(Press-News.org) For four decades, waste from nearby manufacturing plants flowed into the waters of New Bedford Harbor—an 18,000-acre estuary and busy seaport. The harbor, which is contaminated with polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and heavy metals, is one of the EPA's largest Superfund cleanup sites.

It's also the site of an evolutionary puzzle that researchers at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and their colleagues have been working to solve.

Atlantic killifish—common estuarine fishes about three inches long—are not only tolerating the toxic conditions in the harbor, they seem to be thriving there. How have they been able to adapt and live in such a highly contaminated environment?

In a new paper published in BMC Evolutionary Biology, researchers found that changes in a receptor protein, called the aryl hydrocarbon receptor 2 (AHR2), may explain how killifish in New Bedford Harbor evolved genetic resistance to PCBs.

Killifish are prey fish that do not migrate. They live their whole lives in the same area, generally within a few hundred yards of the spot where they were hatched. Unlike fish that may come in and out of the harbor sporadically during the summer months to feed, the killifish are there year round and spend winters burrowing into the contaminated sediment.

Normally when fish are exposed to harmful chemicals, the body steps up production of enzymes that break down the pollutants, a process controlled by the AHR2 protein. Some of the PCBs are not broken down in this way, and their continued stimulation of AHR2 disrupts cellular functions, leading to toxicity. In the New Bedford Harbor killifish, the AHR2 system has become resistant to this effect.

"The killifish have managed to shut down the pathway," said Mark Hahn, a biologist at WHOI and coauthor of the paper. "It's an example of how some populations are able to adapt to changes in their environment—a snapshot of evolution at work."

The research team, which includes colleagues from the Atlantic Ecology Division of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the Boston University School of Public Health, and the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, used a "candidate gene" approach, sequencing the protein-coding portion of three candidate resistance genes (AHR1, AHR2, AHRR) in fish from the New Bedford site and six other locations, both clean and polluted, along the northeast coast.

Looking for single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) or subtle variations in the DNA sequence, they found differences in AHR2, which plays an important role in mediating toxicity in early life stages.

"The function of this receptor is what mediates the toxic effects," said Sibel Karchner, a coauthor and biologist in Hahn's lab. "If you don't have a functional receptor, then you're not going to get the toxic effects as much as a fish that does."

AHR2 in killifish has 951 amino acids and nine of those vary among individuals. The different combinations of amino acid variants lead to 26 different forms of the protein.

"We see that the pattern of variants present in the New Bedford Harbor killifish is much different from the patterns at nearby sites, which is unexpected under normal circumstances," Hahn said. "There are a few protein variants that are common in New Bedford Harbor killifish, but uncommon elsewhere. Similarly, the protein variants that are most common at the nearby reference sites are much less common in the New Bedford Harbor killifish."

A companion paper published in BMC Evolutionary Biology by colleagues at the EPA lab in Narragansett, RI, that used a "candidate gene scan" approach—examining SNPs from 42 genes associated with the AHR pathway—also identified AHR2 as a gene that appears to be under selection and is likely to be involved in the resistance. The results suggest that evolution of resistance in independent populations of killifish converges on the same target gene.

"The results of these studies and the genetic tools developed in the course of these studies are helping to dissect how evolution occurs on a contemporary (rather than geological) scale and why some species are more likely to adapt to a rapidly changing world," said Diane Nacci, a research biologist at EPA and coauthor on both papers.

AHR2 is also the same gene identified in a 2011 Science paper by WHOI biologists and colleagues from New York University and NOAA on PCB-resistant tomcod from the Hudson River. AHR2 proteins in the Hudson River tomcod are missing two of the 1,104 amino acids normally found in this protein.

"Even though the specific molecular changes that are found in PCB-resistant tomcod and killifish are different, in both species AHR2 seems to be one of the genes—possibly the major gene—that is responsible for the resistance," Hahn said.

While the killifish themselves seem to be immune to the toxic effects of the PCBs, they can still transfer contaminants up the food chain. They're a major source of food for bluefish, striped bass and other fish eaten by humans.

Despite their healthy appearance, there could be unknown negative costs for the New Bedford Harbor killifish associated with the resistance to PCBs. Researchers will look next at whether the adaptation affects how the killifish are able to respond to other kinds of stressors in their environment, such as low oxygen levels.

"Obviously, the fact that they are resistant to PCBs allows them to survive in this really polluted environment, but what will happen once the harbor gets cleaned up? There could be costs that make it no longer adaptive for these fish to live there," Hahn said.

