(Press-News.org) COLUMBUS, Ohio – New research suggests that a protein only recently linked to cancer has a significant effect on the risk that breast cancer will spread, and that lowering the protein's level in cell cultures and mice reduces chances for the disease to extend beyond the initial tumor.

The team of medical and engineering researchers at The Ohio State University previously determined that modifying a single gene to reduce this protein's level in breast cancer cells lowered the cells' ability to migrate away from the tumor site.

In a new study published in the journal PLOS ONE, the researchers reported similar findings in animals. The study showed that mice implanted with breast cancer cells lacking the protein developed small, self-contained tumors consisting of cells that didn't leave the tumor. In contrast, mice implanted with cancer cells containing the protein developed larger, irregular masses and showed signs that cancer cells had invaded the surrounding tissue.

The research suggests that reducing production of the protein, called myoferlin, affects cancer cells in two primary ways: by changing the activation of many genes involved in metastasis in favor of normal cell behavior, and by altering mechanical properties of cancer cells – including their shape and ability to invade – so they are more likely to remain nested together rather than breaking away to travel to other tissues.

Myoferlin's influence on both molecular and mechanical processes in breast cancer cells suggests that diagnostic methods and perhaps even treatments eventually might be tailored to patients based on protein levels and mechanical properties in cells detected in tumors, researchers say. Though clinical applications are still years away, the scientists say the two-pronged approach to research on the protein's effects broadens its potential usefulness in diagnostics and therapies.

"Theoretically, if a patient had a tumor in which the myoferlin level was low, it would be defined as small and a surgeon could remove it and it wouldn't metastasize. That's the nodule type of tumor we saw in the mice with the silenced protein," said Douglas Kniss, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Ohio State's Wexner Medical Center and senior author of the study.

Kniss and colleagues used subtypes of triple-negative breast cancer cells for the study – one of the most lethal forms of breast cancer because of its likelihood to spread. "Since triple-negative cells are the most dangerous, we do wonder if this protein is relevant to only the most dangerous types of cancers, or if it is more generalized. We don't know the answer at the moment," he said.

Kniss teamed with co-author Samir Ghadiali, associate professor of biomedical engineering at Ohio State, to hone in on the mechanical aspects of this work. Understanding the protein's effects on genes is just one piece of the puzzle: The effects of physical and mechanical forces on cancer progression is a burgeoning, but still new, area of research.

"We're seeing now that the mechanics are going to drive whether cancer cells can migrate faster or slower or break away or not. The mechanics have the possibility of being a more specific diagnostic marker," Ghadiali said.

The protein's role in cancer was an unexpected finding in Kniss's lab because only a handful of studies had described the connection before his group pursued this line of research.

"We had guilt by suspicion," said Kniss, also director of the Laboratory of Perinatal Research at Ohio State. "So we decided to knock out the gene for myoferlin in breast cancer cells and the cells did weird things. They didn't invade very well."

At the core of this cell behavior is how the loss of that single gene changes activation levels of dozens of other genes, suppressing genes associated with metastatic disease and increasing activity of genes linked to normal tissue. But the cells also changed shape and other properties in the absence of the protein in ways that reduced the likelihood that they would travel away from the tumor – a sign that myoferlin not only changes genes in cancer cells, but also alters the cells' mechanical properties.

In this most recent study, the researchers analyzed the various mechanical changes to breast cancer cells in which myoferlin levels were dramatically reduced compared to normal breast cancer cells. The scientists used a modified virus to deliver pieces of RNA to block the myoferlin gene.

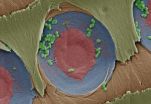

When the protein is present, these cells that start out round and stuck together in a pattern resembling cobblestones become irregularly shaped and tend to detach from the tumor site in an uncoordinated way – hallmarks of metastasis. They also lose their "stickiness," or adhesion property, making it easier for them to break away from neighboring cells.

In contrast, cancer cells lacking the protein tend to retain their usual shape and stickiness, and stay together in a group if they make any movement – all features that would cause a tumor to remain intact for surgical removal.

The most surprising mechanics-related finding concerned the cells' stiffness. The prevailing theory about metastatic disease suggests that metastatic cancer cells must be soft, or pliable like Play-Doh, to squeeze through tissue, blood vessels and more tissue as they travel to and invade distant locations in the body. But the tumor cells containing normal levels of myoferlin – the cells likely to migrate – were found to be stiff rather than soft, similar to hardened modeling clay.

So the new thinking is that under typical metastatic conditions, the cells must initially stiffen up to make it possible to leave the tumor, and then soften to ease their travels through the body, said Ghadiali, also an investigator in the Davis Heart and Lung Research Institute.

