(Press-News.org) A genetic mechanism that controls the production of a large spike-like protein on the surface of Staphylococcus aureus (staph) bacteria alters the ability of the bacteria to form clumps and to cause disease, according to a new University of Iowa study.

The new study is the first to link this genetic mechanism to the production of the giant surface protein and to clumping behavior in bacteria. It is also the first time that clumping behavior has been associated with endocarditis, a serious infection of heart valves that kills 20,000 Americans each year. The findings were published in the Dec. 2103 issue of the journal PLOS Pathogens.

Under normal conditions, staph bacteria interact with proteins in human blood to form aggregates, or clumps. This clumping behavior has been associated with pathogenesis -- the ability of bacteria to cause disease. However, the mechanisms that control clumping are not well understood.

In the process of investigating how staph bacteria regulate cell-to-cell interactions, researchers at the UI Carver College of Medicine discovered a mutant strain of staph that does not clump at all in the presence of blood proteins.

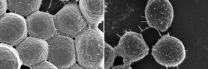

Further investigation revealed that the clumping defect is due to disruption of a genetic signaling mechanism used by bacteria to sense and respond to their environment. The study shows that when the mechanism is disrupted, the giant surface protein is overproduced -- giving the cells a spiny, or "porcupine-like" appearance -- and the bacteria lose their ability to form clumps.

Importantly, the researchers led by Alexander Horswill, PhD, associate professor of microbiology, found that this clumping defect also makes the bacteria less dangerous in an experimental model of the serious staph infection, endocarditis.

Specifically, the team showed that wild type bacteria cause much larger vegetations (aggregates of bacteria) on the heart valves and are more deadly than the mutant bacteria, which are unable to form clumps. The experimental model of the disease was a good parallel to the team's test tube experiments.

"The mutant bacteria that don't clump in test tube experiments, don't form vegetations on the heart valves," Horswill explains.

The team then created a version of the mutant bacteria that was also unable to make the giant surface protein. This strain regained the ability of form clumps and also partially regained its ability to cause disease, suggesting that the surface protein is at least partly responsible for both preventing clump formation and for reducing pathogenesis.

"Our study suggests that clumping could be a target for therapy," says Horswill. "If we could find drugs that block clumping, I think they would be potentially really useful for blocking staph infections."

Staph bacteria are the most significant cause of serious infectious disease in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The bacteria are responsible for life-threatening conditions, including endocarditis, pneumonia, toxic shock, and sepsis. A better understanding of how staph bacteria causes disease may help improve treatment.

The team is now using screening methods to find small molecules that can block clumping. Such molecules will allow the researchers to investigate the clumping mechanism more thoroughly and may also point to therapies that might reduce the illness caused by staph infections.

INFORMATION:

The research was partially supported by grant funding from the National Institutes of Health (AI083211 and AI157153).

In addition to Horswill, the research team included Jeffrey Boyd, PhD, a former post doctoral researcher at the UI, whose early work initiated the study, and Patrick Schlievert, PhD, UI professor and chair of microbiology. UI scientists Jennifer Walker, Heidi Crosby, Adam Spaulding, Wilmara Salgado-Pabon, Cheryl Malone, and Carolyn Rosenthal were also part of the research team.

Prickly protein

Production of an exceptionally large surface protein prevents bacteria from forming clumps and reduces their ability to cause disease

2014-02-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

NASA study points to infrared-herring in apparent Amazon green-up

2014-02-06

For the past eight years, scientists have been working to make sense of why some satellite data seemed to show the Amazon rain forest "greening-up" during the region's dry season each year from June to October. The green-up indicated productive, thriving vegetation in spite of limited rainfall.

Now, a new NASA study published today in the journal Nature shows that the appearance of canopy greening is not caused by a biophysical change in Amazon forests, but instead by a combination of shadowing within the canopy and the way that satellite sensors observe the Amazon during ...

Valentine's Day advice: Don't let rocky past relations with parents spoil your romance

2014-02-06

University of Alberta relationship researcher Matt Johnson has some Valentine's Day advice for anybody who's had rocky relations with their parents while growing up: don't ...

