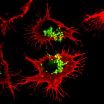

(Press-News.org) Using induced pluripotent stem cells from patients with Rett syndrome, scientists at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine have created functional neurons that provide the first human cellular model for studying the development of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and could be used as a tool for drug screening, diagnosis and personalized treatment.

The research, led by Alysson R. Muotri, PhD, assistant professor of pediatrics, will be published in the November 12 issue of the journal Cell.

"This work is important because it puts us in a translational mode," said Muotri. "It helps expand and deepen our understanding of autism, from behavioral disorder to developmental brain disorder. We can now look for and test drugs and therapies and see what happens at a cellular and molecular level. That's something we've never been able to do with human autistic neurons before."

Rett (RTT) syndrome is a neurological disorder in which affected newborns display normal development until six months to 1½ years of age, "after which behavioral symptoms begin to emerge," Muotri said. "Progressively, motor functions become impaired. There may be hypotonia or low muscle tone, seizures, diminished social skills and other autistic behaviors."

RTT was the focus of the research because its genetic underpinnings are well-understood. The condition is caused by mutations to the X-linked gene encoding a protein called MeCP2. By knocking out or adding the relevant gene in animal models, researchers can create the damaging effects of RTT or rescue impaired cells.

The new research goes further. Muotri and colleagues at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies and Pennsylvania State University developed a culture system using induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) derived from RTT patient's skin fibroblasts – cells that typically give rise to connective tissues. Instead, the human RTT-iPSCs were reprogrammed to generate functional neurons that, compared to normal control cells, featured fewer synapses, reduced spine density, smaller soma size, altered calcium signaling and electrophysiological defects – all indications that the deleterious alterations to human RTT neurons begin early in development.

The scientists also exposed human RTT-iPSCs to insulin growth factor 1 or IGF1. In a mouse model with RTT syndrome, IGF1 has been shown to improve symptoms, suggesting the protein might have similar potential for treating RTT and other neurological disorders in people. Muotri said IGF1 appeared to rescue some RTT-iPSCs, reverting some neuronal defects, though exactly how IGF1 works remains unknown and requires further investigation.

"This suggests, however, that synaptic deficiencies in Rett syndrome, and likely other autism spectrum disorders, may not be permanent," Muotri said.

Muotri said creation of a human RTT cell culture provides a new and unexplored developmental window before disease onset and possibly a common model for future studies of ASDs.

INFORMATION:

Co-authors of the paper are Maria C.N. Marchetto, Diana Yu, Yangling Mu and Fred Gage of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies; Cassiano Carromeu and Allan Acab of the UCSD School of Medicine, Department of Pediatrics/Rady Children's Hospital, Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine and Stem Cell Program; Gene Yeo at the UCSD School of Medicine, Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine and Stem Cell Program; and Gong Chen at Pennsylvania State University, Department of Biology.

This work was supported by the Emerald Foundation Young Investigator Award, the National Institutes of Health through the NIH Director's New Innovator Award Program, the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine, The Lookout Fund and the Picower Foundation.

Watch a video about this research at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_AU5skJVbhY.

About autism

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a range of complex, varying neurodevelopment disorders characterized by social impairments, communication difficulties and restricted, repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behavior. It is not known what causes ASD. Scientists have identified a number of genes associated with the disorder, but environmental factors likely play a role too.

Autistic disorder (sometimes called autism or classical ASD) is the most severe form. Milder conditions include Asperger syndrome, Rett syndrome, Childhood Disintegrative Disorder and Pervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (usually referred to as PDD-NOS).

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports the prevalence of autism to be approximately 1 in every 110 births in the United States. An estimated 1.5 million Americans live with the effects of ASD, which occurs in all ethnic and socioeconomic groups and affects every age group, though males are four times more likely to have ASD than females.

UCSD researchers create autistic neuron model

2010-11-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New urine test could diagnose acute kidney injury

2010-11-12

The presence of certain markers in the urine might be a red flag for acute kidney injury (AKI), according to a study appearing in an upcoming issue of the Journal of the American Society Nephrology (JASN). The results suggest that a simple urine test could help prevent cases of kidney failure.

Unlike heart or brain injuries, which show obvious outward signs, physical symptoms are not typically present with AKI. Researchers have been looking for markers of AKI, with the hope that early detection will lead to early therapy to prevent kidney failure. Richard Zager, MD (Clinical ...