"We believe the cells lacking myoferlin are made softer in the tumor so they can't physically detach away. So making cells in the primary tumor softer might be a way to prevent metastasis," he said. "And that suggests that seeing softer cells in circulation means it's almost too late. You've already got some advanced disease going on."

This is the third related study published by the Ohio State team. Kniss is either an author or a peer reviewer of the five most recent studies about myoferlin's link to cancer.

The researchers next will turn to analyzing the presence of myoferlin in samples from numerous human tumor types available in an Ohio State tissue bank, which will allow them to compare protein levels in tumors to clinical outcomes for the patients who provided the samples.

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation and the Ohio State University Perinatal Research and Development Fund.

Co-authors include Leonithas Volakis, Cosmin Mihai (now with Pacific Northwest National Laboratory), Christopher Ahn (now with the University of California, San Diego), Heather Powell (now with Ohio State's Department of Mechanical Engineering) and Rachel Zielinski of Ohio State's Department of Biomedical Engineering; Ruth Li, William Ackerman IV, Meagan Bechel (now with Northwestern University) and Taryn Summerfield of Ohio State's Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology; and Thomas Rosol of Ohio State's Department of Veterinary Biosciences.

Contact: Douglas Kniss, (614) 293-4496; Kniss.1@osu.edu or Samir Ghadiali, (614) 247-1849; Ghadiali.1@osu.edu

Written by Emily Caldwell, (614) 292-8310; Caldwell.151@osu.edu

Breast cancer cells less likely to spread when one gene is turned off

Research in cells, mice explores protein previously unrecognized in cancer

2014-02-27

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

One gene influences recovery from traumatic brain injury

2014-02-27

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Researchers report that one change in the sequence of the BDNF gene causes some people to be more impaired by traumatic brain injury (TBI) than others with comparable wounds.

The study, described in the journal PLOS ONE, measured general intelligence in a group of 156 Vietnam War veterans who suffered penetrating head wounds during the war. All of the study subjects had damage to the prefrontal cortex, a brain region behind the forehead that is important to cognitive tasks such as planning, problem-solving, self-restraint and complex thought.

The ...

Caesarean babies are more likely to become overweight as adults

2014-02-27

Babies born by caesarean section are more likely to be overweight or obese as adults, according to a new analysis.

The odds of being overweight or obese are 26 per cent higher for adults born by caesarean section than those born by vaginal delivery, the study found (see footnote).

The finding, reported in the journal PLOS ONE, is based on combined data from 15 studies with over 38,000 participants.

The researchers, from Imperial College London, say there are good reasons why many women should have a C-section, but mothers choosing a caesarean should be aware that ...

Cows are smarter when raised in pairs

2014-02-27

Cows learn better when housed together, which may help them adjust faster to complex new feeding and milking technologies on the modern farm, a new University of British Columbia study finds.

The research, published today in PLOS ONE, shows dairy calves become better at learning when a "buddy system" is in place. The study also provides the first evidence that the standard practice of individually housing calves is associated with certain learning difficulties.

"Pairing calves seems to change the way these animals are able to process information," said Dan Weary, corresponding ...

Impact on mummy skull suggests murder

2014-02-27

Blunt force trauma to the skull of a mummy with signs of Chagas disease may support homicide as cause of death, which is similar to previously described South American mummies, according to a study published February 26, 2014 in PLOS ONE by Stephanie Panzer from Trauma Center Murau, Germany, and colleagues, a study that has been directed by the paleopathologist Andreas Nerlich from Munich University.

For over a hundred years, the unidentified mummy has been housed in the Bavarian State Archeological Collection in Germany. To better understand its origin and life history, ...

Tree branch filters water

2014-02-27

A small piece of freshly cut sapwood can filter out more than 99 percent of the bacteria E. coli from water, according to a paper published in PLOS ONE on February 26, 2014 by Michael Boutilier and Jongho Lee and colleagues from MIT.

Researchers were interested in studying low-cost and easy-to-make options for filtering dirty water, a major cause of human mortality in the developing world. The sapwood of pine trees contains xylem, a porous tissue that moves sap from a tree's roots to its top through a system of vessels and pores. To investigate sapwood's water-filtering ...

Waterbirds' hunt aided by specialized tail

2014-02-27

The convergent evolution of tail shapes in diving birds may be driven by foraging style, according to a paper published in PLOS ONE on February 26, 2014 by Ryan Felice and Patrick O'Connor from Ohio University.

Birds use their wings and specialized tail to maneuver through the air while flying. It turns out that the purpose of a bird's tail may have also aided in their diversification by allowing them to use a greater variety of foraging strategies. To better understand the relationship between bird tail shape and foraging strategy, researchers examined the tail skeletal ...

