Seminars in Speech and Language, Erika Hoff, Ph.D., a professor of psychology in the Charles E. Schmidt College of Science at Florida Atlantic University, ...