(Press-News.org) Recently derived equations that describe development patterns in modern urban areas appear to work equally well to describe ancient cities settled thousands of years ago, according to a new study led by a researcher at the University of Colorado Boulder.

"This study suggests that there is a level at which every human society is actually very similar," said Scott Ortman, assistant professor of anthropology at CU-Boulder and lead author of the study published in the journal PLOS ONE. "This awareness helps break down the barriers between the past and present and allows us to view contemporary cities as lying on a continuum of all human settlements in time and place."

Over the last several years, Ortman's colleagues at the Santa Fe Institute (SFI), including Professor Luis Bettencourt, a co-author of the study, have developed mathematical models that describe how modern cities change as their populations grow. For example, scientists know that as a population increases, its settlement area becomes denser, while infrastructure needs per capita decrease and economic production per capita rises.

Ortman noticed that the variables used in these equations, such as cost of moving around, the size of the settled area, the population, and the benefits of people interacting, did not depend on any particular modern technology.

"I realized that if these models are adequate for explaining what's going on in contemporary cities, they should apply to any settlements in any society," he said. "So if these models are on the right track, they should apply to ancient societies too."

To test his idea, Ortman used data that had been collected in the 1960s about 1,500 settlements in central Mexico that spanned from 1,150 years B.C. through the Aztec period, which ended about 500 years ago. The data included the number of dwellings the archaeologists were able to identify, the total settled area and the density of pottery fragments scattered on the surface. Taken together, these artifacts give an indication of the total population numbers and settlement density of the ancient sites.

"We started analyzing the data in the ways we were thinking about with modern cities, and it showed that the models worked," Ortman said.

The discovery that ancient and modern settlements may develop in similar and predictable ways has implications both for archaeologists and people studying today's urban areas. For example, it's common for archaeologists to assume that population density is constant, no matter how large the settlement area, when estimating the population of ancient cities. The new equations could offer a way for archaeologists to get a more accurate head count, by incorporating the idea that population density tends to grow as total area increases.

In the future, the equations may also guide archaeologists in getting an idea of what they're likely to find within a given settlement based on its size, such as the miles of roads and pathways. The equations could also guide expectations about the number of different activities that took place in a settlement and the division of labor.

"There should be a relationship between the population of settlements and the productivity of labor," Ortman said. "So, for example, we would expect larger social networks to be able to produce more public monuments per capita than smaller settlements."

The findings of the new study may also be useful to studies of modern societies. Because ancient settlements were typically less complex than today's cities, they offer a simple "model system" for testing the equations devised to explain modern cities.

"The archaeological record actually provides surprisingly clear tests of these models, and in some cases it's actually much harder to collect comparable data from contemporary cities," Ortman said.

INFORMATION:

Other co-authors of the study include Andrew Cabaniss of Santa Fe Institute and the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill and Jennie Sturm of the University of New Mexico.

The study is available at http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087902.

Ancient settlements and modern cities follow same rules of development, says CU-Boulder

2014-02-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

America's only Clovis skeleton had its genome mapped

2014-02-13

They lived in America about 13,000 years ago where they hunted mammoth, mastodons and giant bison with big spears. The Clovis people were not the first humans in America, but they represent the first humans with a wide expansion on the North American continent – until the culture mysteriously disappeared only a few hundred years after its origin. Who the Clovis people were and which present day humans they are related to has been discussed intensely and the issue has a key role in the discussion about how the Americas were peopled. Today there exists only one human skeleton ...

New target for psoriasis treatment discovered

2014-02-13

Researchers at King's College London have identified a new gene (PIM1), which could be an effective target for innovative treatments and therapies for the human autoimmune disease, psoriasis.

Psoriasis affects around 2 per cent of people in the UK and causes dry, red lesions on the skin which can become sore or itchy and can have significant impact on the sufferer's quality of life.

It is thought that psoriasis is caused by a problem with the body's immune system in which new skin cells are created too rapidly, causing a build up of flaky patches on the skin's surface. ...

