(Press-News.org) Scientists from Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin (HZB) observed exotic behaviour from beryllium oxide (BeO) when they bombarded it with high-speed heavy ions: After being shot in this way, the electrons in the BeO appeared "confused", and seemed to completely forget the material properties of their environment. The researchers' measurements show changes in the electronic structure that can be explained by extremely rapid melting around the firing line of the heavy ions. If this interpretation is correct, then this would have to be the fastest melting ever observed. The researchers are publishing their results in Physical Review Letters (DOI:10.1103/Phys.Rev.Lett.105, 187603 (2010)).

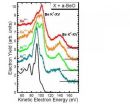

In his experiments, Prof. Dr. Gregor Schiwietz and his team irradiated a beryllium oxide film with high-speed heavy ions of such strong charge that they possessed maximum smashing power. Unlike most other methods, the energy of the heavy ions was chosen so that they would interact chiefly with their outer valence electrons. As heavy ions penetrate into a material, there are typically two effects that occur immediately around the fired ions: the electrons in the immediate surroundings heat up and the atoms become strongly charged. At this point, Auger electrons are emitted, whose energy levels are measurable and show up in a so-called line spectrum. The line spectrum is characteristic for each different material, and normally changes only slightly upon bombardment with heavy ions.

As a world's first, the HZB researchers have now bombarded an ion crystal (BeO), which has insulator properties, with very high-speed heavy ions (xenon ions), upon which they demonstrated a hitherto unknown effect: The line spectrum of the Auger electrons changed drastically – it became "washed out", stretching into higher energies. Together with a team of physicists from Poland, Serbia and Brazil, the researchers observed distinctly metallic signatures from the Auger electrons emitted by the heated BeO material. The Auger electrons appeared to have completely "forgotten" their insulator properties. The researchers see this as clear evidence that the band structure breaks down extremely rapidly when the BeO is bombarded with heavy ions – in less than about 100 femtoseconds (one femtosecond is a millionth of a millionth of a millisecond). This breakdown is triggered by the high electron temperatures of up to 100000 Kelvin. In the long term, however, the material of the otherwise cold solid remains overall intact.

The HZB researchers' results deliver strong evidence of ultra-fast melting processes around the firing line of the heavy ions. This melting is followed by annealing that deletes all permanent signs of the melting process. Prof. Schiwietz hopes to find other ionic crystals that exhibit the same rapid melting process, but in which the annealing process is suppressed. If any are found, then a conceivable application would be programming at femtosecond speeds.

INFORMATION:

Electrons get confused

HZB researchers may have observed the fastest melting of all time

2010-11-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Levels of coumarin in cassia cinnamon vary greatly even in bark from the same tree

2010-11-04

A "huge" variation exists in the amounts of coumarin in bark samples of cassia cinnamon from trees growing in Indonesia, scientists are reporting in a new study. That natural ingredient in the spice may carry a theoretical risk of causing liver damage in a small number of sensitive people who consume large amounts of cinnamon. The report appears in ACS' bi-weekly Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry.

Friederike Woehrlin and colleagues note that cinnamon is the second most popular spice, next to black pepper, in the United States and Europe. Cinnamon, which comes ...

Small materials poised for big impact in construction

2010-11-04

Bricks, blocks, and steel I-beams — step aside. A new genre of construction materials, made from stuff barely 1/50,000th the width of a human hair, is about to debut in the building of homes, offices, bridges, and other structures. And a new report is highlighting both the potential benefits of these nanomaterials in improving construction materials and the need for guidelines to regulate their use and disposal. The report appears in the monthly journal ACS Nano.

Pedro Alvarez and colleagues note that nanomaterials likely will have a greater impact on the construction ...

Transparent conductive material could lead to power-generating windows

2010-11-04

UPTON, NY - Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory and Los Alamos National Laboratory have fabricated transparent thin films capable of absorbing light and generating electric charge over a relatively large area. The material, described in the journal Chemistry of Materials, could be used to develop transparent solar panels or even windows that absorb solar energy to generate electricity.

The material consists of a semiconducting polymer doped with carbon-rich fullerenes. Under carefully controlled conditions, the material self-assembles ...

Video-game technology may speed development of new drugs

2010-11-04

Parents may frown upon video games, but the technology used in the wildly popular games is quietly fostering a revolution in speeding the development of new products and potentially life-saving drugs. That's the topic of an article in the current issue of Chemical & Engineering News (C&EN), ACS' weekly newsmagazine.

C&EN Associate Editor Lauren K. Wolf notes that consumer demand for life-like avatars and interactive scenery has pushed computer firms to develop inexpensive yet sophisticated graphics hardware called graphics processing units, or GPUs. The graphical units ...

PET scans reveal estrogen-producing hotspots in human brain

2010-11-04

UPTON, NY - A study at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory has demonstrated that a molecule "tagged" with a radioactive form of carbon can be used to image aromatase, an enzyme responsible for the production of estrogen, in the human brain. The research, published in the November issue of Synapse, also uncovered that the regions of the brain where aromatase is concentrated may be unique to humans.

