(Press-News.org) NEW YORK, NY (February 6, 2014) — In most cases of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), or Lou Gehrig's disease, a toxin released by cells that normally nurture neurons in the brain and spinal cord can trigger loss of the nerve cells affected in the disease, Columbia researchers reported today in the online edition of the journal Neuron.

The toxin is produced by star-shaped cells called astrocytes and kills nearby motor neurons. In ALS, the death of motor neurons causes a loss of control over muscles required for movement, breathing, and swallowing. Paralysis and death usually occur within 3 years of the appearance of first symptoms.

The report follows the researchers' previous study, which found similar results in mice with a rare, genetic form of the disease, as well as in a separate study from another group that used astrocytes derived from patient neural progenitor cells. The current study shows that the toxins are also present in astrocytes taken directly from ALS patients.

"I think this is probably the best evidence we can get that what we see in mouse models of the disease is also happening in human patients," said the study's senior author, Serge Przedborski, MD, PhD, the Page and William Black Professor of Neurology (in Pathology and Cell Biology), Vice Chair for Research in the Department of Neurology, and co-director of Columbia's Motor Neuron Center.

The findings also are significant because they apply to the most common form of ALS, which affects about 90 percent of patients. Scientists do not know why ALS develops in these patients; the other 10 percent of patients carry one of 27 genes known to cause the disease.

"Now that we know that the toxin is common to most patients, it gives us an impetus to track down this factor and learn how it kills the motor neurons," Dr. Przedborski said. "Its identification has the potential to reveal new ways to slow down or stop the destruction of the motor neurons."

In the study, Dr. Przedborski and study co-authors Diane Re, PhD, and Virginia Le Verche, PhD, associate research scientists, removed astrocytes from the brain and spinal cords of six ALS patients shortly after death and placed the cells in petri dishes next to healthy motor neurons. Because motor neurons cannot be removed from human subjects, they had been generated from human embryonic stem cells in the Project A.L.S./Jenifer Estess Laboratory for Stem Cell Research, also at CUMC.

Within two weeks, many of the motor neurons had shrunk and their cell membranes had disintegrated; about half of the motor neurons in the dish had died. Astrocytes removed from people who died from causes other than ALS had no effect on the motor neurons. Nor did other types of cells taken from ALS patients.

The researchers confirmed that the cause of the motor neurons' death was a toxin released into the environment by immersing healthy motor neurons in the astrocytes' culture media. The presence of the media, even without astrocytes, killed the motor neurons.

How the Toxin Triggers Motor Neuron Death

The researchers have not yet identified the toxin released by the astrocytes. But they did discover the nature of the neuronal death process triggered by the toxin.The toxin triggers a biochemical cascade in the motor neurons that essentially causes them to undergo a controlled cellular explosion.

Drs. Przedborski, Re, and Le Verche found that they could prevent astrocyte-triggeredmotor neuron death by inhibiting one of the key components of this molecular cascade.

These findings may lead to a way to prevent motor neuron death in patients and potentially prolong life. But the therapeutic potential of such inhibition is far from clear. "For example, we don't know if this would leave patients with living but dysfunctional neurons," Dr. Przedborski said. The researchers are now testing the idea of inhibition in animal models of ALS.

New Human Cell Model of ALS Will Speed Identification of Potential Therapies

The development of new therapies for ALS has been disappointing, with more than 30 clinical trials ending with no new treatments since the 1995 FDA approval of riluzole.

The lack of progress may be partly because animal models used to study ALS do not completely recreate the human disease. The new all-human cell model of ALS created for the current study may improve scientists' ability to identify useful drug targets, particularly for the most common form of the disease.

"Although there are many neurodegenerative disorders, only for a handful do we have access to a simplified model that is relevant to the disease and can therefore potentially be used for high-throughput drug screening. So this model is quite special," Dr. Przedborski said. "Here we have a spontaneous disease phenotype triggered by the relevant tissue that causes human illness. That's one important thing. The other important thing is that this model is derived entirely from human elements. This is probably the closest, most natural model of human ALS that we can get in a dish."

