(Press-News.org) ANN ARBOR—Dengue fever and West Nile fever are mosquito-borne diseases that affect hundreds of millions of people worldwide each year, but there is no vaccine against either of the related viruses.

A team of scientists at the University of Michigan and Purdue University has discovered a key aspect both to how the viruses replicate in the cells of their host and how they manipulate the immune system as they spread.

In a study scheduled for online publication Feb. 6 in the journal Science, researchers led by Janet Smith of the U-M Life Sciences Institute describe for the first time the structure of a protein that helps the viruses replicate and spread infection.

"Seeing the design of this key protein provides a target for a potential vaccine or even a therapeutic drug," Smith said.

The protein, NS1, is produced inside infected cells, where it plays a key role in replication of the virus. NS1 is also released into the bloodstream, where it may help disguise the infection from the patient's immune system and may play a role in the hemorrhage that is seen in severe dengue virus infection.

Dengue and West Nile viruses are members of the flavivirus family, which includes yellow fever and several encephalitis viruses. Dengue, which emerged as a public health problem in the 1950s, is endemic in the majority of countries along the equatorial belt and has been reported in the southern United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. West Nile virus first appeared in North America in 1999 and rapidly spread to all 48 contiguous states, with nearly 3,000 cases reported in 2013. Dengue fever affects as many as 400 million people worldwide each year.

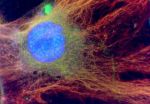

Smith and her colleagues created images of the protein using X-ray crystallography, a technique that uses X-ray beams to map the positions of atoms in a crystal.

"Isolating the protein in order to study it has been a challenge for researchers," Smith said. "Once we discovered how to do that, it crystallized beautifully."

Researchers have pursued this protein for years because both its role in replication and its unique release into the bloodstream mark it as a target for treatment of infection, said Richard Kuhn, professor and department head of biological sciences and the Gerald and Edna Mann Director of the Bindley Bioscience Center at Purdue University.

"Having the structure of NS1 is a huge advance in understanding, and using, the protein to our advantage," said Kuhn, who led the Purdue team involved in the work. "Understanding how the protein is designed provides an easier pathway to understanding its roles in the virus life cycle. We now know which portions of the protein to target in drug development to shut it down and stop the progression of infection."

The researchers discovered that NS1 has a 3-D structure with two distinct sides, one facing the replication system of the virus inside cells it infects and the other facing the immune system outside infected cells.

"The two faces of NS1 define the regions responsible for its two major functions," Smith said. "This understanding will guide future research into dissecting and targeting these regions in disease treatment or prevention."

Dengue presents specific challenges for researchers working on developing a vaccine. The illness is caused by any one of four related viruses transmitted by mosquitoes. People infected by one type usually develop mild flu-like symptoms, although severe muscle and joint pain is common.

However, if subsequently bitten by a mosquito carrying another of the four types, the second exposure can lead to serious illness and death. This one-two punch greatly complicates development of a vaccine, Smith said.

"We don't want to prime people for severe dengue disease by delivering their first exposure to the virus in the form of a vaccine," she said.

Developing a clearer picture of how the NS1 protein interacts with the immune system and influences disease may pave the way for researchers to develop a vaccine that protects people—without inadvertently increasing their risk.

"Now that we understand the structure of the protein, we can manipulate it to probe specific functions," Kuhn said. "This could lead to a way to prevent any harmful priming of the immune system."

The research required the different expertise of a range of scientists, Smith said. First, researchers in the Smith lab crystallized the protein at LSI's Center for Structural Biology. Then they put the crystals in an X-ray beam at the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory in Illinois to create a map of the protein. They used the map to build a 3-D structure in atomic detail.

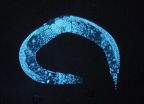

The lab of Georgios Skiniotis, also at U-M's LSI, used electron microscopy to show how NS1 associates with membranes of the infected cell, which the researchers suspected would be associated with both virus replication and immune evasion. The Kuhn lab at Purdue showed how that membrane association is critical for replication of the virus inside cells.

"We're now collaborating with the Purdue virologists to understand exactly how the two faces of NS1 help the virus survive and thrive in patients," Smith said. "These studies are the next steps toward a vaccine or an antiviral drug."

INFORMATION:

Other authors of the paper were David Akey, W. Clay Brown, James DelProposto, Somnath Dutta, Thomas Jurkiw, Jamie Konwerski at the U-M Life Sciences Institute; Georgios Skiniotis at the Life Sciences Institute and U-M Department of Biological Chemistry; Joyce Jose at Purdue's Department of Biological Sciences; and Craig Ogata at Argonne National Laboratory.

Support for the research was provided by the National Institutes of Health, Martha L. Ludwig Professorship of Protein Structure and Function, Pew Scholar Program in Biomedical Sciences, and Perrigo Undergraduate Summer Fellowship. X-ray beam lines were supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences and National Cancer Institute.

Smith is a research professor at the U-M Life Sciences Institute, where her laboratory is located and her research is conducted. She is also the director of the Center for Structural Biology, housed at LSI, and the Margaret J. Hunter Collegiate Professor of Life Sciences, Department of Biological Chemistry, U-M Medical School.

Janet Smith: http://www.lsi.umich.edu/people/janet-smith

U-M Life Sciences Institute: http://lsi.umich.edu

Crystallography and structural biology at U-M: http://bit.ly/1bnkOVL

Decoding dengue and West Nile: Researchers take steps toward control of health proble

2014-02-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Autism: Birth hormone may control the expression of the syndrome in animals

2014-02-06

This news release is available in French.

