(Press-News.org) The steamiest places on the planet are getting warmer. Conservative estimates suggest that tropical areas can expect temperature increases of 3 degrees Celsius by the end of this century. Does global warming spell doom for rainforests? Maybe not. Carlos Jaramillo, staff scientist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, and colleagues report in the journal Science that nearly 60 million years ago rainforests prospered at temperatures that were 3-5 degrees higher and at atmospheric carbon dioxide levels 2.5 times today's levels.

"We're going to have a novel climate scenario," said Joe Wright, staff scientist at STRI, in a 2009 Smithsonian symposium on Threats to Tropical Forests. "It will be very hot and wet, and we don't know how these species are going to react." By looking back in time, Jaramillo and collaborators identified one example of a hot, wet climate: rainforests were doing very well.

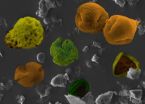

Researchers examined pollen trapped in rock cores and outcrops—from Colombia and Venezuela—formed before, during and after an abrupt global warming event called the

Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum that occurred 56.3 million years ago. The world warmed by 3-5 degrees C. Carbon dioxide levels doubled in only 10,000 years. Warm conditions lasted for the next 200,000 years.

Contrary to speculation that tropical forests could be devastated under these conditions, forest diversity increased rapidly during this warming event. New plant species evolved much faster than old species became extinct. Pollen from the passionflower plant family and the chocolate family, among others, were found for the first time.

"It is remarkable that there is so much concern about the effects of greenhouse conditions on tropical forests," said Klaus Winter, staff scientist at STRI. "However, these horror scenarios probably have some validity if increased temperatures lead to more frequent or more severe drought as some of the current predictions for similar scenarios suggest."

Evidence from this study indicates that moisture levels did not decrease significantly during the warming event. Overall results indicate that tropical forests fared very well during this short and intense warming period.

"The Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute celebrates '100 Years of Tropical Science in Panama' starting this year," said Eldredge Bermingham, STRI director. "Today, our scientists are working in more than 40 countries worldwide. We have the long-term and global monitoring experiments in place to begin to evaluate scenarios predicting the effects of climate change and other large-scale processes on tropical forests."

INFORMATION:

This research was supported by the Fundación Banco del la República de Colombia, the National Geographic Society, the Smithsonian Institution and the SI Women's Committee,

ICP-Ecopetrol S.A., the U.S. National Science Foundation and the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research.

The Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, headquartered in Panama City, Panama, is a unit of the Smithsonian Institution. The Institute furthers the understanding of tropical nature and its importance to human welfare, trains students to conduct research in the tropics and promotes conservation by increasing public awareness of the beauty and importance of tropical ecosystems. Website: www.stri.org. STRI Herbarium: www.stri.org/herbarium.

Ref. Jaramillo, C., Ochoa, D., Contreras, L., Pagani, M., Carvajal-Ortiz, H., Pratt, L., Krishnan, S., Cardona, A., Romero, M., Quiroz, L., Rodriguez, G., Rueda, M., de la Parra, F., Moron, S., Green, W., Bayona, G., Montes, C., Quintero, O., Ramirez, R., Mora, G., Schouten, S., Bermudez, Navarrete, R., Parra, F., Alvarán, M., Osorno, J., Crowley, J., Valencia, V., Vervoort, J. 2010. Effects of Rapid Global Warming at the Paleocene-Eocene Boundary on Neotropical Vegetation. Science.

Tropical forest diversity increased during ancient global warming event

2010-11-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Study finds the mind is a frequent, but not happy, wanderer

2010-11-12

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. -- People spend 46.9 percent of their waking hours thinking about something other than what they're doing, and this mind-wandering typically makes them unhappy. So says a study that used an iPhone web app to gather 250,000 data points on subjects' thoughts, feelings, and actions as they went about their lives.

The research, by psychologists Matthew A. Killingsworth and Daniel T. Gilbert of Harvard University, is described this week in the journal Science.

"A human mind is a wandering mind, and a wandering mind is an unhappy mind," Killingsworth and ...

Voluntary cooperation and monitoring lead to success

2010-11-12

FRANKFURT. Many imminent problems facing the world today, such as deforestation, overfishing, or climate change, can be described as commons problems. The solution to these problems requires cooperation from hundreds and thousands of people. Such large scale cooperation, however, is plagued by the infamous cooperation dilemma. According to the standard prediction, in which each individual follows only his own interests, large-scale cooperation is impossible because free riders enjoy common benefits without bearing the cost of their provision. Yet, extensive field evidence ...