Two parents with Alzheimer's disease? Disease may show up decades early on brain scans

2014-02-13

MINNEAPOLIS – People who are dementia-free but have two parents with Alzheimer's disease may show signs of the disease on brain scans decades before symptoms appear, according to a new study published in the February 12, 2014, online issue of Neurology®, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology.

"Studies show that by the time people come in for a diagnosis, there may be a large amount of irreversible brain damage already present," said study author Lisa Mosconi, PhD, with the New York University School of Medicine in New York. "This is why it is ideal ...

Solving an evolutionary puzzle

2014-02-13

For four decades, waste from nearby manufacturing plants flowed into the waters of New Bedford Harbor—an 18,000-acre estuary and busy seaport. The harbor, which is contaminated with polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and heavy metals, is one of the EPA's largest Superfund cleanup sites.

It's also the site of an evolutionary puzzle that researchers at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and their colleagues have been working to solve.

Atlantic killifish—common estuarine fishes about three inches long—are not only tolerating the toxic conditions in the harbor, they ...

NIF experiments show initial gain in fusion fuel

2014-02-13

LIVERMORE, Calif. – Ignition – the process of releasing fusion energy equal to or greater than the amount of energy used to confine the fuel – has long been considered the "holy grail" of inertial confinement fusion science. A key step along the path to ignition is to have "fuel gains" greater than unity, where the energy generated through fusion reactions exceeds the amount of energy deposited into the fusion fuel.

Though ignition remains the ultimate goal, the milestone of achieving fuel gains greater than 1 has been reached for the first time ever on any facility. ...

Well-child visits linked to more than 700,000 subsequent flu-like illnesses

2014-02-13

CHICAGO (February 12, 2014) – New research shows that well-child doctor appointments for annual exams and vaccinations are associated with an increased risk of flu-like illnesses in children and family members within two weeks of the visit. This risk translates to more than 700,000 potentially avoidable illnesses each year, costing more than $490 million annually. The study was published in the March issue of Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, the journal of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America.

"Well child visits are critically important. However, ...

'Viewpoint' addresses IOM report on genome-based therapeutics and companion diagnostics

2014-02-13

The promise of personalized medicine, says University of Vermont (UVM) molecular pathologist Debra Leonard, M.D., Ph.D., is the ability to tailor therapy based on markers in the patient's genome and, in the case of cancer, in the cancer's genome. Making this determination depends on not one, but several genetic tests, but the system guiding the development of those tests is complex, and plagued with challenges.

In a February 12, 2014 Online First Journal of the American Medical Association "Viewpoint" article, Leonard and colleagues address this issue in conjunction ...

Rare bacteria outbreak in cancer clinic tied to lapse in infection control procedure

2014-02-13

CHICAGO (February 12, 2014) – Improper handling of intravenous saline at a West Virginia outpatient oncology clinic was linked with the first reported outbreak of Tsukamurella spp., gram-positive bacteria that rarely cause disease in humans, in a new report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The report was published in the March issue of Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, the journal of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America.

"This outbreak illustrates the need for outpatient clinics to follow proper infection control guidelines ...

No such thing as porn 'addiction,' researchers say

2014-02-13

Journalists and psychologists are quick to describe someone as being a porn "addict," yet there's no strong scientific research that shows such addictions actually exists. Slapping such labels onto the habit of frequently viewing images of a sexual nature only describes it as a form of pathology. These labels ignore the positive benefits it holds. So says David Ley, PhD, a clinical psychologist in practice in Albuquerque, NM, and Executive Director of New Mexico Solutions, a large behavioral health program. Dr. Ley is the author of a review article about the so-called "pornography ...

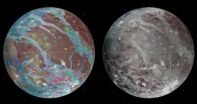

Researchers create first global map of Ganymede

2014-02-13

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Scientists, including Brown University geologists and students, have completed the first global geological map of Ganymede, Jupiter's largest moon and the largest in the solar system.

With its varied terrain and possible underground ocean, Ganymede is considered a prime target in the search for habitable environments in the solar system, and the researchers hope this new map will aid in future exploration. The work, led by Geoffrey Collins, a Ph.D. graduate of Brown now a professor at Wheaton College in Massachusetts, took years to ...