(Press-News.org) As climate change unfolds over the next century, plants and animals will need to adapt or shift locations to follow their ideal climate. A new study provides an innovative global map of where species are likely to succeed or fail in keeping up with a changing climate. The findings appear in the science journal Nature.

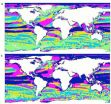

As part of a UC Santa Barbara National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis (NCEAS) working group, 18 international researchers analyzed 50 years of sea surface and land temperature data (1960-2009). They also projected temperature changes under two future scenarios, one that assumes greenhouse gas emissions are stabilized by 2100 and a second that assumes these emissions continue to increase. The resulting maps display where new temperature conditions are being generated and where existing environments may disappear.

This rare global study, which examines scenarios both on land and in the ocean, demonstrates that climate migration is far more complex than a simple shift toward the poles. "As species move to track their ideal temperature conditions, they will sometimes run into what we call a 'climate sink,' where the preferred climate simply disappears leaving species nowhere to go because they are up against a coastline or other barrier," explained Carrie Kappel, an NCEAS associate and one of the paper's authors. "There are a number of those sinks around the world where movement is blocked by a coastline, like in the northern Adriatic Sea or the northern Gulf of Mexico, and there's no way out because it's warmer everywhere behind."

Australia offers a terrestrial example. There, species already experiencing warmer temperatures have started to seek relief by moving to higher elevations, or farther south. However, some species of animals and plants cannot move large distances, and some cannot move at all.

"Species migration can have important consequences for local biodiversity," said corresponding author Elvira Poloczanska, a research scientist with the Climate Adaptation Flagship of Australia's national science agency, the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) in Brisbane. "For example, the dry, flat continental interior of Australia is a hot, arid region where species already exist close to the margin of their thermal tolerances. Some species driven south from monsoonal northern Australia in the hope of cooler habitats may perish in one of the harshest places on Earth."

The maps generated from the study data not only show areas where plants and animals may struggle to find new homes in a changing climate but also provide crucial information for targeting conservation efforts — information that could help conservation planners think more strategically about how best to manage biodiversity for future sustainability.

"One of the greatest challenges these days is how to help species survive in the face of climate change," said co-author Ben Halpern, a professor at UCSB's Bren School of Environmental Science & Management. "The maps we produced offer a key tool for helping guide these decisions. For example, where species are likely to face climate traps, we will need to explore less traditional actions, such as assisted migration, where people help move species past barriers into their preferred environment."

"From other work, we know that many species have shifted where they live in ways that match the pattern of temperature change over the last 60 years," Kappel noted. "This gives us confidence that we can base conservation planning on what we've learned about what's already happening."

According to Halpern, it's not a question of whether climate change is happening, but what we can do about it. "The writing is on the wall: species have already started moving in response to climate change," he said. "We can either sit back and watch as species get squeezed out of existence and food webs reshuffle or we can try to be proactive in designing conservation strategies. Our research and maps offer a window into what the future of biodiversity will look like, and we have a chance to improve the view from that window."

INFORMATION:

Maps show expected redistribution of global species due to climate change

An international team of scientists tracks how fast and in which direction local climates -- and species -- have shifted

2014-02-11

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Obese children more likely to have complex elbow fractures and further complications

2014-02-11

ROSEMONT, Ill.─Pediatric obesity is currently an epidemic, with the prevalence having quadruped over the last 25 years. Children diagnosed with obesity can be at risk for various long-term health issues and may be putting their musculoskeletal system at risk. According to new research in the February issue of the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (JBJS), obese children who sustain a supracondylar humeral (above the elbow) fracture can be expected to have more complex fractures and experience more postoperative complications than children of a normal weight.

"These ...

Giant mass extinction may have been quicker than previously thought

2014-02-11

The largest mass extinction in the history of animal life occurred some 252 million years ago, wiping out more than 96 percent of marine species and 70 percent of life on land — including the largest insects known to have inhabited the Earth. Multiple theories have aimed to explain the cause of what's now known as the end-Permian extinction, including an asteroid impact, massive volcanic eruptions, or a cataclysmic cascade of environmental events. But pinpointing the cause of the extinction requires better measurements of how long the extinction period lasted.

Now researchers ...

High pollutant levels in Guánica Bay 'represent serious toxic threat' to corals

2014-02-11

The pollutants measured in the sediments of Guánica Bay, Puerto Rico, in a new NOAA study were among the highest concentrations of PCBs, chlordane, chromium and nickel ever measured in the history of NOAA's National Status & Trends, a nationwide contaminant monitoring program that began in 1986.

Researchers from the National Ocean Service's National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science (NCCOS) studied the reef's ecology to help establish baseline conditions that coastal managers can use to measure changes resulting from new efforts to manage pollution. Among the items studied ...

Design prototype chip makes possible a fully implantable cochlear implant

2014-02-11

BOSTON (Feb. 10, 2014) — Researchers from Massachusetts Eye and Ear, Harvard Medical School, and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have designed a prototype system-on-chip (SoC) that could make possible a fully implanted cochlear implant. They will present their findings on Feb. 11at the IEEE International Solid State Circuits Conference in San Francisco.

A cochlear implant is a device that electronically stimulates the auditory nerve to restore hearing in people with profound hearing loss. Conventional cochlear implants are made up of an external unit with ...

