(Press-News.org) Imagine someone spent months researching new cities to call home using low-resolution images of unidentified skylines. The pictures were taken from several miles away with a camera intended for portraits, and at sunset. From these fuzzy snapshots, that person claims to know the city's air quality, the appearance of its buildings, and how often it rains.

This technique is similar to how scientists often characterize the atmosphere — including the presence of water and oxygen — of planets outside of Earth's solar system, known as exoplanets, according to a review of exoplanet research published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. A planet's atmosphere is the gateway to its identity, including how it was formed, how it developed and whether it can sustain life, stated Adam Burrows, author of the review and a Princeton University professor of astrophysical sciences. But the dominant methods for studying exoplanet atmospheres are not intended for objects as distant, dim and complex as planets trillions of miles from Earth, Burrows said. They were instead designed to study much closer or brighter objects, such as planets in Earth's solar system and stars.

Nonetheless, scientific reports and the popular media brim with excited depictions of Earth-like planets ripe for hosting life and other conclusions that are based on vague and incomplete data, Burrows wrote in the first in a planned series of essays that examine the current and future study of exoplanets. Despite many trumpeted results, few "hard facts" about exoplanet atmospheres have been collected since the first planet was detected in 1992, and most of these data are of "marginal utility."

The good news is that the past 20 years of study have brought a new generation of exoplanet researchers to the fore that is establishing new techniques, technologies and theories. As with any relatively new field of study, fully understanding exoplanets will require a lot of time, resources and patience, Burrows said.

"Exoplanet research is in a period of productive fermentation that implies we're doing something new that will indeed mature," Burrows said. "Our observations just aren't yet of a quality that is good enough to draw the conclusions we want to draw.

"There's a lot of hype in this subject, a lot of irrational exuberance. Popular media have characterized our understanding as better than it actually is," he said. "They've been able to generate excitement that creates a positive connection between the astrophysics community and the public at large, but it's important not to hype conclusions too much at this point."

The majority of data on exoplanet atmospheres come from low-resolution photometry, which captures the variation in light and radiation an object emits, Burrows reported. That information is used to determine a planet's orbit and radius, but its clouds, surface, and rotation, among other factors, can easily skew the results. Even newer techniques such as capturing planetary transits — which is when a planet passes in front of its star, and was lauded by Burrows as an unforeseen "game changer" when it comes to discovering new planets — can be thrown off by a thick atmosphere and rocky planet core.

All this means that reliable information about a planet can be scarce, so scientists attempt to wring ambitious details out of a few data points. "We have a few hard-won numbers and not the hundreds of numbers that we need," Burrows said. "We have in our minds that exoplanets are very complex because this is what we know about the planets in our solar system, but the data are not enough to constrain even a fraction of these conceptions."

Burrows emphasizes that astronomers need to acknowledge that they will never achieve a comprehensive understanding of exoplanets through the direct-observation, stationary methods inherited from the exploration of Earth's neighbors. He suggests that exoplanet researchers should acknowledge photometric interpretations as inherently flawed and ambiguous. Instead, the future of exoplanet study should focus on the more difficult but comprehensive method of spectrometry, wherein the physical properties of objects are gauged by the interaction of its surface and elemental features with light wavelengths, or spectra. Spectrometry has been used to determine the age and expansion of the universe.

Existing telescopes and satellites are likewise vestiges of pre-exoplanet observation. Burrows calls for a mix of small, medium and large initiatives that will allow the time and flexibility scientists need to develop tools to detect and analyze exoplanet spectra. He sees this as a challenge in a research environment that often puts quick-payback results over deliberate research and observation. Once scientists obtain high-quality spectral data, however, Burrows predicts, "many conclusions reached recently about exoplanet atmospheres will be overturned."

"The way we study planets out of the solar system has to be radically different because we can't 'go' to those planets with satellites or probes," Burrows said. "It's much more an observational science. We have to be detectives. We're trying to find clues and the best clues since the mid-19th century have been in spectra. It's the only means of understanding the atmosphere of these planets."

A longtime exoplanet researcher, Burrows predicted the existence of "hot-Jupiter" planets — gas planets similar to Jupiter but orbiting very close to the parent star — in a paper in the journal Nature months before the first such planet, 51 Pegasi b, was discovered in 1995.

INFORMATION:

Citation: Burrows, Adam S. 2014. Spectra as windows into exoplanet atmospheres. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1304208111

Rife with hype, exoplanet study needs patience and refinement

2014-02-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Frequent flyers, bottle gourds crossed the ocean many times

2014-02-18

Bottle gourds traveled the Atlantic Ocean from Africa and were likely domesticated many times in various parts of the New World, according to a team of scientists who studied bottle gourd genetics to show they have an African, not Asian ancestry.

"Beginning in the 1950s we thought that bottle gourds floated across the ocean from Africa," said Logan Kistler, post-doctoral researcher in anthropology, Penn State. "However, a 2005 genetic study of gourds suggested an Asian origin."

Domesticated bottle gourds are ubiquitous around the world in tropical and temperate areas ...

