(Press-News.org) JUPITER, FL—February 9, 2014—In research that could ultimately lead to many new medicines, scientists from the Florida campus of The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have developed a potentially general approach to design drugs from genome sequence. As a proof of principle, they identified a highly potent compound that causes cancer cells to attack themselves and die.

"This is the first time therapeutic small molecules have been rationally designed from only an RNA sequence—something many doubted could be done," said Matthew Disney, PhD, an associate professor at TSRI who led the study. "In this case, we have shown that that approach allows for specific and unprecedented targeting of an RNA that causes cancer."

The technique, described in the journal Nature Chemical Biology online ahead of print on February 9, 2014, was dubbed Inforna.

"With our program, we can identify compounds with high specificity," said Sai Pradeep Velagapudi, the first author of the study and a graduate student working in the Disney lab. "In the future, we hope we can design drug candidates for other cancers or for any pathological RNA."

In Search of New Approaches

In their research program, Disney and his team has been developing approaches to understand the binding of drugs to RNA folds. In particular, the lab is interested in manipulating microRNAs.

Discovered only in the 1990s, microRNAs are short molecules that work within virtually all animal and plant cells. Typically each one functions as a "dimmer switch" for one or more genes; it binds to the transcripts of those genes and effectively keeps them from being translated into proteins. In this way microRNAs can regulate a wide variety of cellular processes.

Some microRNAs have been associated with diseases. MiR-96 microRNA, for example, is thought to promote cancer by discouraging a process called apoptosis or programmed cell death that can rid the body of cells that begin to grow out of control.

As part of its long-term program, the Disney lab developed computational approaches that can mine information against such genome sequences and all cellular RNAs with the goal of identifying drugs that target such disease-associated RNAs while leaving others unaffected.

"In recent years we've seen an explosion of information about the many roles of RNA in biology and medicine," said Peter Preusch, PhD, of the National Institute of Health's National Institute of General Medical Sciences, which partially funded the research. "This new work is another example of how Dr. Disney is pioneering the use of small molecules to manipulate disease-causing RNAs, which have been underexplored as potential drug targets."

'Unprecedented' Findings

In the new study, Disney and colleagues describe their computational technique, which identifies optimal drug targets by mining a database of drug-RNA sequence ("motif") interactions against thousands of cellular RNA sequences.

Using Inforna, the team identified compounds that can target microRNA-96, as well as additional compounds that target nearly two dozen other disease-associated microRNAs.

The researchers showed that the drug candidate that inhibited microRNA-96 inhibited cancer cell growth. Importantly, they also showed that cells without functioning microRNA-96 were unaffected by the drug.

"This illustrates an unparalleled selectivity for the compound," Disney noted. "In contrast, typical cancer therapeutics target cells indiscriminately, often leading to side effects that can make these drugs difficult for patients to tolerate."

Disney added that the new drug candidate, which is easy to produce and cell permeable, targets microRNA-96 far more specifically than the state-of-the-art method to target RNA (using oligonucleotides) currently in use. "That's unprecedented and provides great excitement for future developments."

INFORMATION:

In addition to Disney and Velagapudi, Steven M. Gallo of the University of Buffalo was an author of the study, "Sequence-Based Design of Bioactive Small Molecules That Target Precursor MicroRNAs."

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant R01GM097455) and the Camille and Henry Dreyfus Foundation.

Scientists invent advanced approach to identify new drug candidates from genome sequence

As proof-of-principle, the team designs potent anti-cancer compound

2014-02-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Fight or flight? Vocal cues help deer decide during mating season

2014-02-10

Previous studies have shown that male fallow deer, known as bucks, can call for a mate more than 3000 times per hour during the rut (peak of the mating season), and their efforts in calling, fighting and mating can leave them sounding hoarse.

In this new study, published today (10 February) in the journal Behavioral Ecology, scientists were able to gauge that fallow bucks listen to the sound quality of rival males' calls and evaluate how exhausted the caller is and whether they should fight or keep their distance.

"Fallow bucks are among the most impressive vocal athletes ...

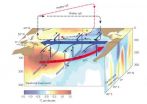

Pacific trade winds stall global surface warming -- for now

2014-02-10

Heat stored in the western Pacific Ocean caused by an unprecedented strengthening of the equatorial trade winds appears to be largely responsible for the hiatus in surface warming observed over the past 13 years.

New research published today in the journal Nature Climate Change indicates that the dramatic acceleration in winds has invigorated the circulation of the Pacific Ocean, causing more heat to be taken out of the atmosphere and transferred into the subsurface ocean, while bringing cooler waters to the surface.

