(Press-News.org) The structure of a man's face may indicate his tendency to express racially prejudiced beliefs, according to new research published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

Studies have shown that facial width-to-height ratio (fWHR) is associated with testosterone-related behaviors, which some researchers have linked with aggression. But psychological scientist Eric Hehman of Dartmouth College and colleagues at the University of Delaware speculated that these behaviors may have more to do with social dominance than outright aggression.

The researchers decided to examine the relationship between fWHR and dominance in the specific context of racial prejudice.

"Racial prejudice is such a sensitive issue and there are societal pressures to appear nonprejudiced. More dominant individuals might care less about appearing prejudiced, or exercise less self-regulation with regard to reporting those prejudices, should they exist," says Hehman, who conducted the research as a graduate student at the University of Delaware.

The researchers asked male participants about their willingness to express racially prejudiced beliefs and about the pressure they feel to adhere to societal norms. The results revealed that men who have higher fWHR (determined from photos of their faces) are more likely to express racist remarks and are less concerned about how others perceive those remarks.

Importantly, these results did not show that the men were necessarily more prejudiced — men with greater fWHR did not score higher on measures that assessed implicit, or more automatic, racial prejudice. Rather, these men were simply more likely to express any prejudicial beliefs they may have had.

"Not all people with greater fWHRs are prejudiced, and not all those with smaller fWHRs are non-prejudiced," says Hehman. "You could think about it as a 'side effect' of social dominance — men with greater fWHR may not care as much about what others think of them."

Results from a second study suggest that observers actually perceive and use fWHR when evaluating another person's degree of prejudice.

Looking at the photos from the first study, a new group of participants evaluated men with wider, shorter faces as more prejudiced, and they were able to accurately estimate the target's self-reported prejudicial beliefs just by looking at an image of his face. The results were confirmed in a third study.

The third study also showed that non-White participants, whose outcomes are more likely to be influenced by their race or ethnicity, were more motivated to accurately assess targets' prejudice. This greater motivation, in turn, was associated with increased accuracy. The finding is consistent with the idea that people allocate their attention to stimuli that can influence their outcomes.

Together, these three studies add to a growing literature exploring how people perceive and accurately infer personality characteristics based on physical appearance.

"This research provides the first evidence for a facial metric that not only predicts important and controversial social behaviors, such as reporting prejudices, but can also be used by others to make accurate judgments," says Hehman.

These studies may open up new avenues of research; Hehman and colleagues speculate that fWHR may be linked with explicit prejudice on a number of different dimensions beyond race.

###

In addition to Hehman, authors on the study include Jordan B. Leitner, Matthew P. Deegan, and Samuel L. Gaertner, all of the University of Delaware.

For more information about this study, please contact: Eric Hehman at eric.hehman@dartmouth.edu.

The APS journal Psychological Science is the highest ranked empirical journal in psychology. For a copy of the article "Facial Structure Is Indicative of Explicit Support for Prejudicial Beliefs" and access to other Psychological Science research findings, please contact Anna Mikulak at 202-293-9300 or amikulak@psychologicalscience.org.

Facial structure may predict endorsement of racial prejudice

2013-02-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

NASA scientists part of Arctic Sea ice study

2013-02-14

New research using combined records of ice measurements from NASA's Ice, Cloud and Land Elevation Satellite (ICESat), the European Space Agency's CryoSat-2 satellite, airborne surveys and ocean-based sensors shows Arctic sea ice volume declined 36 percent in the autumn and 9 percent in the winter over the last decade. The work builds on previous studies using submarine and NASA satellite data and confirms computer model estimates that showed ice volume decreases over the last decade, and builds a foundation for a multi-decadal record of sea ice volume changes.

In a report ...

Resignation of Pope Benedict XVI demands a close look at rules of modern papal election

2013-02-14

New Rochelle, NY, February 13, 2013—When Pope Benedict XVI ends his reign at the end of February he will be the first pope to do so before his death in nearly 600 years. He shocked the Catholic Church by announcing his resignation and set in place a centuries-old process to select his successor. The fascinating Conclaves system for electing a new pope, which has been in place since the late 1200s is described in "Creating the Rules of the Modern Papal Election," published in Election Law Journal, from Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., publishers. The article is available on the Election ...

