(Press-News.org)

AUDIO:

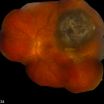

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have identified a gene linked to the spread of melanoma of the eye. Although more research is needed, the researchers...

Click here for more information.

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have identified a gene linked to the spread of eye melanoma.

Although more research is needed, the researchers say the discovery is an important step in understanding why some tumors spread (metastasize) and others don't. They believe the findings could lead to more effective treatments.

Reporting online in the journal Science Express, the team found mutations in a gene called BAP1 in 84 percent of the metastatic eye tumors they studied. In contrast, the mutation was rare in tumors that did not metastasize.

Metastasis is the most common cause of death in cancer patients, yet little is known about how cancer cells evolve the ability to spread to other parts of the body. There is growing evidence that mutations in so-called metastasis suppressor genes may promote the spread of cancer, while having little to do with earlier stages in the life of a tumor. Very few such genes have been identified, but this finding strongly implicates BAP1 as a new member of that small group.

"Scientists and physicians have been waiting for a rational, therapeutic target that we could use to treat high-risk patients," says first author and Washington University ophthalmologist J. William Harbour, MD. "We believe this discovery may provide insights needed to hasten the development of therapies for these patients."

Ocular melanoma, also called uveal melanoma, is the most common eye cancer and the second-most common form of melanoma, striking about 2,000 adults in the United States each year. It can affect people at any age but is most common in patients over 50. The tumors arise from pigment cells, called melanocytes, that reside in the layer below the retina called the uveal tract. Up to half of those with the cancer eventually develop metastatic disease, which is universally fatal.

"The most common site where the cancer spreads is the liver," Harbour says. "If it spreads, it goes to the liver about 90 percent of the time, generally leading to death within months."

To improve survival, scientists need to understand more about what causes the tumor cells to metastasize, according to Harbour, the Paul A. Cibis Distinguished Professor of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, professor of cell biology and of molecular oncology and director of ocular oncology at the Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine.

Harbour and co-investigator Anne M. Bowcock, PhD, professor of genetics of pediatrics and of medicine, have been looking at DNA in tumor cells for clues about why some tumors spread. Tumors had already been grouped into two classes based on gene expression profiles. Class 1 tumors have a low risk of spreading, while class 2 tumors carry a high risk of metastasis. In addition, 90 percent of class 2 tumors have lost a copy of chromosome 3, unlike class 1 tumors, which tend to retain both copies of the chromosome.

In this study, the team looked for differences in genes on chromosome 3 between the cells in class 1 and class 2 tumors. They started with tissue taken from a pair of class 2 tumors.

"We looked for common genetic differences, called polymorphisms, that would unlikely have much of an effect," Bowcock says. "We eliminated those variations and then went back to look at which gene on chromosome 3 had additional alterations. There was one gene, called BAP1, that had mutations in both of the tumors we analyzed."

BAP1 is short for BRCA1-associated protein 1. As it happens, BRCA1 is linked to breast cancer in some women.

"It points, possibly, to a common theme in cancer genetics," Bowcock says. "After identifying mutations in BAP1 in the first two tumors, we went back and looked at DNA from another 29 class 2 tumors, as well as 25 class 1 tumors. And we found that 84 percent of the class 2 tumors had damaging mutations in BAP1. We also found that in most cases, the class 2 tumor cells had only one copy of chromosome 3 – where the gene is located – so patients had only a single copy of the BAP1 gene, and because of damaging mutations, it could not fulfill its proper role in the cell."

It appears that what the gene is supposed to do, Harbour says, is to act as a metastasis suppressor. When it is damaged, the tumor can spread.

"There are several ways this discovery could improve patient care," Harbour says. "If we could detect BAP1 mutations at an earlier stage, for example, we might be able to monitor a patient's blood for detectable melanoma cells as an early sign that they're developing metastatic disease."

He also says a better understanding of the normal role of the BAP1 protein could provide powerful insights into ways to therapeutically target eye tumors that are likely to spread. He and Bowcock already are beginning those studies.