INFORMATION:

The paper is titled: "Necroptosis drives motor neuron death in models of both sporadic and familial ALS." Other contributors are: from CUMC, Changhao Yu, Kristin Politi, Sudarshan Phani, Burcin Ikiz, Lucas Hoffman, Tetsuya Nagata, Dimitra Papadimitriou, Peter Nagy, Hiroshi Mitsumoto, Shingo Kariya; Martijn Koolen (CUMC and University of Amsterdam); Mackenzie Amoroso, Hynek Wichterle, and Christopher Henderson (CUMC and Project A.L.S.).

The authors declare no financial or other conflicts of interest.

The research was supported by the NIH (grants U42RR006042, NS062180, NS064191, NS042269, NS072182, NS062055, NS078614, ES009089, TR000082, and ES016348), the U.S. Department of Defense (W81XWH-08-1-0522 and W81XWH-12-1-0431), Project A.L.S., P2ALS, the ALS Association, the Muscular Dystrophy Association/Wings Over Wall Street, the Parkinson's Disease Foundation, Midwinter Night's Dream Summer Research Program, the NIEHS Center of Northern Manhattan, and the Philippe Foundation.

Columbia University Medical Center provides international leadership in basic, preclinical, and clinical research; medical and health sciences education; and patient care. The medical center trains future leaders and includes the dedicated work of many physicians, scientists, public health professionals, dentists, and nurses at the College of Physicians and Surgeons, the Mailman School of Public Health, the College of Dental Medicine, the School of Nursing, the biomedical departments of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, and allied research centers and institutions. Columbia University Medical Center is home to the largest medical research enterprise in New York City and State and one of the largest faculty medical practices in the Northeast. For more information, visit cumc.columbia.edu or columbiadoctors.org.

Toxin from brain cells triggers neuron loss in human ALS model

Study in human cells may improve ability to identify useful drug targets

2014-02-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New insight into an emerging genome-editing tool

2014-02-06

The potential is there for bacteria and other microbes to be genetically engineered to perform a cornucopia of valuable goods and services, from the production of safer, more effective medicines and clean, green, sustainable fuels, to the clean-up and restoration of our air, water and land. Cells from eukaryotic organisms can also be modified for research or to fight disease. To achieve these and other worthy goals, the ability to precisely edit the instructions contained within a target's genome is a must. A powerful new tool for genome editing and gene regulation has ...

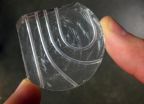

Credit card-sized device could analyze biopsy, help diagnose pancreatic cancer in minutes

2014-02-06

Pancreatic cancer is a particularly devastating disease. At least 94 percent of patients will die within five years, and in 2013 it was ranked as one of the top 10 deadliest cancers.

Routine screenings for breast, colon and lung cancers have improved treatment and outcomes for patients with these diseases, largely because the cancer can be detected early. But because little is known about how pancreatic cancer behaves, patients often receive a diagnosis when it's already too late.

University of Washington scientists and engineers are developing a low-cost device that ...

UI researchers evaluate best weather forecasting models

2014-02-06

Two University of Iowa researchers recently tested the ability of the world's most advanced weather forecasting models to predict the Sept. 9-16, 2013 extreme rainfall that caused severe flooding in Boulder, Colo.

The results, published in the December 2013 issue of the journal Geophysical Research Letters, indicated the forecasting models generally performed well, but also left room for improvement.

David Lavers and Gabriele Villarini, researchers at IIHR—Hydroscience and Engineering, a world-renowned UI research facility, evaluated rainfall forecasts from eight different ...

Nanoparticle pinpoints blood vessel plaques

2014-02-06

A team of researchers, led by scientists at Case Western Reserve University, has developed a multifunctional nanoparticle that enables magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to pinpoint blood vessel plaques caused by atherosclerosis. The technology is a step toward creating a non-invasive method of identifying plaques vulnerable to rupture–the cause of heart attack and stroke—in time for treatment.

Currently, doctors can identify only blood vessels that are narrowing due to plaque accumulation. A doctor makes an incision and slips a catheter inside a blood vessel in the arm, ...

Loose coupling between calcium channels and sensors

2014-02-06

This news release is available in German. Information transmission at the synapse between neurons is a highly complex, but at the same time very fast, series of events. When a voltage change, the so-called action potential, reaches the synaptic terminal in the presynaptic neuron, calcium flows through voltage-gated calcium channels into the presynaptic neuron. This influx leads to a rise in the intracellular calcium concentration. Calcium then binds to a calcium sensor in the presynaptic terminal, which in turn triggers the release of vesicles containing neurotransmitters ...

