(Press-News.org) UPTON, NY—Armed with just the right atomic arrangements, superconductors allow electricity to flow without loss and radically enhance energy generation, delivery, and storage. Scientists tweak these superconductor recipes by swapping out elements or manipulating the valence electrons in an atom's outermost orbital shell to strike the perfect conductive balance. Most high-temperature superconductors contain atoms with only one orbital impacting performance—but what about mixing those elements with more complex configurations?

Now, researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy's Brookhaven National Laboratory have combined atoms with multiple orbitals and precisely pinned down their electron distributions. Using advanced electron diffraction techniques, the scientists discovered that orbital fluctuations in iron-based compounds induce strongly coupled polarizations that can enhance electron pairing—the essential mechanism behind superconductivity. The study, set to publish soon in the journal Physical Review Letters, provides a breakthrough method for exploring and improving superconductivity in a wide range of new materials.

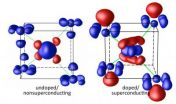

"For the first time, we obtained direct experimental evidence of the subtle changes in electron orbitals by comparing an unaltered, non-superconducting material with its doped, superconducting twin," said Brookhaven Lab physicist and project leader Yimei Zhu.

While the effect of doping the multi-orbital barium iron arsenic—customizing its crucial outer electron count by adding cobalt—mirrors the emergence of high-temperature superconductivity in simpler systems, the mechanism itself may be entirely different.

"Now superconductor theory can incorporate proof of strong coupling between iron and arsenic in these dense electron cloud interactions," said Brookhaven Lab physicist and study coauthor Weiguo Yin. "This unexpected discovery brings together both orbital fluctuation theory and the 50-year-old 'excitonic' theory for high-temperature superconductivity, opening a new frontier for condensed matter physics."

Atomic Jungle Gym

Imagine a child playing inside a jungle gym, weaving through holes in the multicolored metal matrix in much the same way that electricity flows through materials. This particular kid happens to be wearing a powerful magnetic belt that repels the metal bars as she climbs. This causes the jungle gym's grid-like structure to transform into an open tunnel, allowing the child to slide along effortlessly. The real bonus, however, is that this action attracts any nearby belt-wearing children, who can then blaze through that perfect path.

Flowing electricity can have a similar effect on the atomic lattices of superconductors, repelling the negatively charged valence electrons in the surrounding atoms. In the right material, that repulsion actually creates a positively charged pocket, drawing in other electrons as part of the pairing mechanism that enables the loss-free flow of current—the so-called excitonic mechanism. To design an atomic jungle gym that warps just enough to form a channel, scientists audition different combinations of elements and tweak their quantum properties.

"High-temperature copper-oxide superconductors, or cuprates, contain in effect a single orbital and lack the degree of freedom to accommodate strong enough interactions between electricity and the lattice," Yin said. "But the barium iron arsenic we tested has multi-orbital electrons that push and pull the lattice in much more flexible and complex ways, for example by inter-orbital electron redistribution. This feature is especially promising because electricity can shift arsenic's electron cloud much more easily than oxygen's."

In the case of the atomic jungle gym, this complexity demands new theoretical models and experimental data, considering that even a simple lattice made of north-south bar magnets can become a multidimensional dance of attraction and repulsion. To control the doping effects and flow of electricity, scientists needed a window into the orbital interactions.

Tracking Orbits

"Consider measuring waves crashing across the ocean's surface," Zhu said. "We needed to pinpoint those complex fluctuations without having the data obscured by the deep water underneath. The waves represent the all-important electrons in the outer orbital shells, which are barely distinguishable from the layers of inner electrons. For example, each barium atom alone has 56 electrons, but we're only concerned with the two in the outermost layer."

The Brookhaven researchers used a technique called quantitative convergent beam electron diffraction (CBED) to reveal the orbital clouds with subatomic precision. After an electron beam strikes the sample, it bounces off the charged particles to reveal the configuration of the atomic lattice, or the exact arrays of nuclei orbited by electrons. The scientists took thousands of these measurements, subtracted the inner electrons, and converted the data into probabilities—balloon-shaped areas where the valence electrons were most likely to be found.

Shape-Shifting Atoms

The researchers first examined the electron clouds of non-superconducting samples of barium iron arsenic. The CBED data revealed that the arsenic atoms—placed above and below the iron in a sandwich-like shape (see image)—exhibited little shift or polarization of valence electrons. However, when the scientists transformed the compound into a superconductor by doping it with cobalt, the electron distribution radically changed.

"Cobalt doping pushed the orbital electrons in the arsenic outward, concentrating the negative charge on the outside of the 'sandwich' and creating a positively charged pocket closer to the central layer of iron," Zhu said. "We created very precise electronic and atomic displacement that might actually drive the critical temperature of these superconductors higher."