New vaccine hope in fight against pneumonia and meningitis

2010-11-12

A new breakthrough in the fight against pneumonia, meningitis and septicaemia has been announced today by scientists in Dublin and Leicester.

The discovery will lead to a dramatic shift in our understanding of how the body's immune system responds to infection caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae and pave the way for more effective vaccines.

The collaborative research, jointly led by Dr Ed Lavelle from Trinity College Dublin and Dr Aras Kadioglu from the University of Leicester, with Dr Edel McNeela of TCD as its lead author, has been published in the international peer-reviewed ...

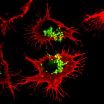

Scientists demystify an enzyme responsible for drug and food metabolism

2010-11-12

For the first time, scientists have been able to "freeze in time" a mysterious process by which a critical enzyme metabolizes drugs and chemicals in food. By recreating this process in the lab, a team of researchers has solved a 40-year-old puzzle about changes in a family of enzymes produced by the liver that break down common drugs such as Tylenol, caffeine, and opiates, as well as nutrients in many foods. The breakthrough discovery may help future researchers develop a wide range of more efficient and less-expensive drugs, household products, and other chemicals. The ...

Gene discovery suggests way to engineer fast-growing plants

2010-11-12

DURHAM, N.C. – Tinkering with a single gene may give perennial grasses more robust roots and speed up the timeline for creating biofuels, according to researchers at the Duke Institute for Genome Sciences & Policy (IGSP).

Perennial grasses, including switchgrass and miscanthus, are important biofuels crops and can be harvested repeatedly, just like lawn grass, said Philip Benfey, director of the IGSP Center for Systems Biology. But before that can happen, the root system needs time to get established.

"These biofuel crops usually can't be harvested until the second ...

Stanford scientists identify key protein controlling blood vessel growth into brains of mice

2010-11-12

STANFORD, Calif. — One protein single-handedly controls the growth of blood vessels into the developing brains of mice embryos, according to researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine. Understanding how the protein, a cellular receptor, functions could help clinicians battle brain tumors and stroke by choking off or supplementing vital blood-vessel development, and may enhance the delivery of drugs across the blood-brain barrier.

"The strength and specificity of this receptor's effects indicate that it could be a very important target," said Calvin Kuo, ...

Fortify HIT contracts with education and ethics to protect patient safety, say informatics experts

2010-11-12

Bethesda, MD—An original and progressive report on health information technology (HIT) vendors, their customers and patients, published online today, makes ground-breaking recommendations for new practices that target the reduction or elimination of tensions that currently mar relationships between many HIT vendors and their customers, specifically with regard to indemnity and error management of HIT systems. In light of the Obama Administration's $19 billion investment in HIT, paid out in ARRA stimulus funds, these recommendations are particularly significant in helping ...

Graphene's strength lies in its defects

2010-11-12

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — The website of the Nobel Prize shows a cat resting in a graphene hammock. Although fictitious, the image captures the excitement around graphene, which, at one atom thick, is the among the thinnest and strongest materials ever produced.

A significant obstacle to realizing graphene's potential lies in creating a surface large enough to support a theoretical sleeping cat. For now, material scientists stitch individual graphene sheets together to create sheets that are large enough to investigate possible applications. Just as sewing ...

New analysis explains formation of bulge on far side of moon

2010-11-12

SANTA CRUZ, CA--A bulge of elevated topography on the farside of the moon--known as the lunar farside highlands--has defied explanation for decades. But a new study led by researchers at the University of California, Santa Cruz, shows that the highlands may be the result of tidal forces acting early in the moon's history when its solid outer crust floated on an ocean of liquid rock.

Ian Garrick-Bethell, an assistant professor of Earth and planetary sciences at UC Santa Cruz, found that the shape of the moon's bulge can be described by a surprisingly simple mathematical ...

Contact among age groups key to understanding whooping cough spread and control

2010-11-12

ANN ARBOR, Mich.---Strategies for preventing the spread of whooping cough---on the rise in the United States and several other countries in recent years---should take into account how often people in different age groups interact, research at the University of Michigan suggests.

The findings appear in the Nov. 12 issue of the journal Science.

Thanks to widespread childhood vaccination, whooping cough (pertussis) once seemed to be under control. But the illness, which in infants causes violent, gasping coughing spells, has made a comeback in some developed countries ...