(Press-News.org) If a driver is traveling to New York City, I-95 might be their route of choice. But they could also take I-78, I-87 or any number of alternate routes. Most cancers begin similarly, with many possible routes to the same disease. A new study found evidence that assessing the route to cancer on a case-by-case basis might make more sense than basing a patient's cancer treatment on commonly disrupted genes and pathways.

The study found little or no overlap in the most prominent genetic malfunction associated with each individual patient's disease compared to malfunctions shared among the group of cancer patients as a whole.

"This paper argues for the importance of personalized medicine, where we treat each person by looking for the etiology of the disease in patients individually," said John McDonald, a professor in the School of Biology at the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta. "The findings have ramifications on how we might best optimize cancer treatments as we enter the era of targeted gene therapy."

The research was published February 11 online in the journal PANCREAS and was funded by the Georgia Tech Foundation and the St. Joseph's Mercy Foundation.

In the study, researchers collected cancer and normal tissue samples from four patients with pancreatic cancer and also analyzed data from eight other pancreatic cancer patients that had been previously reported in the scientific literature by a separate research group.

McDonald's team compiled a list of the most aberrantly expressed genes in the cancer tissues isolated from these patients relative to adjacent normal pancreatic tissue.

The study found that collectively 287 genes displayed significant differences in expression in the cancers vs normal tissues. Twenty-two cellular pathways were enriched in cancer samples, with more than half related to the body's immune response. The researchers ran statistical analyses to determine if the genes most significantly abnormally expressed on an individual patient basis were the same as those identified as most abnormally expressed across the entire group of patients.

The researchers found that the molecular profile of each individual cancer patient was unique in terms of the most significantly disrupted genes and pathways.

"If you're dealing with a disease like cancer that can be arrived at by multiple pathways, it makes sense that you're not going to find that each patient has taken the same path," McDonald said.

Although the researchers found that some genes that were commonly disrupted in all or most of the patients examined, these genes were not among the most significantly disrupted in any individual patient.

"By and large, there appears to be a lot of individuality in terms of the molecular basis of pancreatic cancer," said McDonald, who also serves as the director of the Integrated Cancer Research Center and as the chief scientific officer of the Ovarian Cancer Institute.

Though the study is small, it raises questions about the validity of pinpointing the most important gene or pathway underlying a disease by pooling data from multiple patients, McDonald said. He favors individual profiling as the preferred method for initiating treatment.

The cost of a molecular profiling analysis to transcribe the DNA sequences of exons — the parts of the genome that carry instructions for proteins — is about $2,000 (exons account for about two percent of a cell's total DNA). That's about half the cost of this analysis five years ago, McDonald said, and a $1,000 molecular profiling analysis might not be far off.

"As costs continue to come down, personalized molecular profiling will be carried out on more cancer patients," McDonald said.

Yet cost isn't the only limiting factor, McDonald said. Scientists and doctors have to shift their paradigm on how they use molecular profiling to treat cancer.

"Are you going to believe what you see for one patient or are you going to say, 'I can't interpret that data until I group it together with 100 other patients and find what's in common among them,'" McDonald said. "For any given individual patient there may be mutant genes or aberrant expression patterns that are vitally important for that person's cancer that aren't present in other patients' cancers."

Future work in McDonald's lab will see if this pattern of individuality is repeated in larger studies and in patients with different cancers. The group is currently working on a genomic profiling analysis of patients with ovarian and lung cancers.

"If there are multiple paths, then maybe individual patients are getting cancer from alternative routes," McDonald said. "If that's the case, we should do personalized profiling on each patient before we make judgments on the treatment for that patient."

INFORMATION:

Loukia Lili, of Georgia Tech's Integrated Cancer Research Center, School of Biology, and Parker H. Petit Institute of Bioengineering and Biosciences, was the study's first author. Co-authors included Lilya Matyunina and DeEtte Walker of Georgia Tech, and George Daneker, MD, of the Cancer Treatment Centers of America SE Regional Facility in Newnan, Ga.

This research is supported by the Georgia Tech Foundation and the St. Joseph's Mercy Foundation. Any conclusions or opinions are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the sponsoring agencies.

CITATION: Loukia N. Lili, et al., "Evidence for the Importance of Personalized Molecular Profiling in Pancreatic Cancer," (PANCREAS, February 2014). (http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MPA.0000000000000020).

Personalized medicine best way to treat cancer, study argues

2014-02-24

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

On the road to Mottronics

2014-02-24

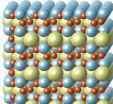

"Mottronics" is a term seemingly destined to become familiar to aficionados of electronic gadgets. Named for the Nobel laureate Nevill Francis Mott, Mottronics involve materials – mostly metal oxides - that can be induced to transition between electrically conductive and insulating phases. If these phase transitions can be controlled, Mott materials hold great promise for future transistors and memories that feature higher energy efficiencies and faster switching speeds than today's devices. A team of researchers working at Berkeley Lab's Advanced Light Source (ALS) have ...