"It's a fascinating example of how human activities can drive evolution," he added. "The ability to adapt to changing conditions is going to become even more important as humans impact the environment, whether it's from ocean acidification or increasing temperatures or other types of global changes that are occurring."

INFORMATION:

In addition to Hahn and Karchner, WHOI researchers involved in the work included lead author Adam Reitzel (now an Assistant Professor at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte) and Diana Franks. This work was supported by the National Insitute of Environmental Health Sciences through the Superfund Research Program at Boston University, the Hudson River Foundation, and a National Science Foundation grant.

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution is a private, non-profit organization on Cape Cod, Mass., dedicated to marine research, engineering, and higher education. Established in 1930 on a recommendation from the National Academy of Sciences, its primary mission is to understand the ocean and its interaction with the Earth as a whole, and to communicate a basic understanding of the ocean's role in the changing global environment.

Solving an evolutionary puzzle

New Bedford Harbor pollution prompts PCB-resistance in Atlantic killifish

2014-02-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

NIF experiments show initial gain in fusion fuel

2014-02-13

LIVERMORE, Calif. – Ignition – the process of releasing fusion energy equal to or greater than the amount of energy used to confine the fuel – has long been considered the "holy grail" of inertial confinement fusion science. A key step along the path to ignition is to have "fuel gains" greater than unity, where the energy generated through fusion reactions exceeds the amount of energy deposited into the fusion fuel.

Though ignition remains the ultimate goal, the milestone of achieving fuel gains greater than 1 has been reached for the first time ever on any facility. ...

Well-child visits linked to more than 700,000 subsequent flu-like illnesses

2014-02-13

CHICAGO (February 12, 2014) – New research shows that well-child doctor appointments for annual exams and vaccinations are associated with an increased risk of flu-like illnesses in children and family members within two weeks of the visit. This risk translates to more than 700,000 potentially avoidable illnesses each year, costing more than $490 million annually. The study was published in the March issue of Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, the journal of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America.

"Well child visits are critically important. However, ...

'Viewpoint' addresses IOM report on genome-based therapeutics and companion diagnostics

2014-02-13

The promise of personalized medicine, says University of Vermont (UVM) molecular pathologist Debra Leonard, M.D., Ph.D., is the ability to tailor therapy based on markers in the patient's genome and, in the case of cancer, in the cancer's genome. Making this determination depends on not one, but several genetic tests, but the system guiding the development of those tests is complex, and plagued with challenges.

In a February 12, 2014 Online First Journal of the American Medical Association "Viewpoint" article, Leonard and colleagues address this issue in conjunction ...

Rare bacteria outbreak in cancer clinic tied to lapse in infection control procedure

2014-02-13

CHICAGO (February 12, 2014) – Improper handling of intravenous saline at a West Virginia outpatient oncology clinic was linked with the first reported outbreak of Tsukamurella spp., gram-positive bacteria that rarely cause disease in humans, in a new report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The report was published in the March issue of Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, the journal of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America.

"This outbreak illustrates the need for outpatient clinics to follow proper infection control guidelines ...

No such thing as porn 'addiction,' researchers say

2014-02-13

Journalists and psychologists are quick to describe someone as being a porn "addict," yet there's no strong scientific research that shows such addictions actually exists. Slapping such labels onto the habit of frequently viewing images of a sexual nature only describes it as a form of pathology. These labels ignore the positive benefits it holds. So says David Ley, PhD, a clinical psychologist in practice in Albuquerque, NM, and Executive Director of New Mexico Solutions, a large behavioral health program. Dr. Ley is the author of a review article about the so-called "pornography ...

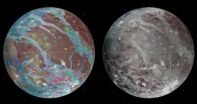

Researchers create first global map of Ganymede

2014-02-13

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Scientists, including Brown University geologists and students, have completed the first global geological map of Ganymede, Jupiter's largest moon and the largest in the solar system.

With its varied terrain and possible underground ocean, Ganymede is considered a prime target in the search for habitable environments in the solar system, and the researchers hope this new map will aid in future exploration. The work, led by Geoffrey Collins, a Ph.D. graduate of Brown now a professor at Wheaton College in Massachusetts, took years to ...

