(Press-News.org) Babies who develop leukemia during the first year of life appear to inherit an unfortunate combination of genetic variations that can make the infants highly susceptible to the disease, according to a new study at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and the University of Minnesota.

The research is available online in the journal Leukemia.

Doctors have long puzzled over why it is that babies just a few months old sometimes develop cancer. As infants, they have not lived long enough to accumulate a critical number of cancer-causing mutations.

"Parents always ask why their child has developed leukemia, and unfortunately we have had few answers," said senior author Todd Druley, MD, PhD, a Washington University pediatric oncologist who treats patients at St. Louis Children's Hospital. "Our study suggests that babies with leukemia inherit a strong genetic predisposition to the disease."

The babies appear to have inherited rare genetic variants from both parents that by themselves would not cause problems, but in combination put the infants at high risk of leukemia. These variants most often occurred in genes known to be linked to leukemia in children, said Druley, an assistant professor of pediatrics.

Leukemia occurs rarely in infants, with only about 160 cases diagnosed annually in the United States. But unlike leukemia in children, which most often can be cured, about half of infants who develop leukemia die of the disease.

The researchers sequenced all the genes in the DNA of healthy cells from 23 infants with leukemia and their mothers. Looking at genes in the healthy cells helped the researchers understand which genetic variations were passed from a mother to her child, and by process of elimination, the scientists could determine the father's contribution to a baby's DNA.

Among the families studied, there was no history of pediatric cancers. The scientists also sequenced the DNA of 25 healthy children as a comparison.

"We sequenced every single gene and found that infants with leukemia were born with an excess of damaging changes in genes known to be linked to leukemia," Druley said. "For each child, both parents carried a few harmful genetic variations in their DNA, and just by chance their child inherited all of these changes."

Other children in the families typically don't develop leukemia because a roll of the genetic dice likely means they did not inherit the same combination of harmful genetic changes, he added.

Druley said it's unlikely that the inherited variations alone cause cancer to develop in infants. Rather, the babies likely only needed to accumulate very few additional genetic errors in cells of the bone marrow, where leukemia originates, to develop the cancer in such a short time span.

He and his colleagues now want to study the inherited variations in more detail to understand how they contribute to the development of leukemia. Eventually, with additional research, it may be possible to use a technique called genetic editing to "cut" the harmful gene from the DNA of infants who are susceptible to leukemia and replace it with a healthy version of the same gene, thereby sparing babies and their families from a devastating diagnosis.

Druley, along with his Washington University colleagues in genetics and oncology, also have established the region's first Pediatric Cancer Predisposition Clinic, located at St. Louis Children's Hospital. The team closely follows children with an increased risk of cancer to increase the likelihood that cancers are detected and treated early.

Physical and occupational therapists, audiologists and other health professionals also are available to provide support services to the children. Genetic research conducted through the clinic is designed to improve the surveillance of pediatric cancers and understanding of how and why they develop.

INFORMATION:

The research is funded by the Children's Discovery Institute at Washington University School of Medicine and St. Louis Children's Hospital, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Alex's Lemonade Stand "A" Award, the Hyundai Hope Award, the Eli Seth Matthews Leukemia Foundation and the Children Cancer Research Fund.

Valentine MC, Linaberry AM, Chasnoff S, Hughes AEO, Mallaney C, Sanchez N, Giacalone J, Heerema NA, Hilden JM, Spector LG, Ross JA and Druley TE. Excess congenital non-synonymous variation in leukemia-associated genes in MLL-infant leukemia: a children's oncology group report. Leukemia. Advance online publication, Jan. 10, 2014.

Washington University School of Medicine's 2,100 employed and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient care institutions in the nation, currently ranked sixth in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.

Infants with leukemia inherit susceptibility

2014-02-19

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

NASA satellite sees a ragged eye develop in Tropical Cyclone Guito

2014-02-19

NASA satellite data was an "eye opener" when it came to Tropical Cyclone 15S, now known as Guito in the Mozambique Channel today, Feb. 19, 2014. NASA's Aqua satellite passed over Guito and visible imagery revealed a ragged eye had developed as the tropical cyclone intensified.

The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer or MODIS instrument aboard NASA's Aqua satellite captured a visible image of Tropical Cyclone Guito on Feb. 19 at 1140 UTC/6:40 a.m. EST as it continued moving south through the Mozambique Channel. The image revealed a ragged-looking eye with a band ...