US lead in science and technology shrinking

2014-02-06

The United States' (U.S.) predominance in science and technology (S&T) eroded further during the last decade, as several Asian nations--particularly China and South Korea--rapidly increased their innovation capacities. According to a report released today by the National Science Board (NSB), the policy making body of the National Science Foundation (NSF) and an advisor to the President and Congress, the major Asian economies, taken together, now perform a larger share of global R&D than the U.S., and China performs nearly as much of the world's high-tech manufacturing as ...

Prickly protein

2014-02-06

A genetic mechanism that controls the production of a large spike-like protein on the surface of Staphylococcus aureus (staph) bacteria alters the ability of the bacteria to form clumps and to cause disease, according to a new University of Iowa study.

The new study is the first to link this genetic mechanism to the production of the giant surface protein and to clumping behavior in bacteria. It is also the first time that clumping behavior has been associated with endocarditis, a serious infection of heart valves that kills 20,000 Americans each year. The findings were ...

NASA study points to infrared-herring in apparent Amazon green-up

2014-02-06

For the past eight years, scientists have been working to make sense of why some satellite data seemed to show the Amazon rain forest "greening-up" during the region's dry season each year from June to October. The green-up indicated productive, thriving vegetation in spite of limited rainfall.

Now, a new NASA study published today in the journal Nature shows that the appearance of canopy greening is not caused by a biophysical change in Amazon forests, but instead by a combination of shadowing within the canopy and the way that satellite sensors observe the Amazon during ...

Valentine's Day advice: Don't let rocky past relations with parents spoil your romance

2014-02-06

University of Alberta relationship researcher Matt Johnson has some Valentine's Day advice for anybody who's had rocky relations with their parents while growing up: don't ...

Falcon feathers pop-up during dive

2014-02-06

Similar to wings and fins with self-adaptive flaps, the feathers on a diving peregrine falcon's feathers may pop-up during high speed dives, according to a study published in PLOS ONE on February 5, 2014 by Benjamin Ponitz from the Institute of Mechanics ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

SfN announces Early Career Policy Ambassadors Class of 2026

Spiritual practices strongly associated with reduced risk for hazardous alcohol and drug use

Novel vaccine protects against C. diff disease and recurrence

An “electrical” circadian clock balances growth between shoots and roots

Largest study of rare skin cancer in Mexican patients shows its more complex than previously thought

Colonists dredged away Sydney’s natural oyster reefs. Now science knows how best to restore them.

Joint and independent associations of gestational diabetes and depression with childhood obesity

Spirituality and harmful or hazardous alcohol and other drug use

New plastic material could solve energy storage challenge, researchers report

Mapping protein production in brain cells yields new insights for brain disease

Exposing a hidden anchor for HIV replication

Can Europe be climate-neutral by 2050? New monitor tracks the pace of the energy transition

Major heart attack study reveals ‘survival paradox’: Frail men at higher risk of death than women despite better treatment

Medicare patients get different stroke care depending on plan, analysis reveals

Polyploidy-induced senescence may drive aging, tissue repair, and cancer risk

Study shows that treating patients with lifestyle medicine may help reduce clinician burnout

Experimental and numerical framework for acoustic streaming prediction in mid-air phased arrays

Ancestral motif enables broad DNA binding by NIN, a master regulator of rhizobial symbiosis

Macrophage immune cells need constant reminders to retain memories of prior infections

Ultra-endurance running may accelerate aging and breakdown of red blood cells

Ancient mind-body practice proven to lower blood pressure in clinical trial

SwRI to create advanced Product Lifecycle Management system for the Air Force

Natural selection operates on multiple levels, comprehensive review of scientific studies shows

Developing a national research program on liquid metals for fusion

AI-powered ECG could help guide lifelong heart monitoring for patients with repaired tetralogy of fallot

Global shark bites return to average in 2025, with a smaller proportion in the United States

Millions are unaware of heart risks that don’t start in the heart

What freezing plants in blocks of ice can tell us about the future of Svalbard’s plant communities

A new vascularized tissueoid-on-a-chip model for liver regeneration and transplant rejection

Augmented reality menus may help restaurants attract more customers, improve brand perceptions

[Press-News.org] Toxin from brain cells triggers neuron loss in human ALS modelStudy in human cells may improve ability to identify useful drug targets