Why there are bad learners: EEG activity predicts learning success

2013-02-14

The reason why some people are worse at learning than others has been revealed by a research team from Berlin, Bochum, and Leipzig, operating within the framework of the Germany-wide network "Bernstein Focus State Dependencies of Learning". They have discovered that the main problem is not that learning processes are inefficient per se, but that the brain insufficiently processes the information to be learned. The scientists trained the subjects' sense of touch to be more sensitive. In subjects who responded well to the training, the EEG revealed characteristic changes ...

Genetic study pursues elusive goal: How many humpbacks existed before whaling?

2013-02-14

Scientists from Stanford University, the Wildlife Conservation Society, the American Museum of Natural History, and other organizations are closing in on the answer to an important conservation question: how many humpback whales once existed in the North Atlantic?

Building on previous genetic analyses to estimate the pre-whaling population of North Atlantic humpback whales, the research team has found that humpbacks used to exist in numbers of more than 100,000 individuals. The new, more accurate estimate is lower than previously calculated but still two to three times ...

Robots with lift

2013-02-14

They can already stand, walk, wriggle under obstacles, and change colors. Now researchers are adding a new skill to the soft robot arsenal: jumping.

Using small explosions produced by a mix of methane and oxygen, researchers at Harvard have designed a soft robot that can leap as much as a foot in the air. That ability to jump could one day prove critical in allowing the robots to avoid obstacles during search and rescue operations. The research is described in a Feb. 6 paper in the international edition of Angewandte Chemie.

"Initially, our soft robot systems used pneumatic ...

Study supports regulation of hospitals

2013-02-14

EAST LANSING, Mich. — Hospital beds tend to get used simply because they're available – not necessarily because they're needed, according to a first-of-its-kind study that supports continued regulation of new hospitals.

Michigan State University researchers examined all 1.1 million admissions at Michigan's 169 acute-care hospitals in 2010 and found a strong correlation between bed availability and use, even when accounting for myriad factors that may lead to hospitalization. These factors include nature of the ailment, health insurance coverage, access to primary care ...

Clues to chromosome crossovers

2013-02-14

Neil Hunter's laboratory in the UC Davis College of Biological Sciences has placed another piece in the puzzle of how sexual reproduction shuffles genes while making sure sperm and eggs get the right number of chromosomes.

The basis of sexual reproduction is that a fertilized egg gets half its chromosomes from each parent — sperm and eggs each contributing one partner in each pair of chromosomes. We humans have 23 pairs of 46 chromosomes: so our sperm or eggs have 23 chromosomes each.

Before we get to the sex part, though, those sperm and eggs have to be formed from ...

Preventing obesity transmission during pregnancy

2013-02-14

A much neglected part of the obesity epidemic is that it has resulted in more overweight/obese women before and during pregnancy. Their offspring also tend to have higher birth weights and more body fat, and carry an increased risk of obesity and chronic diseases later in life. However, the nutritional factors and mechanisms involved pre and during pregnancy that may influence child obesity remain uncertain. A recent publication by ILSI Europe identifies and discusses key contributing factors leading to obesity.

In an article recently published in Annals of Nutrition and ...

Probiotic-derived treatment offers new hope for premature babies

2013-02-14

BETHESDA, Md. (Feb. 13, 2013)—"Good" bacteria that live in our intestines have been linked with a variety of health benefits, from fighting disease to preventing obesity. In a new study, Kriston Ganguli of Massachusetts General Hospital for Children and Harvard Medical School and her colleagues have discovered another advantage to these friendly microscopic tenants: Chemicals secreted by good bacteria that typically live in the intestines of babies could reduce the frequency and severity of a common and often-lethal disease of premature infants.

This disease, known as ...

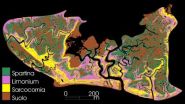

Marsh plants actively engineer their landscape

2013-02-14

DURHAM, NC -- Marsh plants, far from being passive wallflowers, are "secret gardeners" that actively engineer their landscape to increase their species' odds of survival, says a team of scientists from Duke University and the University of Padova in Italy.

Scientists have long believed that the distribution of plants within a marsh is a passive adaption in which species grow at different elevations because that's where conditions like soil aeration and salinity best meet their needs.

But this team found intertidal marsh plants in Italy's famed Venetian lagoon were ...