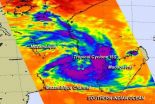

NASA sees Tropical Cyclone 15S form in the Mozambique Channel

2014-02-18

NASA's Aqua satellite passed over Tropical Cyclone 15S as it formed in the Mozambique Channel on Feb. 18 and the AIRS instrument aboard gathered infrared data on its cloud top temperatures and potential.

NASA's Aqua satellite passed over Tropical cyclone 15S on Feb. 18 at 10:53 a.m. EST. The Atmospheric Infrared Sounder or AIRS instrument captured infrared data on the tropical system that showed the highest cloud tops and strongest thunderstorms were in a band that stretched from the east to the south of the center. Cloud top temperatures were near -63F/-52C, indicating ...

Agricultural productivity loss as a result of soil and crop damage from flooding

2014-02-18

URBANA, Ill. – The Cache River Basin, which once drained more than 614,100 acres across six southern Illinois counties, has changed substantively since the ancient Ohio River receded. The basin contains a slow-moving, meandering river; fertile soils and productive farmlands; deep sand and gravel deposits; sloughs and uplands; and one of the most unique and diverse natural habitats in Illinois and the nation.

According to a recent University of Illinois study, the region's agricultural lands dodged a bullet due to the timing of the great flood of April 2011 when the Ohio ...

GW spirituality and health pioneer publishes paper on development of the field

2014-02-18

WASHINGTON (Feb. 18, 2014) — While spirituality played a significant role in health care for centuries, technological advances in the 20th century overshadowed this more human side of medicine. Christina Puchalski, M.D.'94, RESD'97, founder and director of the George Washington University (GW) Institute for Spirituality and Health and professor of medicine at the GW School of Medicine and Health Sciences (SMHS), and co-authors published a commentary in Academic Medicine on the history of spirituality and health, the movement to reclaim medicine's spiritual roots, and the ...

Neuropsychological assessment more efficient than MRI for tracking disease progression

2014-02-18

Amsterdam, NL, February 18, 2014 – Investigators at the University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands, have shown that progression of disease in memory clinic patients can be tracked efficiently with 45 minutes of neuropsychological testing. MRI measures of brain atrophy were shown to be less reliable to pick up changes in the same patients.

This finding has important implications for the design of clinical trials of new anti-Alzheimer drugs. If neuropsychological assessment is used as the outcome measure or "gold standard," fewer patients would be needed to conduct such ...

Artificial cells and salad dressing

2014-02-18

RIVERSIDE, Calif. (http://www.ucr.edu) — A University of California, Riverside assistant professor of engineering is among a group of researchers that have made important discoveries regarding the behavior of a synthetic molecular oscillator, which could serve as a timekeeping device to control artificial cells.

Elisa Franco, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at UC Riverside's Bourns College of Engineering, and the other researchers developed methods to screen thousands of copies of this oscillator using small droplets. They found, surprisingly, that the ...

CASL, Westinghouse simulate neutron behavior in AP1000 reactor core

2014-02-18

OAK RIDGE, Tenn., Feb. 18, 2014 — Scientists and engineers developing more accurate approaches to analyzing nuclear power reactors have successfully tested a new suite of computer codes that closely model "neutronics" — the behavior of neutrons in a reactor core.

Technical staff at Westinghouse Electric Company, LLC, supported by the research team at the Consortium for Advanced Simulation of Light Water Reactors (CASL), used the Virtual Environment for Reactor Applications core simulator (VERA-CS) to analyze its AP1000 advanced pressurized water reactor (PWR). The testing ...

SDSC/UC San Diego researchers hone in on Alzheimer's disease

2014-02-18

Researchers studying peptides using the Gordon supercomputer at the San Diego Supercomputer Center (SDSC) at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) have found new ways to elucidate the creation of the toxic oligomers associated with Alzheimer's disease.

Igor Tsigelny, a research scientist with SDSC, the UCSD Moores Cancer Center, and the Department of Neurosciences, focused on the small peptide called amyloid-beta, which pairs up with itself to form dimers and oligomers.

The scientists surveyed all the possible ways to look at the dynamics of conformational ...

Artificial leaf jumps developmental hurdle

2014-02-18

In a recent early online edition of Nature Chemistry, ASU scientists, along with colleagues at Argonne National Laboratory, have reported advances toward perfecting a functional artificial leaf.

Designing an artificial leaf that uses solar energy to convert water cheaply and efficiently into hydrogen and oxygen is one of the goals of BISfuel – the Energy Frontier Research Center, funded by the Department of Energy, in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry at Arizona State University.

Hydrogen is an important fuel in itself and serves as an indispensible ...

Wistar scientists develop gene test to accurately classify brain tumors

2014-02-18

cientists at The Wistar Institute have developed a mathematical method for classifying forms of glioblastoma, an aggressive and deadly type of brain cancer, through variations in the way these tumor cells "read" genes. Their system was capable of predicting the subclasses of glioblastoma tumors with 92 percent accuracy. With further testing, this system could enable physicians to accurately predict which forms of therapy would benefit their patients the most.

Their research was performed in collaboration with Donald M. O'Rourke, M.D., a neurosurgeon at the University ...