MIT researchers make a water filter from the sapwood in tree branches

2014-02-27

If you've run out of drinking water during a lakeside camping trip, there's a simple solution: Break off a branch from the nearest pine tree, peel away the bark, and slowly pour lake water through the stick. The improvised filter should trap any bacteria, producing fresh, uncontaminated water.

In fact, an MIT team has discovered that this low-tech filtration system can produce up to four liters of drinking water a day — enough to quench the thirst of a typical person.

In a paper published this week in the journal PLoS ONE, the researchers demonstrate that a small ...

Study finds social-media messages grow terser during major events

2014-02-27

In the last year or two, you may have had some moments — during elections, sporting events, or weather incidents — when you found yourself sending out a flurry of messages on social media sites such as Twitter.

You are not alone, of course: Such events generate a huge volume of social-media activity. Now a new study published by researchers in MIT's Senseable City Lab shows that social-media messages grow shorter as the volume of activity rises at these particular times.

"This helps us better understand what is going on — the way we respond to things becomes faster ...

Humans have a poor memory for sound

2014-02-27

Remember that sound bite you heard on the radio this morning? The grocery items your spouse asked you to pick up? Chances are, you won't.

Researchers at the University of Iowa have found that when it comes to memory, we don't remember things we hear nearly as well as things we see or touch.

"As it turns out, there is merit to the Chinese proverb 'I hear, and I forget; I see, and I remember," says lead author of the study and UI graduate student, James Bigelow.

"We tend to think that the parts of our brain wired for memory are integrated. But our findings indicate ...

DNA test better than standard screens in identifying fetal chromosome abnormalities

2014-02-27

BOSTON (Feb. 27) – A study in this week's New England Journal of Medicine potentially has significant implications for prenatal testing for major fetal chromosome abnormalities. The study found that in a head-to-head comparison of noninvasive prenatal testing using cell free DNA (cfDNA) to standard screening methods, cfDNA testing (verifi® prenatal test, Illumina, Inc.) significantly reduced the rate of false positive results and had significantly higher positive predictive values for the detection of fetal trisomies 21 and 18.

A team of scientists, led by Diana W. Bianchi, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

New data on spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) – a common cause of heart attacks in younger women

How root growth is stimulated by nitrate: Researchers decipher signalling chain

Scientists reveal our best- and worst-case scenarios for a warming Antarctica

Cleaner fish show intelligence typical of mammals

AABNet and partners launch landmark guide on the conservation of African livestock genetic resources and sustainable breeding strategies

Produce hydrogen and oxygen simultaneously from a single atom! Achieve carbon neutrality with an 'All-in-one' single-atom water electrolysis catalyst

Sleep loss linked to higher atrial fibrillation risk in working-age adults

Visible light-driven deracemization of α-aryl ketones synergistically catalyzed by thiophenols and chiral phosphoric acid

Most AI bots lack basic safety disclosures, study finds

How competitive gaming on discord fosters social connections

CU Anschutz School of Medicine receives best ranking in NIH funding in 20 years

Mayo Clinic opens patient information office in Cayman Islands

Phonon lasers unlock ultrabroadband acoustic frequency combs

Babies with an increased likelihood of autism may struggle to settle into deep, restorative sleep, according to a new study from the University of East Anglia.

National Reactor Innovation Center opens Molten Salt Thermophysical Examination Capability at INL

International Progressive MS Alliance awards €6.9 million to three studies researching therapies to address common symptoms of progressive MS

Can your soil’s color predict its health?

Biochar nanomaterials could transform medicine, energy, and climate solutions

Turning waste into power: scientists convert discarded phone batteries and industrial lignin into high-performance sodium battery materials

PhD student maps mysterious upper atmosphere of Uranus for the first time

Idaho National Laboratory to accelerate nuclear energy deployment with NVIDIA AI through the Genesis Mission

Blood test could help guide treatment decisions in germ cell tumors

New ‘scimitar-crested’ Spinosaurus species discovered in the central Sahara

“Cyborg” pancreatic organoids can monitor the maturation of islet cells

Technique to extract concepts from AI models can help steer and monitor model outputs

Study clarifies the cancer genome in domestic cats

Crested Spinosaurus fossil was aquatic, but lived 1,000 kilometers from the Tethys Sea

MULTI-evolve: Rapid evolution of complex multi-mutant proteins

A new method to steer AI output uncovers vulnerabilities and potential improvements

Why some objects in space look like snowmen

[Press-News.org] Breast cancer cells less likely to spread when one gene is turned offResearch in cells, mice explores protein previously unrecognized in cancer