Added Yin, "What's really exciting is that this electron polarization exhibits strong coupling. The quadrupole polarization of the iron, which indicates the orbital fluctuation, couples intimately with the arsenic dipole polarization—this mechanism may be key to the emergence of high-temperature superconductivity in these iron-based compounds. And our results may guide the design of new materials."

This study explored the orbital fluctuations at room temperature under static conditions, but future experiments will apply dynamic diffraction methods to super-cold samples and explore alternative material compositions.

INFORMATION:

The experimental work at Brookhaven Lab was supported by DOE's Office of Science. The materials synthesis was carried out at the Chinese Academy of Sciences' Institute of Physics. Brookhaven Lab coauthors of the study also include Chao Ma, Lijun Wu, and Chris Homes.

DOE's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit the Office of Science website at science.energy.gov.

One of ten national laboratories overseen and primarily funded by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Brookhaven National Laboratory conducts research in the physical, biomedical, and environmental sciences, as well as in energy technologies and national security. Brookhaven Lab also builds and operates major scientific facilities available to university, industry and government researchers. Brookhaven is operated and managed for DOE's Office of Science by Brookhaven Science Associates, a limited-liability company founded by the Research Foundation for the State University of New York on behalf of Stony Brook University, the largest academic user of Laboratory facilities, and Battelle, a nonprofit, applied science and technology organization.

Visit Brookhaven Lab's electronic newsroom for links, news archives, graphics, and more at http://www.bnl.gov/newsroom. Follow Brookhaven Lab on Twitter, http://twitter.com/BrookhavenLab, and find us on Facebook, http://www.facebook.com/BrookhavenLab/.

Superconductivity in orbit: Scientists find new path to loss-free electricity

Brookhaven Lab researchers captured the distribution of multiple orbital electrons to help explain the emergence of superconductivity in iron-based materials

2014-02-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Rewriting the text books: Scientists crack open 'black box' of development

2014-02-14

We know much about how embryos develop, but one key stage – implantation – has remained a

mystery. Now, scientists from Cambridge have discovered a way to study and film this 'black box'

of development. Their results – which will lead to the rewriting of biology text books worldwide

– are published in the journal Cell. Embryo development in mammals occurs in two phases.

During the first phase, pre-implantation, the embryo is a small, free-floating ball of cells

called a blastocyst. In the second, post-implantation, phase the blastocyst embeds itself in the

mother's ...

A role of glucose tolerance could make the adaptor protein p66Shc a new target for cancer and diabetes

2014-02-14

[TORONTO,Canada, Feb 18, 2014] – A protein that has been known until recently as part of a complex communications network within the cell also plays a direct role in regulating sugar metabolism, according to a new study published on-line in the journal Science Signaling (February 18, 2014).

Cell growth and metabolism are tightly controlled processes in our cells. When these functions are disturbed, diseases such as cancer and diabetes occur. Mohamed Soliman, a PhD candidate at the Lunenfeld Tanenbaum Research Institute at Mount Sinai Hospital, found a unique role for ...

IBEX research shows influence of galactic magnetic field extends beyond our solar system

2014-02-14

In a report published today, new research suggests the enigmatic "ribbon" of energetic

particles discovered at the edge of our solar system by NASA's Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX)

may be only a small sign of the vast influence of the galactic magnetic field.

IBEX researchers have sought answers about the ribbon since its discovery in 2009. Comprising

primarily space physicists, the IBEX team realized that the galactic magnetic field wrapped around

our heliosphere — the giant "bubble" that envelops and protects our solar system — appears to

determine the orientation ...

Rebuilding the brain after stroke

2014-02-14

DETROIT – Enhancing the brain's inherent ability to rebuild itself after a stroke with molecular

components of stem cells holds enormous promise for treating the leading cause of long-term

disability in adults.

Michael Chopp, Ph.D., Scientific Director of the Henry Ford Neuroscience Institute, will present

this approach to treating neurological diseases Thursday, Feb. 13, at the American Heart

Association's International Stroke Conference in San Diego.

Although most stroke victims recover some ability to voluntarily use their hands and other body

parts, half are ...

Amidst bitter cold and rising energy costs, new concerns about energy insecurity

2014-02-14

February 13,2014 --With many regions of the country braced by an unrelenting cold snap, the problem of energy insecurity continues to go unreported despite its toll on the most vulnerable. In a new brief, researchers at Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health paint a picture of the families most impacted by this problem and suggest recommendations to alleviate its chokehold on millions of struggling Americans. The authors note that government programs to address energy insecurity are coming up short, despite rising energy costs.

Energy Insecurity (EI) is ...

Harvard scientists find cell fate switch that decides liver, or pancreas?

2014-02-14

Harvard stem cell scientists have a new theory for how stem cells decide whether to become

liver or pancreatic cells during development. A cell's fate, the researchers found, is determined by

the nearby presence of prostaglandin E2, a messenger molecule best known for its role in

inflammation and pain. The discovery, published in the journal Developmental Cell, could potentially

make liver and pancreas cells easier to generate both in the lab and for future cell therapies.