"We know now that BAP1 is the big player in class 2 tumors, but there are other players, too," Bowcock adds. "We'd also like to understand what other genes are mutated in class 1 tumors and why they don't metastasize."

Bowcock and Harbour identified a single class 1 tumor with a BAP1 mutation. One possible explanation for that finding may be that the tumor was evolving into a class 2 tumor.

In a second series of experiments, the researchers found that if they put ocular melanoma cells in culture and depleted their supply of BAP1, the cells began to change in appearance and to resemble class 2 tumors in just five days.

"Now we're trying to knock down BAP1 levels for weeks to months and find out whether we start to see some of the chromosomal changes that are present in class 2 tumors," Harbour says.

He says it remains unclear whether class 1 and class 2 tumors are different from their very inception or whether ocular melanoma tumors begin their existence as class 1 tumors and then, eventually, develop cells with BAP1 mutations.

"We have hints, both from experimental work and from patient samples, that the latter scenario is more likely, that the tumors start off as class 1 and evolve into class 2 tumors," Harbour explains. "But that is still somewhat speculative, and we'll need to do more experiments to test that hypothesis."

The BAP1 mutation represents only the second common genetic mutation ever reported in ocular melanoma, and it is the only mutation linked to metastasis in this type of cancer.

"This finding will fundamentally alter the concepts and methodologies employed in patient management and in research in this field," Bowcock says. "For example, it should lead to new diagnostic tests to distinguish benign from malignant growths of the eye, which could avoid thousands of needless, vision-threatening treatments each year while allowing earlier interventions in the few patients who truly harbor a malignant melanoma. In addition, the insights gained from this research into how BAP1 functions at a molecular level might pave the way for innovative new therapeutic approaches to the previously recalcitrant problem of metastatic disease."

INFORMATION:

Harbour JW, Onken MD, Roberson EDO, Duan S, Cao L, Worley LA, Council ML, Matatall KA, Helms C, Bowcock AM. Frequent mutation of BAP1 in metastasizing uveal melanoma. Science Express, science.1194472

This research was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute, National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health, Barnes-Jewish Hospital Foundation, Kling Family Foundation, Tumori Foundation, Horncrest Foundation and Research to Prevent Blindness.

J. William Harbour, MD, and Washington University may receive future income based on the university's licensing of a related technology to Castle Biosciences Inc.

Washington University School of Medicine's 2,100 employed and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient care institutions in the nation, currently ranked fourth in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.

Siteman Cancer Center is the only NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center within a 240-mile radius of St. Louis. Siteman Cancer Center is composed of the combined cancer research and treatment programs of Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine.

Gene identified for spread of deadly melanoma

2010-11-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Missouri Botanical Garden researchers discover 8 new species in Boliva national parks

2010-11-05

(ST. LOUIS): Botanists at the Missouri Botanical Garden have described eight new plant species collected in the Madidi National Park and surrounding areas located on the eastern slopes of the Andes in northern Bolivia. The new species are from several different genera and families and are published in a recent edition of the Missouri Botanical Garden journal Novon.

Missouri Botanical Garden scientists and colleagues from the National Herbarium in La Paz, Bolivia describe Prestonia leco, Passiflora madidiana, Siphoneugena minima, Siphoneugena glabrata, Hydrocotyle apolobambensis, ...

Polar bears can't eat geese into extinction

2010-11-05

As the Arctic warms, a new cache of resources—snow goose eggs—may help sustain the polar bear population for the foreseeable future. In a new study published in an early online edition of Oikos, researchers affiliated with the Museum show that even large numbers of hungry bears repeatedly raiding nests over many years would have a difficult time eliminating all of the geese because of a mismatch in the timing of bear arrival on shore and goose egg incubation.

"There have been statements in popular literature indicating that polar bears can extirpate snow geese quickly ...

Pigs reveal secrets: New research shines light on Quebec industry

2010-11-05

Which are the best pieces of pork, what their texture is, how moist they are – the secrets pigs keep from even the most skilled butchers – are about to be revealed, thanks to a sophisticated new technique that has been developed by McGill University researchers in conjunction with Agriculture Canada and the pork industry. "This is about giving industry workers better tools to do their job," explained Dr. Michael Ngadi of McGill's Department of Bioresource Engineering. "Computer-aided analysis of meat will result in higher-quality jobs, optimal production, and exports that ...