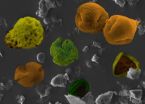

Keeping the daily clock ticking in a fluctuating environment: Hints from a green alga

2010-11-12

Researchers in France have uncovered a mechanism which explains how biological clocks accurately synchronize to the day/night cycle despite large fluctuations in light intensity during the day and from day to day. Following the identification of two central "clock genes" of a green alga, Ostreococcus tauri, a mathematical model reproducing their daily activity profiles has revealed that their internal clock is influenced by the naturally varying light levels throughout the day only at periods when it needs resetting. The results found by the biologists at Oceanologic Observatory ...

Cats show perfect balance even in their lapping

2010-11-12

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — Cat fanciers everywhere appreciate the gravity-defying grace and exquisite balance of their feline friends. But do they know those traits extend even to the way cats lap milk?

Researchers at MIT, Virginia Tech and Princeton University analyzed the way domestic and big cats lap and found that felines of all sizes take advantage of a perfect balance between two physical forces. The results will be published in the November 11 online issue of the journal Science.

It was known that when they lap, cats extend their tongues straight down toward the bowl ...

New explanation for the origin of high species diversity

2010-11-12

PHILADELPHIA—An international team of scientists, including a leading evolutionary biologist from the Academy of Natural Sciences, have reset the agenda for future research in the highly diverse Amazon region by showing that the extraordinary diversity found there is much older than generally thought.

The findings from this study, which draws on research by the Academy's Dr. John Lundberg and other scientists, were published as a review article in this week's edition of Science. The study shows that Amazonian diversity has evolved as by-product of the Andean mountain ...

Tropical forest diversity increased during ancient global warming event

2010-11-12

The steamiest places on the planet are getting warmer. Conservative estimates suggest that tropical areas can expect temperature increases of 3 degrees Celsius by the end of this century. Does global warming spell doom for rainforests? Maybe not. Carlos Jaramillo, staff scientist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, and colleagues report in the journal Science that nearly 60 million years ago rainforests prospered at temperatures that were 3-5 degrees higher and at atmospheric carbon dioxide levels 2.5 times today's levels.

"We're going to have a novel climate ...

Study finds the mind is a frequent, but not happy, wanderer

2010-11-12

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. -- People spend 46.9 percent of their waking hours thinking about something other than what they're doing, and this mind-wandering typically makes them unhappy. So says a study that used an iPhone web app to gather 250,000 data points on subjects' thoughts, feelings, and actions as they went about their lives.

The research, by psychologists Matthew A. Killingsworth and Daniel T. Gilbert of Harvard University, is described this week in the journal Science.

"A human mind is a wandering mind, and a wandering mind is an unhappy mind," Killingsworth and ...

Voluntary cooperation and monitoring lead to success

2010-11-12

FRANKFURT. Many imminent problems facing the world today, such as deforestation, overfishing, or climate change, can be described as commons problems. The solution to these problems requires cooperation from hundreds and thousands of people. Such large scale cooperation, however, is plagued by the infamous cooperation dilemma. According to the standard prediction, in which each individual follows only his own interests, large-scale cooperation is impossible because free riders enjoy common benefits without bearing the cost of their provision. Yet, extensive field evidence ...

New vaccine hope in fight against pneumonia and meningitis

2010-11-12

A new breakthrough in the fight against pneumonia, meningitis and septicaemia has been announced today by scientists in Dublin and Leicester.

The discovery will lead to a dramatic shift in our understanding of how the body's immune system responds to infection caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae and pave the way for more effective vaccines.

The collaborative research, jointly led by Dr Ed Lavelle from Trinity College Dublin and Dr Aras Kadioglu from the University of Leicester, with Dr Edel McNeela of TCD as its lead author, has been published in the international peer-reviewed ...

Scientists demystify an enzyme responsible for drug and food metabolism

2010-11-12

For the first time, scientists have been able to "freeze in time" a mysterious process by which a critical enzyme metabolizes drugs and chemicals in food. By recreating this process in the lab, a team of researchers has solved a 40-year-old puzzle about changes in a family of enzymes produced by the liver that break down common drugs such as Tylenol, caffeine, and opiates, as well as nutrients in many foods. The breakthrough discovery may help future researchers develop a wide range of more efficient and less-expensive drugs, household products, and other chemicals. The ...

Gene discovery suggests way to engineer fast-growing plants

2010-11-12

DURHAM, N.C. – Tinkering with a single gene may give perennial grasses more robust roots and speed up the timeline for creating biofuels, according to researchers at the Duke Institute for Genome Sciences & Policy (IGSP).

Perennial grasses, including switchgrass and miscanthus, are important biofuels crops and can be harvested repeatedly, just like lawn grass, said Philip Benfey, director of the IGSP Center for Systems Biology. But before that can happen, the root system needs time to get established.

"These biofuel crops usually can't be harvested until the second ...