NASA's TRMM satellite eyes rainfall in Tropical Cyclone Fobane

2014-02-11

Some towering thunderstorms were spotted in Tropical Cyclone Fobane as NASA's TRMM satellite passed over the Southern Indian Ocean on February 10. Fobane was formerly Tropical Cyclone 14S and when it strengthened into a tropical storm it was renamed.

NASA and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency manages the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission satellite known as TRMM. TRMM has the capability to measure rainfall rates from space and data that can be used to determine the heights of thunderstorms that make up a storm. When TRMM passed over Tropical Cyclone Fobane on February ...

Cars, computers, TVs spark obesity in developing countries

2014-02-11

The spread of obesity and type-2 diabetes could become epidemic in low-income countries, as more individuals are able to own higher priced items such as TVs, computers and cars. The findings of an international study, led by Simon Fraser University health sciences professor Scott Lear, are published today in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Lear headed an international research team that analyzed data on more than 150,000 adults from 17 countries, ranging from high and middle income to low-income nations.

Researchers, who questioned participants about ownership ...

Recycling of 'chauffeur protein' helps regulate fat production

2014-02-11

Studying a cycle of protein interactions needed to make fat, Johns Hopkins researchers say they have discovered a biological switch that regulates a protein that causes fatty liver disease in mice. Their findings, they report, may help develop drugs to decrease excessive fat production and its associated conditions in people, including fatty liver disease and diabetes.

A summary of the research appeared online on Jan. 29 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

"We've learned how the body finely tunes levels of a protein called SCAP that is required to turn on fat production ...

Long distance signals protect brain from viral infections

2014-02-11

The brain contains a defense system that prevents at least two unrelated viruses—and possibly many more—from invading the brain at large. The research is published online ahead of print in the Journal of Virology.

"Our work points to the remarkable ability of the immune system, even within the brain, to protect us against opportunistic viruses," says Anthony van den Pol of Yale University, an author on the study.

The research explains a long-standing mystery. The olfactory mucosa in the nose can serve as a conduit for a number of viruses to enter the brain including ...

Mayo Clinic identifies a key cellular pathway in prostate cancer

2014-02-11

ROCHESTER, Minn. — Mayo Clinic researchers have shed light on a new mechanism by which prostate cancer develops in men. Central to development of nearly all prostate cancer cases are malfunctions in the androgen receptor — the cellular component that binds to male hormones. The research team has shown that SPOP, a protein that is most frequently mutated in human prostate cancers, is a key regulator of androgen receptor activity that prevents uncontrolled growth of cells in the prostate and thus helps prevent cancer. The findings appear in the journal Cell Reports.

"By ...

Flowing water on Mars appears likely but hard to prove

2014-02-11

Martian experts have known since 2011 that mysterious, possibly water-related streaks appear and disappear on the planet's surface. Georgia Institute of Technology Ph.D. candidate Lujendra Ojha discovered them while an undergraduate at the University of Arizona. These features were given the descriptive name of recurring slope lineae (RSL) because of their shape, annual reappearance and occurrence generally on steep slopes such as crater walls. Ojha has been taking a closer look at this phenomenon, searching for minerals that RSL might leave in their wake, to try to understand ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Tiny bubbles, big breakthrough: Cracking cancer’s “fortress”

A biological material that becomes stronger when wet could replace plastics

Glacial feast: Seals caught closer to glaciers had fuller stomachs

Get the picture? High-tech, low-cost lens focuses on global consumer markets

Antimicrobial resistance in foodborne bacteria remains a public health concern in Europe

Safer batteries for storing energy at massive scale

How can you rescue a “kidnapped” robot? A new AI system helps the robot regain its sense of location in dynamic, ever-changing environments

Brainwaves of mothers and children synchronize when playing together – even in an acquired language

A holiday to better recovery

Cal Poly’s fifth Climate Solutions Now conference to take place Feb. 23-27

Mask-wearing during COVID-19 linked to reduced air pollution–triggered heart attack risk in Japan

Achieving cross-coupling reactions of fatty amide reduction radicals via iridium-photorelay catalysis and other strategies

Shorter may be sweeter: Study finds 15-second health ads can curb junk food cravings

Family relationships identified in Stone Age graves on Gotland

Effectiveness of exercise to ease osteoarthritis symptoms likely minimal and transient

Cost of copper must rise double to meet basic copper needs

A gel for wounds that won’t heal

Iron, carbon, and the art of toxic cleanup

Organic soil amendments work together to help sandy soils hold water longer, study finds

Hidden carbon in mangrove soils may play a larger role in climate regulation than previously thought

Weight-loss wonder pills prompt scrutiny of key ingredient

Nonprofit leader Diane Dodge to receive 2026 Penn Nursing Renfield Foundation Award for Global Women’s Health

Maternal smoking during pregnancy may be linked to higher blood pressure in children, NIH study finds

New Lund model aims to shorten the path to life-saving cell and gene therapies

Researchers create ultra-stretchable, liquid-repellent materials via laser ablation

Combining AI with OCT shows potential for detecting lipid-rich plaques in coronary arteries

SeaCast revolutionizes Mediterranean Sea forecasting with AI-powered speed and accuracy

JMIR Publications’ JMIR Bioinformatics and Biotechnology invites submissions on Bridging Data, AI, and Innovation to Transform Health

Honey bees navigate more precisely than previously thought

Air pollution may directly contribute to Alzheimer’s disease

[Press-News.org] Maps show expected redistribution of global species due to climate changeAn international team of scientists tracks how fast and in which direction local climates -- and species -- have shifted