Hard work improves the taste of food, Johns Hopkins study shows

2010-11-05

It's commonly accepted that we appreciate something more if we have to work hard to get it, and a Johns Hopkins University study bears that out, at least when it comes to food.

The study seems to suggest that hard work can even enhance our appreciation for fare we might not favor, such as the low-fat, low calorie variety. At least in theory, this means that if we had to navigate an obstacle course to get to a plate of baby carrots, we might come to prefer those crunchy crudités over the sweet, gooey Snickers bars or Peanut M&Ms more easily accessible via the office vending ...

Burning pain and itching governed by same nerve cells

2010-11-05

There are disorders and conditions that entail increased itching and can be extremely troublesome for those suffering from it. The mechanisms behind itching are not well understood today. For one thing, what is it about scratching that relieves itching?

In the current study, which was performed on mice, the research team led by Professor Klas Kullander at the Department of Neuroscience examined the nerve cells that transfer heat pain. When these nerve cells had lost its capacity to signal, the mice reacted less to heat, as expected, but surprisingly they also started ...

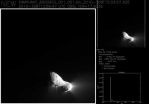

UMD-led deep impact spacecraft successfully flies by comet Hartley 2

2010-11-05

COLLEGE PARK, Md. – The University of Maryland-led EPOXI mission successfully flew by comet Hartley 2 at 10 a.m. EDT today, and the spacecraft has begun returning images. Hartley 2 is the fifth comet nucleus visited by any spacecraft and the second one visited by the Deep Impact spacecraft.

Scientists and mission controllers are studying never-before-seen images of Hartley 2 appearing on their computer terminal screens. See images at: http://epoxi.umd.edu/

"We are all holding our breath to see what discoveries await us in the observations near closest approach," said ...

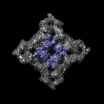

Researchers unlock the secret of bacteria's immune system

2010-11-05

Quebec City, November 4, 2010—A team of Université Laval and Danisco researchers has just unlocked the secret of bacteria's immune system. The details of the discovery, which may eventually make it possible to prevent certain bacteria from developing resistance to antibiotics, are presented in today's issue of the scientific journal Nature.

The team led by Professor Sylvain Moineau of Université Laval's Department of Biochemistry, Microbiology, and Bioinformatics showed that this mechanism, called CRISPR/Cas, works by selecting foreign DNA segments and inserting them ...

A 'brand' new world: Attachment runs thicker than money

2010-11-05

Can you forge an emotional bond with a brand so strong that, if forced to buy a competitor's product, you suffer separation anxiety? According to a new study from the USC Marshall School of Business, the answer is yes. In fact, that bond can be strong enough that consumers are willing to sacrifice time, money, energy and reputation to maintain their attachment to that brand.

"Brand Attachment and Brand Attitude Strength: Conceptual and Empirical Differentiation of Two Critical Brand Equity Drivers," a study published in the November issue of the Journal of Marketing, ...

X-rays offer first detailed look at hotspots for calcium-related disease

2010-11-05

Menlo Park, Calif.—Calcium regulates many critical processes within the body, including muscle contraction, the heartbeat, and the release of hormones. But too much calcium can be a bad thing. In excess, it can lead to a host of diseases, such as severe muscle weakness, a fatal reaction to anesthesia or sudden cardiac death.

Now, using intense X-rays from the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) at the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, researchers have determined the detailed structure of a key part of the ryanodine receptor, a ...

Colonic navigation

2010-11-05

Nanoparticles could help smuggle drugs into the gut, according to a study published this month in the International Journal of Nanotechnology.

There are several drugs that would have more beneficial therapeutic effects if they could be targeted at absorption by the lower intestine. However, in order to target the colon for treating colon cancer for instance, medication delivered by mouth must surmount several barriers including stomach acidity, binding to mucus layers, rapid clearance from the gut, and premature uptake by cells higher up the gastrointestinal tract. Being ...