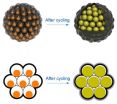

(Press-News.org) An electrode designed like a pomegranate – with silicon nanoparticles clustered like seeds in a tough carbon rind – overcomes several remaining obstacles to using silicon for a new generation of lithium-ion batteries, say its inventors at Stanford University and the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

"While a couple of challenges remain, this design brings us closer to using silicon anodes in smaller, lighter and more powerful batteries for products like cell phones, tablets and electric cars," said Yi Cui, an associate professor at Stanford and SLAC who led the research, reported today in Nature Nanotechnology.

"Experiments showed our pomegranate-inspired anode operates at 97 percent capacity even after 1,000 cycles of charging and discharging, which puts it well within the desired range for commercial operation."

The anode, or negative electrode, is where energy is stored when a battery charges. Silicon anodes could store 10 times more charge than the graphite anodes in today's rechargeable lithium-ion batteries, but they also have major drawbacks: The brittle silicon swells and falls apart during battery charging, and it reacts with the battery's electrolyte to form gunk that coats the anode and degrades its performance.

Over the past eight years, Cui's team has tackled the breakage problem by using silicon nanowires or nanoparticles that are too small to break into even smaller bits and encasing the nanoparticles in carbon "yolk shells" that give them room to swell and shrink during charging.

The new study builds on that work. Graduate student Nian Liu and postdoctoral researcher Zhenda Lu used a microemulsion technique common in the oil, paint and cosmetic industries to gather silicon yolk shells into clusters, and coated each cluster with a second, thicker layer of carbon. These carbon rinds hold the pomegranate clusters together and provide a sturdy highway for electrical currents.

And since each pomegranate cluster has just one-tenth the surface area of the individual particles inside it, a much smaller area is exposed to the electrolyte, thereby reducing the amount of gunk that forms to a manageable level.

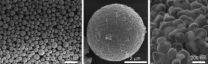

Although the clusters are too small to see individually, together they form a fine black powder that can be used to coat a piece of foil and form an anode. Lab tests showed that pomegranate anodes worked well when made in the thickness required for commercial battery performance.

While these experiments show the technique works, Cui said, the team will have to solve two more problems to make it viable on a commercial scale: They need to simplify the process and find a cheaper source of silicon nanoparticles. One possible source is rice husks: They're unfit for human food, produced by the millions of tons and 20 percent silicon dioxide by weight. According to Liu, they could be transformed into pure silicon nanoparticles relatively easily, as his team recently described in Scientific Reports.

"To me it's very exciting to see how much progress we've made in the last seven or eight years," Cui said, "and how we have solved the problems one by one."

INFORMATION:

The research team also included Jie Zhao, Matthew T. McDowell, Hyun-Wook Lee and Wenting Zhao of Stanford. Cui is a member of the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences, a joint SLAC/Stanford institute. The research was funded by the DOE Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy through the Batteries for Advanced Transportation Technologies program.

Citation: N. Liu, Z. Lu et al., Nature Nanotechnology, 16 February 2014 (10.1038/nnano.2014.6)

New 'pomegranate-inspired' design solves problems for lithium-ion batteries

2014-02-17

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Worldwide study finds that fertilizer destabilizes grasslands

2014-02-17

Lincoln, Neb., Feb. 17, 2014 -- Fertilizer could be too much of a good thing for the world's grasslands, according to study findings to be published online Feb. 16 by the journal Nature.

The worldwide study shows that, on average, additional nitrogen will increase the amount of grass that can be grown. But a smaller number of species thrive, crowding out others that are better adapted to survive in harsher times. It results in wilder swings in the amount of available forage.

"More nitrogen means more production, but it's less stable," said Johannes M.H. Knops, a University ...

Study on flu evolution may change textbooks, history books

2014-02-17

A new study reconstructing the evolutionary tree of flu viruses challenges conventional wisdom and solves some of the mysteries surrounding flu outbreaks of historical significance.

The study, published in the journal Nature, provides the most comprehensive analysis to date of the evolutionary relationships of influenza virus across different host species over time. In addition to dissecting how the virus evolves at different rates in different host species, the study challenges several tenets of conventional wisdom, for example the notion that the virus moves largely ...