Falcon feathers pop-up during dive

2014-02-06

Similar to wings and fins with self-adaptive flaps, the feathers on a diving peregrine falcon's feathers may pop-up during high speed dives, according to a study published in PLOS ONE on February 5, 2014 by Benjamin Ponitz from the Institute of Mechanics ...

New, high-tech prosthetics and orthotics offer active life-style for users

2014-02-06

TAMPA, Fla. (Feb. 5, 2014) – Thanks to advanced technologies, those who wear prosthetic and orthotic devices ...

University of Montana research shows converting land to agriculture reduces carbon uptake

2014-02-06

MISSOULA – University of Montana researchers examined the impact that converting natural land to cropland has on global vegetation growth, as measured by satellite-derived ...

Bacterial fibers critical to human and avian infection

2014-02-06

Escherichia coli—a friendly and ubiquitous bacterial resident in the guts of humans and other animals—may occasionally colonize regions outside the intestines. There, it can have serious consequences for health, ...

Study suggests whole diet approach to lower CV risk has more evidence than low-fat diets

2014-02-06

Philadelphia, PA, February 5, 2014 – A study published in The American Journal of Medicine ...

Bundles of nerves and arteries provide wealth of new stem cell information

2014-02-06

A new Ostrow School of Dentistry of ...

Birds of a different color

2014-02-06

SALT LAKE CITY, Feb. 6, 2014 – Scientists at the University of Utah identified mutations in three key genes that determine feather color in domestic rock pigeons. The same genes control pigmentation ...

Pacific salmon inherit a magnetic sense of direction

2014-02-06

Even young hatchery salmon with no prior experience of the world outside will orient themselves according to the Earth's magnetic field in the direction of the marine feeding grounds frequented by their ancestors. These findings, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

SfN announces Early Career Policy Ambassadors Class of 2026

Spiritual practices strongly associated with reduced risk for hazardous alcohol and drug use

Novel vaccine protects against C. diff disease and recurrence

An “electrical” circadian clock balances growth between shoots and roots

Largest study of rare skin cancer in Mexican patients shows its more complex than previously thought

Colonists dredged away Sydney’s natural oyster reefs. Now science knows how best to restore them.

Joint and independent associations of gestational diabetes and depression with childhood obesity

Spirituality and harmful or hazardous alcohol and other drug use

New plastic material could solve energy storage challenge, researchers report

Mapping protein production in brain cells yields new insights for brain disease

Exposing a hidden anchor for HIV replication

Can Europe be climate-neutral by 2050? New monitor tracks the pace of the energy transition

Major heart attack study reveals ‘survival paradox’: Frail men at higher risk of death than women despite better treatment

Medicare patients get different stroke care depending on plan, analysis reveals

Polyploidy-induced senescence may drive aging, tissue repair, and cancer risk

Study shows that treating patients with lifestyle medicine may help reduce clinician burnout

Experimental and numerical framework for acoustic streaming prediction in mid-air phased arrays

Ancestral motif enables broad DNA binding by NIN, a master regulator of rhizobial symbiosis

Macrophage immune cells need constant reminders to retain memories of prior infections

Ultra-endurance running may accelerate aging and breakdown of red blood cells

Ancient mind-body practice proven to lower blood pressure in clinical trial

SwRI to create advanced Product Lifecycle Management system for the Air Force

Natural selection operates on multiple levels, comprehensive review of scientific studies shows

Developing a national research program on liquid metals for fusion

AI-powered ECG could help guide lifelong heart monitoring for patients with repaired tetralogy of fallot

Global shark bites return to average in 2025, with a smaller proportion in the United States

Millions are unaware of heart risks that don’t start in the heart

What freezing plants in blocks of ice can tell us about the future of Svalbard’s plant communities

A new vascularized tissueoid-on-a-chip model for liver regeneration and transplant rejection

Augmented reality menus may help restaurants attract more customers, improve brand perceptions

[Press-News.org] Prickly proteinProduction of an exceptionally large surface protein prevents bacteria from forming clumps and reduces their ability to cause disease