Penn geophysicist teams with mathematicians to describe how river rocks round

2014-02-13

For centuries, geologists have recognized that the rocks that line riverbeds tend to be smaller and rounder further downstream. But these experts have not agreed on the reason these patterns exist. Abrasion causes rocks to grind down and become rounder as they are transported down the river. Does this grinding reduce the size of rocks significantly, or is it that smaller rocks are simply more easily transported downstream?

A new study by the University of Pennsylvania's Douglas Jerolmack, working with mathematicians at Budapest University of Technology and Economics, ...

Happy couples can get a big resolution to a big fight -- mean talk aside

2014-02-13

Being critical, angry and defensive isn't always a bad thing for couples having a big disagreement — provided they are in a satisfying relationship. In that case, they likely will have a "big resolution" regardless of how negative they were during the discussion, according to a study by a Baylor University psychologist.

Until now, there have been two opposing ideas on negative communication in conflict: one is to refrain from using it, while the other suggests doing so is a natural part of productive interaction to resolve conflict. But findings from the latest research ...

Dartmouth study shows US Southwest irrigation system facing decline after 4 centuries

2014-02-13

Communal irrigation systems known as acequias that have sustained farming villages in the arid southwestern United States for centuries are struggling because of dwindling snowmelt runoff and social and economic factors that favor modernism over tradition, a Dartmouth College study finds.

The results reflect similar changes around the world, where once isolated communities are becoming integrated into larger economies, which provide benefits of modern living but also the uncertainties of larger-scale market fluctuations. The study appears in the journal Global Environmental ...

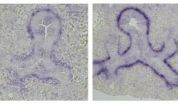

Prenatal vitamin A deficiency tied to postnatal asthma

2014-02-13

NEW YORK, NY (February 12, 2014) — A team of Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) investigators led by Wellington V. Cardoso, MD, PhD, has found the first direct evidence of a link between prenatal vitamin A deficiency and postnatal airway hyperresponsiveness, a hallmark of asthma. The study, conducted in mice, shows that short-term deficit of this essential vitamin while the lung is forming can cause profound changes in the smooth muscle that surrounds the airways, causing the adult lungs to respond to environmental or pharmacological stimuli with excessive narrowing ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Pulsed dynamic water electrolysis: Mass transfer enhancement, microenvironment regulation, and hydrogen production optimization

Coordination thermodynamic control of magnetic domain configuration evolution toward low‑frequency electromagnetic attenuation

High‑density 1D ionic wire arrays for osmotic energy conversion

DAYU3D: A modern code for HTGR thermal-hydraulic design and accident analysis

Accelerating development of new energy system with “substance-energy network” as foundation

Recombinant lipidated receptor-binding domain for mucosal vaccine

Rising CO₂ and warming jointly limit phosphorus availability in rice soils

Shandong Agricultural University researchers redefine green revolution genes to boost wheat yield potential

Phylogenomics Insights: Worldwide phylogeny and integrative taxonomy of Clematis

Noise pollution is affecting birds' reproduction, stress levels and more. The good news is we can fix it.

Researchers identify cleaner ways to burn biomass using new environmental impact metric

Avian malaria widespread across Hawaiʻi bird communities, new UH study finds

New study improves accuracy in tracking ammonia pollution sources

Scientists turn agricultural waste into powerful material that removes excess nutrients from water

Tracking whether California’s criminal courts deliver racial justice

Aerobic exercise may be most effective for relieving depression/anxiety symptoms

School restrictive smartphone policies may save a small amount of money by reducing staff costs

UCLA report reveals a significant global palliative care gap among children

The psychology of self-driving cars: Why the technology doesn’t suit human brains

Scientists discover new DNA-binding proteins from extreme environments that could improve disease diagnosis

Rapid response launched to tackle new yellow rust strains threatening UK wheat

How many times will we fall passionately in love? New Kinsey Institute study offers first-ever answer

Bridging eye disease care with addiction services

Study finds declining perception of safety of COVID-19, flu, and MMR vaccines

The genetics of anxiety: Landmark study highlights risk and resilience

How UCLA scientists helped reimagine a forgotten battery design from Thomas Edison

Dementia Care Aware collaborates with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement to advance age-friendly health systems

Growth of spreading pancreatic cancer fueled by 'under-appreciated' epigenetic changes

Lehigh University professor Israel E. Wachs elected to National Academy of Engineering

Brain stimulation can nudge people to behave less selfishly

[Press-News.org] Solving an evolutionary puzzleNew Bedford Harbor pollution prompts PCB-resistance in Atlantic killifish