Surveys find that despite economic challenges Malagasy fishers support fishing regulations

2014-02-19

Scientists from the Wildlife Conservation Society, the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, and other groups have found that the fishing villages of Madagascar—a country with little history of natural resource regulation—are generally supportive of fishing regulations, an encouraging finding that bodes well for sustainable strategies needed to reduce poverty in the island nation.

Specifically, Malagasy fishers perceive restrictions on certain kinds of fishing gear as being beneficial for their livelihoods, according to the results of a survey conducted with ...

Kessler Foundation researchers study impact of head movement on fMRI data

2014-02-19

West Orange, NJ. February 19, 2014. Kessler Foundation researchers have shown that discarding data from subjects with multiple sclerosis (MS) who exhibit head movement during functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) may bias sampling away from subjects with lower cognitive ability. The study was published in the January issue of Human Brain Mapping. (Wylie GR, Genova H, DeLuca J, Chiaravalloti N, Sumowski JF. Functional MRI movers and shakers: Does subject-movement cause sampling bias.) Glenn Wylie, DPhil, is associate director of Neuroscience in Neuropsychology & Neuroscience ...

Clouds seen circling supermassive black holes

2014-02-19

Astronomers see huge clouds of gas orbiting supermassive black holes at the centers of galaxies. Once thought to be a relatively uniform, fog-like ring, the accreting matter instead forms clumps dense enough to intermittently dim the intense radiation blazing forth as these enormous objects condense and consume matter, they report in a paper to be published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, available online now.

Video depicting the swirling clouds is posted to YouTube http://youtu.be/QA8nzRkjOEw

Evidence for the clouds comes from records collected ...

Better cache management could improve chip performance, cut energy use

2014-02-19

Computer chips keep getting faster because transistors keep getting smaller. But the chips themselves are as big as ever, so data moving around the chip, and between chips and main memory, has to travel just as far. As transistors get faster, the cost of moving data becomes, proportionally, a more severe limitation.

So far, chip designers have circumvented that limitation through the use of "caches" — small memory banks close to processors that store frequently used data. But the number of processors — or "cores" — per chip is also increasing, which makes cache management ...

When faced with a hard decision, people tend to blame fate

2014-02-19

Life is full of decisions. Some, like what to eat for breakfast, are relatively easy. Others, like whether to move cities for a new job, are quite a bit more difficult. Difficult decisions tend to make us feel stressed and uncomfortable – we don't want to feel responsible if the outcome is less than desirable. New research suggests that we deal with such difficult decisions by shifting responsibility for the decision to fate.

The findings are published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

"Fate is a ubiquitous supernatural ...

UK failing to harness its bioenergy potential

2014-02-19

The UK could generate almost half its energy needs from biomass sources, including household waste, agricultural residues and home-grown biofuels by 2050, new research suggests.

Scientists from the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research at The University of Manchester found that the UK could produce up to 44% of its energy by these means without the need to import.

The study, published in Energy Policy journal, highlights the country's potential abundance of biomass resources that are currently underutilised and totally overlooked by the bioenergy sector. Instead, ...

Making nanoelectronics last longer for medical devices, 'cyborgs'

2014-02-19

The debut of cyborgs who are part human and part machine may be a long way off, but researchers say they now may be getting closer. In a study published in ACS' journal Nano Letters, they report development of a coating that makes nanoelectronics much more stable in conditions mimicking those in the human body. The advance could also aid in the development of very small implanted medical devices for monitoring health and disease.

Charles Lieber and colleagues note that nanoelectronic devices with nanowire components have unique abilities to probe and interface with living ...

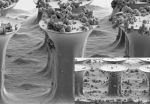

Gecko-inspired adhesion: Self-cleaning and reliable

2014-02-19

This news release is available in German. Geckos outclass adhesive tapes in one respect: Even after repeated contact with dirt and dust do their feet perfectly adhere to smooth surfaces. Researchers of the KIT and the Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, have now developed the first adhesive tape that does not only adhere to a surface as reliably as the toes of a gecko, but also possesses similar self-cleaning properties. Using such a tape, food packagings or bandages might be opened and closed several times. The results are published in the "Interface" journal of ...

Chemical leak in W.Va. shows gaps in research, policy

2014-02-19

The chemical leak that contaminated drinking water in the Charleston, W.Va., area last month put in sharp relief the shortcomings of the policies and research that apply to thousands of chemicals in use today. An article in Chemical & Engineering News (C&EN), the weekly magazine of the American Chemical Society, delves into the details of the accident that forced 300,000 residents to live on bottled water for days.

A team of C&EN reporters and editors note that the main chemical that leaked into the water supply is an obscure one called 4-methylcyclohexanemethanol, or ...