Wolfram Goessling, MD, PhD, and Trista North, PhD, both principal faculty members of the

Harvard ...

Arctic biodiversity under serious threat from climate change according to new report

2014-02-14

Unique and irreplaceable Arctic wildlife and landscapes are crucially at risk due to global warming caused by human activities according to the Arctic Biodiversity Assessment (ABA), a new report prepared by 253 scientists from 15 countries under the auspices of the Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF), the biodiversity working group of the Arctic Council.

"An entire bio-climatic zone, the high Arctic, may disappear. Polar bears and the other highly adapted organisms cannot move further north, so they may go extinct. We risk losing several species forever," says ...

Pregabalin effectively treats restless leg syndrome with less risk of worsening symptoms

2014-02-13

A report in the Feb. 13 New England Journal of Medicine confirms previous studies suggesting that long-term treatment with the type of drugs commonly prescribed to treat restless leg syndrome (RLS) can cause a serious worsening of the condition in some patients. The year-long study from a multi-institutional research team found that pregabalin – which is FDA-approved to treat nerve pain, seizures, and other conditions – was effective in reducing RLS symptoms and was much less likely to cause symptom worsening than pramipexole, one of several drugs that activate the dopamine ...

Environment change threatens indigenous know-how

2014-02-13

The way indigenous cultures around the globe use

traditional medicines and pass on knowledge developed over centuries is directly linked to the

natural environment, new research has found. This makes indigenous cultures susceptible to

environmental change, a threat that comes on top of the challenges posed by globalisation.

"Traditional medicine provides health care for more than half the world's population, with 80 per

cent of people in developing countries relying on these practices to maintain their livelihood. It

is a very important part of traditional knowledge," ...

Understanding the basic biology of bipolar disorder

2014-02-13

Scientists know there is a strong genetic component to bipolar disorder, but they have had an

extremely difficult time identifying the genes that cause it. So, in an effort to better

understand the illness's genetic causes, researchers at UCLA tried a new approach.

Instead of only using a standard clinical interview to determine whether individuals met the

criteria for a clinical diagnosis of bipolar disorder, the researchers combined the results from

brain imaging, cognitive testing, and an array of temperament and behavior measures. Using the

new method, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Genotype-specific response to 144-week entecavir therapy for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B with a particular focus on histological improvement

‘Stiff’ cells provide new explanation for differing symptoms in sickle cell patients

New record of Great White Shark in Spain sparks a 160-year review

Prevalence of youth overweight, obesity, and severe obesity

GLP-1 receptor agonists plus progestins and endometrial cancer risk in nonmalignant uterine diseases

Rejuvenating neurons restores learning and memory in mice

Endocrine Society announces inaugural Rare Endocrine Disease Fellows Program

Sensorimotor integration by targeted priming in muscles with electromyography-driven electro-vibro-feedback in robot-assisted wrist/hand rehabilitation after stroke

New dual-action compound reduces pancreatic cancer cell growth

Wastewater reveals increase in new synthetic opioids during major New Orleans events

Do cash transfers lead to traumatic injury or death?

Eva Vailionis, MS, CGC is presented the 2026 ACMG Foundation Genetic Counselor Best Abstract Award by The ACMG Foundation

Where did that raindrop come from? Tracing the movement of water molecules using isotopes

Planting tree belts on wet farmland comes with an overlooked trade-off

Continuous lower limb biomechanics prediction via prior-informed lightweight marker-GMformer

Researchers discover genetic link to Barrett’s esophagus offering new hope for esophageal cancer patients

Endocrine Society announces inaugural Rare Endocrine Disease Fellows Series

New AI model improves accuracy of food contamination detection

Egalitarianism among hunter-gatherers

AI-Powered R&D Acceleration: Insilico Medicine and CMS announce multiple collaborations in central nervous system and autoimmune diseases

AI-generated arguments are persuasive, even when labeled

New study reveals floods are the biggest drivers of plastic pollution in rivers

Novel framework for real-time bedside heart rate variability analysis

Dogs and cats help spread an invasive flatworm species

Long COVID linked to Alzheimer’s disease mechanisms

Study reveals how chills develop and support the body's defense against infection

Half of the world’s coral reefs suffered major bleaching during the 2014–2017 global heatwave

AI stethoscope can help spot ‘silent epidemic’ of heart valve disease earlier than GPs, study suggests

Researchers rebuild microscopic circadian clock that can control genes

Controlled “oxidative spark”: a surprising ally in brain repair

[Press-News.org] Superconductivity in orbit: Scientists find new path to loss-free electricityBrookhaven Lab researchers captured the distribution of multiple orbital electrons to help explain the emergence of superconductivity in iron-based materials