"The original purpose of the study was to expand our use of this radiotracer, N-methyl-11C vorozole," said Anat Biegon, a Brookhaven neurobiologist. ...

Scientists develop method to keep surgically-removed prostate tissue alive and 'working' for week

2010-11-04

Scientists at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center, University of Helsinki and Stanford University have developed a technique to keep normal and cancerous prostate tissue removed during surgery alive and functioning normally in the laboratory for up to a week.

The new technique could not only enhance research of prostate biology and cancer, but also hasten the creation of individualized medicines for prostate cancer patients, the investigators say. Previous attempts to culture live prostate tissues resulted in poor viability and lost "tissue architecture," the researchers ...

Rice U. study looks at marketing benefits, pitfalls of customer-satisfaction surveys

2010-11-04

Though designed to enhance customer experiences, post-service customer surveys might actually harm a business's relationships with consumers, according to new research by Rice University professors. The research team found that customers who participate in firm-sponsored surveys delay doing repeat business with that company.

The study finds companies that use immediate follow-up customer surveys or multiple follow-up surveys may open themselves to negative consequences because customers who were satisfied with the specific service they received may jump to the conclusion ...

Multifocal contact lenses may reduce vision for night driving

2010-11-04

A new study suggests that older adults who wear multifocal contact lenses to correct problems with near vision, a very common condition that increases with age, may have greater difficulty driving at night than their counterparts who wear glasses. Age-related problems with near vision, medically termed presbyopia, usually occurs after the age of 40 and results in the inability to focus on objects up close.

According to an article published in Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science ("The Effect of Presbyopic Vision Corrections on Nighttime Driving Performance"), ...

University of Illinois researchers discover potential new virus in switchgrass

2010-11-04

University of Illinois researchers have confirmed the first report of a potential new virus belonging to the genus Marafivirus in switchgrass, a biomass crop being evaluated for commercial cellulosic ethanol production.

The virus is associated with mosaic and yellow streak symptoms on switchgrass leaves. This virus has the potential of reducing photosynthesis and decreasing biomass yield. Members of this genus have been known to cause severe yield losses in other crops. For example, Maize rayado fino virus (MRFV), a type member of the genus, has been reported to cause ...

Physics experiment finds violation of matter/antimatter symmetry

2010-11-04

ANN ARBOR, Mich.---The results of a high-profile Fermilab physics experiment involving a University of Michigan professor appear to confirm strange 20-year-old findings that poke holes in the standard model, suggesting the existence of a new elementary particle: a fourth flavor of neutrino.

The new results go further to describe a violation of a fundamental symmetry of the universe asserting that particles of antimatter behave in the same way as their matter counterparts.

Neutrinos are neutral elementary particles born in the radioactive decay of other particles. The ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Smartphone app can help men last longer in bed

Longest recorded journey of a juvenile fisher to find new forest home

Indiana signs landmark education law to advance data science in schools

A new RNA therapy could help the heart repair itself

The dehumanization effect: New PSU research examines how abusive supervision impacts employee agency and burnout

New gel-based system allows bacteria to act as bioelectrical sensors

The power of photonics

From pioneer to leader: Alex Zhavoronkov chairs precision aging discussion and presents Luminary Award to OpenAI president at PMWC 2026

Bursting cancer-seeking microbubbles to deliver deadly drugs

In a South Carolina swamp, researchers uncover secrets of firefly synchrony

American Meteorological Society and partners issue statement on public availability of scientific evidence on climate change

How far will seniors go for a doctor visit? Often much farther than expected

Selfish sperm hijack genetic gatekeeper to kill healthy rivals

Excessive smartphone use associated with symptoms of eating disorder and body dissatisfaction in young people

‘Just-shoring’ puts justice at the center of critical minerals policy

A new method produces CAR-T cells to keep fighting disease longer

Scientists confirm existence of molecule long believed to occur in oxidation

The ghosts we see

ACC/AHA issue updated guideline for managing lipids, cholesterol

Targeting two flu proteins sharply reduces airborne spread

Heavy water expands energy potential of carbon nanotube yarns

AMS Science Preview: Mississippi River, ocean carbon storage, gender and floods

High-altitude survival gene may help reverse nerve damage

Spatially decoupling active-sites strategy proposed for efficient methanol synthesis from carbon dioxide

Recovery experiences of older adults and their caregivers after major elective noncardiac surgery

Geographic accessibility of deceased organ donor care units

How materials informatics aids photocatalyst design for hydrogen production

BSO recapitulates anti-obesity effects of sulfur amino acid restriction without bone loss

Chinese Neurosurgical Journal reports faster robot-assisted brain angiography

New study clarifies how temperature shapes sex development in leopard gecko

[Press-News.org] Electrons get confusedHZB researchers may have observed the fastest melting of all time