CU-Boulder stem cell research may point to new ways of mitigating muscle loss

2014-02-17

New findings on why skeletal muscle stem cells stop dividing and renewing muscle mass during aging points up a unique therapeutic opportunity for managing muscle-wasting conditions in humans, says a new University of Colorado Boulder study.

According to CU-Boulder Professor Bradley Olwin, the loss of skeletal muscle mass and function as we age can lead to sarcopenia, a debilitating muscle-wasting condition that generally hits the elderly hardest. The new study indicates that altering two particular cell-signaling pathways independently in aged mice enhances muscle stem ...

Years after bullying, negative impact on a child's health may remain

2014-02-17

BOSTON (Feb. 17, 2014) —The longer the period of time a child is bullied, the more severe and lasting the impact on a child's health, according to a new study from Boston Children's Hospital published online Feb. 17 in Pediatrics. The study is the first to examine the compounding effects of bullying from elementary school to high school.

"Our research shows that long-term bullying has a severe impact on a child's overall health, and that its negative effects can accumulate and get worse with time," says the study's first author Laura Bogart, PhD, from Boston Children's ...

Why does the brain remember dreams?

2014-02-17

This news release is available in French. Some people recall a dream every morning, whereas others rarely recall one. A team led by Perrine Ruby, an Inserm Research Fellow at the Lyon Neuroscience Research Center (Inserm/CNRS/Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1), has studied the brain activity of these two types of dreamers in order to understand the differences between them. In a study published in the journal Neuropsychopharmacology, the researchers show that the temporo-parietal junction, an information-processing hub in the brain, is more active in high dream recallers. ...

Transfer of knowledge learned seen as a key to improving science education

2014-02-16

CHICAGO -- (Feb. 16, 2014) -- Attendees of a workshop at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science will be immersed into "active learning," an approach inspired by national reports targeting U.S. science education, in general, and, more specifically, the 60 percent dropout rate of students in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM).

"The goal of this session is to take many ideas around improving science education that are out there and make them applicable to the classroom," says Eleanor "Elly" V.H. Vandegrift, associate ...

Using crowdsourcing to solve complex problems

2014-02-16

If two minds are better than one, what could thousands of minds accomplish? The possibilities are endless -- if researchers can learn to effectively harness and utilize all that knowledge.

Northwestern University professor Haoqi Zhang designs new forms of crowd-supported, mixed-initiative systems that tightly integrate crowd work, community process and intelligent user interfaces to solve complex problems that no machine nor person could solve alone. Zhang's systems can ease challenges in designing a custom trip or planning an academic conference, for example.

Zhang ...

What is known about the pathway to aging well?

2014-02-16

CHICAGO --- Daniel K. Mroczek, professor of psychology and professor of medical social sciences in the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences at Northwestern University, will discuss his research at a symposium on resilient aging during the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) annual meeting in Chicago.

The interdisciplinary symposium "The Science of Resilient Aging" will be held from 1:30 to 4:30 p.m., Sunday, Feb. 16, in Grand Ballroom A in the Hyatt Regency Chicago.

Through his research, Mroczek has found that personality traits have emerged ...

Thinking it through: Scientists seek to unlock mysteries of the brain

2014-02-16

Chicago, Illinois - Understanding the human brain is one of the greatest challenges facing 21st century science. If we can rise to this challenge, we will gain profound insights into what makes us human, develop new treatments for brain diseases, and build revolutionary new computing technologies that will have far reaching effects, not only in neuroscience.

Scientists at the European Human Brain Project—set to announce more than a dozen new research partnerships worth Eur 8.3 million in funding later this month—the Allen Institute for Brain Science, and the US BRAIN ...

Loneliness is a major health risk for older adults

2014-02-16

Feeling extreme loneliness can increase an older

person's chances of premature death by 14 percent, according to research by John Cacioppo,

professor of psychology at the University of Chicago.

Cacioppo and his colleagues' work

shows that the impact of loneliness on premature death is nearly as strong as the impact of

disadvantaged socioeconomic status, which they found increases the chances of dying early by 19

percent. A 2010 meta-analysis showed that loneliness has twice the impact on early death as does

obesity, he said.

Cacioppo, the Tiffany ...