"Scientists have long suspected that extra ocean ...

Seven new genetic regions linked to type 2 diabetes

2014-02-10

Seven new genetic regions associated with type 2 diabetes have been identified in the largest study to date of the genetic basis of the disease.

DNA data was brought together from more than 48,000 patients and 139,000 healthy controls from four different ethnic groups. The research was conducted by an international consortium of investigators from 20 countries on four continents, co-led by investigators from Oxford University's Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics.

The majority of such 'genome-wide association studies' have been done in populations with European ...

Optogenetic toolkit goes multicolor

2014-02-10

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Optogenetics is a technique that allows scientists to control neurons' electrical activity with light by engineering them to express light-sensitive proteins. Within the past decade, it has become a very powerful tool for discovering the functions of different types of cells in the brain.

Most of these light-sensitive proteins, known as opsins, respond to light in the blue-green range. Now, a team led by MIT has discovered an opsin that is sensitive to red light, which allows researchers to independently control the activity of two populations of neurons ...

Clues to cancer pathogenesis found in cell-conditioned media

2014-02-10

Philadelphia, PA, February 10, 2014 – Primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) is a rare B-cell neoplasm distinguished by its tendency to spread along the thin serous membranes that line body cavities without infiltrating or destroying nearby tissue. By growing PEL cells in culture and analyzing the secretome (proteins secreted into cell-conditioned media), investigators have identified proteins that may explain PEL pathogenesis, its peculiar cell adhesion, and migration patterns. They also recognized related oncogenic pathways, thereby providing rationales for more individualized ...

Smoking linked with increased risk of most common type of breast cancer

2014-02-10

Young women who smoke and have been smoking a pack a day for a decade or more have a significantly increased risk of developing the most common type of breast cancer. That is the finding of an analysis published early online in Cancer, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Cancer Society. The study indicates that an increased risk of breast cancer may be another health risk incurred by young women who smoke.

The majority of recent studies evaluating the relationship between smoking and breast cancer risk among young women have found that smoking is linked with an increased ...

No strength in numbers

2014-02-10

Urban legislators have long lamented that they do not get their fair share of bills passed in state governments, often blaming rural and suburban interests for blocking their efforts. Now a new study confirms one of those suspicions but surprisingly refutes the other.

The analysis—of 1,736 bills in 13 states over 120 years—found that big-city legislation was passed at dramatically lower rates than bills for smaller places.

However, rural and suburban colleagues should not be blamed for the dismal track record, conclude co-authors Gerald Gamm of the University of Rochester ...

Virtual avatars may impact real-world behavior

2014-02-10

How you represent yourself in the virtual world of video games may affect how you behave toward others in the real world, according to new research published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

"Our results indicate that just five minutes of role-play in virtual environments as either a hero or villain can easily cause people to reward or punish anonymous strangers," says lead researcher Gunwoo Yoon of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

As Yoon and co-author Patrick Vargas note, virtual environments afford people ...

Huntington disease prevention trial shows creatine safe, suggests slowing of progression

2014-02-08

The first clinical trial of a drug intended to delay the onset of symptoms of Huntington disease (HD) reveals that high-dose treatment with the nutritional supplement creatine was safe and well tolerated by most study participants. In addition, neuroimaging showed a treatment-associated slowing of regional brain atrophy, evidence that creatine might slow the progression of presymptomatic HD. The Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) study also utilized a novel design that allowed participants – all of whom were at genetic risk for the neurodegenerative disorder – to enroll ...

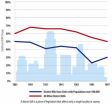

Stroke trigger more deadly for African-Americans

2014-02-08

ANN ARBOR, Mich. — Infection is a stronger trigger of stroke death in African- Americans than in whites, a University of Michigan study shows.

African-Americans were 39 times more likely to die of a stroke if they were exposed to an infection in the previous month when compared to other time periods while whites were four times more likely and Hispanics were five times more likely to die of stroke after an infection, according to the findings that appear online Feb. 7 in Neurology.

The most frequent infections were urinary, skin, and respiratory tract infections ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

GLP-1 drugs associated with reduced need for emergency care for migraine

New knowledge on heritability paves the way for better treatment of people with chronic inflammatory bowel disease

Under the Lens: Microbiologists Nicola Holden and Gil Domingue weigh in on the raw milk debate

Science reveals why you can’t resist a snack – even when you’re full

Kidney cancer study finds belzutifan plus pembrolizumab post-surgery helps patients at high risk for relapse stay cancer-free longer

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

[Press-News.org] Scientists invent advanced approach to identify new drug candidates from genome sequenceAs proof-of-principle, the team designs potent anti-cancer compound