The scientific community agrees that autism has its origins in early life—foetal and/or postnatal. The team led by Yehezkel Ben-Ari, Inserm Emeritus Research Director at the Mediterranean Institute of Neurobiology (INMED), has made a breakthrough in the understanding of the disorder. In an article published in Science, the researchers demonstrate that chloride levels are elevated in the neurons of mice used in an animal model of autism, and remain at abnormal levels from birth. These results corroborate the success obtained ...

Opening 'the X-files' helped researchers to understand why women and men differ in height

2014-02-06

Researchers from the University of Helsinki analyzed thoroughly the commonly occurring genetic variation in chromosome X, one of the two sex-determining chromosomes, in almost 25,000 Northern European individuals with diverse health-related information available. The aim of the study was to find genetic factors that could explain individual differences in several traits, including BMI, height, blood pressure and lipid levels. In addition, the researchers also investigated whether the X chromosome would contribute to some of the well-known differences between men and women ...

Theorists predict new forms of exotic insulating materials

2014-02-06

CAMBRIDGE, Mass-- Topological insulators — materials whose surfaces can freely conduct electrons even though their interiors are electrical insulators — have been of great interest to physicists in recent years because of unusual properties that may provide insights into quantum physics. But most analysis of such materials has had to rely on highly simplified models.

Now, a team of researchers at MIT has performed a more detailed analysis that hints at the existence of six new kinds of topological insulators. The work also predicts the materials' physical properties in ...

Researchers pinpoint protein associated with canine hereditary ataxia

2014-02-06

Researchers from North Carolina State University have found a link between a mutation in a gene called RAB 24 and an inherited neurodegenerative disease in Old English sheepdogs and Gordon setters. The findings may help further understanding of neurodegenerative diseases and identify new treatments for both canine and human sufferers.

Hereditary ataxias are an important group of inherited neurodegenerative diseases in people. This group of diseases is the third most common neurodegenerative movement disorder after Parkinson's and Huntington's diseases.

In people with ...

Nutritional supplement improves cognitive performance in older adults, study finds

2014-02-06

Tampa, FL (Feb. 6, 2014) – Declines in the underlying brain skills needed to think, remember and learn are normal in aging. In fact, this cognitive decline is a fact of life for most older Americans.

Therapies to improve the cognitive health of older adults are critically important for lessening declines in mental performance as people age. While physical activity and cognitive training are among the efforts aimed at preventing or delaying cognitive decline, dietary modifications and supplements have recently generated considerable interest.

Now a University of South ...

Immune system 'overdrive' in pregnant women puts male child at risk for brain disorders

2014-02-06

Johns Hopkins researchers report that fetal mice — especially males — show signs of brain damage that lasts into their adulthood when they are exposed in the womb to a maternal immune system kicked into high gear by a serious infection or other malady. The findings suggest that some neurologic diseases in humans could be similarly rooted in prenatal exposure to inflammatory immune responses.

In a report on the research published online last week in the journal Brain, Behavior and Immunity, the investigators say that the part of the brain responsible for memory and spatial ...

Source of chlamydia reinfections may be GI tract

2014-02-06

The current standard of care treatment for chlamydia sometimes fails to eradicate the disease, according to a review published ahead of print in Infection and Immunity, and the culprit may be in the gut.

Chlamydia trachomatis not only infects the reproductive tract, but abides persistently—though benignly—in the gastrointestinal tract. There it remains even after eradication from the genitals by the antibiotic, azithromycin, says first author Roger Rank, of the Arkansas Children's Research Institute, Little Rock. And that reservoir is likely a source of the all-too-common ...

Scientific review points to supplement users engaging in a pattern of healthy habits

2014-02-06

Washington, D.C., February 6, 2014—Dietary supplement users take these products as just one component of a larger effort to develop a healthier lifestyle, according to a newly published review in Nutrition Journal, a peer-reviewed scientific publication. The review, "Health Habits and Other Characteristics of Supplement Users" (Nutrition Journal.2014, 13:14), co-authored by Council for Responsible Nutrition (CRN) consultant Annette Dickinson, Ph.D., and CRN's senior vice president, scientific and regulatory affairs, Duffy MacKay, N.D., examined data from 20 peer-reviewed ...

Global regulator of mRNA editing found

2014-02-06

An international team of researchers, led by scientists from the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine and Indiana University, have identified a protein that broadly regulates how genetic information transcribed from DNA to messenger RNA (mRNA) is processed and ultimately translated into the myriad of proteins necessary for life.

The findings, published today in the journal Cell Reports, help explain how a relatively limited number of genes can provide versatile instructions for making thousands of different messenger RNAs and proteins used by cells in ...

Toxin from brain cells triggers neuron loss in human ALS model

2014-02-06

NEW YORK, NY (February 6, 2014) — In most cases of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), or Lou Gehrig's disease, a toxin released by cells that normally nurture neurons in the brain and spinal cord can trigger loss of the nerve cells affected in the disease, Columbia researchers reported today in the online edition of the journal Neuron.

The toxin is produced by star-shaped cells called astrocytes and kills nearby motor neurons. In ALS, the death of motor neurons causes a loss of control over muscles required for movement, breathing, and swallowing. Paralysis and death ...