New ideas change your brain cells: UBC research

2014-02-24

A new University of British Columbia study identifies an important molecular change that occurs in the brain when we learn and remember.

Published this month in Nature Neuroscience, the research shows that learning stimulates our brain cells in a manner that causes a small fatty acid to attach to delta-catenin, a protein in the brain. This biochemical modification is essential in producing the changes in brain cell connectivity associated with learning, the study finds.

In animal models, the scientists found almost twice the amount of modified delta-catenin in the brain ...

Bushfires continue to plague Victoria, Australia

2014-02-24

Reports coming from Australia are more positive than negative now with regards to the Morwell fire, but officials say they still have a "long way to go." Considerable progress has been made in extinguishing the fire, but there is still significant heat that continues to generate smoke from the open mine. Fire activity has been cut in half since February 11, but there are still "weeks of firefighting ahead" according to Craig Lapsley, Fire Services Commissioner on the County Fire Authority website.

According to the Australian News, "The [Morwell] fire, which started ...

Study of Hispanic/Latino health presents initial findings

2014-02-24

February 24, 2014 – (BRONX, NY) –One in every six people in the U.S. is Hispanic/Latino and as a group they live longer than non-Hispanic whites (81.4 years vs. 78.8 years). Yet, despite their strong representation and relative longevity, little is understood about this group's health conditions and behaviors.

The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL), the landmark research study of Hispanic/Latino health funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), has released initial findings that show significant variations in disease prevalence and health ...

Researcher builds a better job performance review

2014-02-24

MANHATTAN -- A critical job performance evaluation can have a negative effect on any employee, a Kansas State University researcher has found.

By studying how people view positive or negative feedback, Satoris Culbertson, assistant professor of management, has determined that nobody -- even people who are motivated to learn -- likes negative performance reviews. Culbertson is developing ways to help managers improve the process for reviewing employees.

Culbertson and collaborators at Eastern Kentucky University and Texas A&M University surveyed more than 200 staffers ...

Now it will become cheaper to make second-generation biofuel for our cars

2014-02-24

Producing second-generation biofuel from dead plant tissue is environmetally friendly - but it is also expensive because the process as used today needs expensive enzymes, and large companies dominate this market. Now a Danish/Iraqi collaboration presents a new technique that avoids the expensive enzymes. The production of second generation biofuels thus becomes cheaper, probably attracting many more producers and competition, and this may finally bring the price down.

The world's need for fuel will persist, also when the Earth's deposits of fossil fuels run out. Bioethanol, ...

Biomedical bleeding affects horseshoe crab behavior

2014-02-24

DURHAM, N.H. – New research from Plymouth State University and the University of New Hampshire indicates that collecting and bleeding horseshoe crabs for biomedical purposes causes short-term changes in their behavior and physiology that could exacerbate the crabs' population decline in parts of the east coast.

Each year, the U.S. biomedical industry harvests the blue blood from almost half a million living horseshoe crabs for use in pharmaceuticals — most notably, a product called Limulus amebocyte lysate (LAL), used to ensure vaccines and medical equipment are free ...

Significant discrepancies between FISH and IHC results for ALK testing

2014-02-24

DENVER –The findings of a recent study indicate that routine testing with both fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) and immunohistochemistry (IHC) may enhance the detection of ALK-positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Accurate determination of ALK-positive tumors is necessary to identify patients with advanced NSCLC who are most likely to benefit from targeted therapy with an ALK inhibitor.

The discovery of ALK rearrangement in about 1% to 7% of NSCLCs led to the development of ALK inhibitors, such as crizotinib, which have significantly improved treatment ...

Researchers find flowing water can slow down bacteria

2014-02-24

In a surprising new finding, researchers have discovered that bacterial movement is impeded in flowing water, enhancing the likelihood that the microbes will attach to surfaces. The new work could have implications for the study of marine ecosystems, and for our understanding of how infections take hold in medical devices.

The findings, the result of microscopic analysis of bacteria inside microfluidic devices, were made by MIT postdoc Roberto Rusconi, former MIT postdoc Jeffrey Guasto (now an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at Tufts University), and Roman ...

Tip to dieters: Beware of friends and late night cravings

2014-02-24

There's more to dieting than just sheer willpower and self-control. The presence of friends, late night cravings or the temptation of alcohol can often simply be too strong to resist. Research led by Heather McKee of the University of Birmingham in the UK monitored the social and environmental factors that make people, who are following weight management programs, cheat. The study¹ is published in the Springer journal Annals of Behavioral Medicine.²

Eighty people who were either part of a weight-loss group or were dieting on their own participated in the one-week study. ...