(Press-News.org) Blunt force trauma to the skull of a mummy with signs of Chagas disease may support homicide as cause of death, which is similar to previously described South American mummies, according to a study published February 26, 2014 in PLOS ONE by Stephanie Panzer from Trauma Center Murau, Germany, and colleagues, a study that has been directed by the paleopathologist Andreas Nerlich from Munich University.

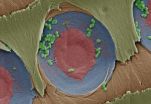

For over a hundred years, the unidentified mummy has been housed in the Bavarian State Archeological Collection in Germany. To better understand its origin and life history, scientists examined the skeleton, organs, and ancient DNA using a myriad of techniques: anthropological investigation, a complete body CT scan, isotope analysis, tissue histology, molecular identification of ancient parasitic DNA, and forensic injury reconstruction.

Radiocarbon dated to around 1450 - 1640 AD, skeletal examination indicated that the mummy was likely 20-25 years old at the time of her death, and her skull exhibits typical Incan-type skull formations. Fiber from her hair bands appear to originate from South American llama or alpaca. Isotope analysis of nitrogen and carbon in her hair reveal a diet likely comprising maize and seafood, which, along with other evidence suggest South American origin and a life spent in coastal Peru or Chile. The mummy also showed significant thickening of the heart, intestines, and the rectum, features typically associated with chronic Chagas disease, a tropical parasitic infection. DNA analysis of parasites found in rectum tissue samples also support chronic Chagas disease, a condition she probably had since early infancy. The skull structure where a massive skull and face trauma occurred, suggests the trauma was acquired prior to death, and indicates massive central blunt force. The young Incan may have been victim of a ritual homicide, as has been observed in other South American mummies.

INFORMATION:

Citation: Panzer S, Peschel O, Haas-Gebhard B, Bachmeier BE, Pusch CM, et al. (2014) Reconstructing the Life of an Unknown (ca. 500 Years-Old South American Inca) Mummy – Multidisciplinary Study of a Peruvian Inca Mummy Suggests Severe Chagas Disease and Ritual Homicide. PLoS ONE 9(2): e89528. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0089528

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no support or funding to report.

Competing Interest Statement: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

PLEASE LINK TO THE SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE IN ONLINE VERSIONS OF YOUR REPORT (URL goes live after the embargo ends): http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089528

Impact on mummy skull suggests murder

Analysis of archived mummy reveals murdered young female with Chagas disease

2014-02-27

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Tree branch filters water

2014-02-27

A small piece of freshly cut sapwood can filter out more than 99 percent of the bacteria E. coli from water, according to a paper published in PLOS ONE on February 26, 2014 by Michael Boutilier and Jongho Lee and colleagues from MIT.

Researchers were interested in studying low-cost and easy-to-make options for filtering dirty water, a major cause of human mortality in the developing world. The sapwood of pine trees contains xylem, a porous tissue that moves sap from a tree's roots to its top through a system of vessels and pores. To investigate sapwood's water-filtering ...

Waterbirds' hunt aided by specialized tail

2014-02-27

The convergent evolution of tail shapes in diving birds may be driven by foraging style, according to a paper published in PLOS ONE on February 26, 2014 by Ryan Felice and Patrick O'Connor from Ohio University.

Birds use their wings and specialized tail to maneuver through the air while flying. It turns out that the purpose of a bird's tail may have also aided in their diversification by allowing them to use a greater variety of foraging strategies. To better understand the relationship between bird tail shape and foraging strategy, researchers examined the tail skeletal ...

MIT researchers make a water filter from the sapwood in tree branches

2014-02-27

If you've run out of drinking water during a lakeside camping trip, there's a simple solution: Break off a branch from the nearest pine tree, peel away the bark, and slowly pour lake water through the stick. The improvised filter should trap any bacteria, producing fresh, uncontaminated water.

In fact, an MIT team has discovered that this low-tech filtration system can produce up to four liters of drinking water a day — enough to quench the thirst of a typical person.

In a paper published this week in the journal PLoS ONE, the researchers demonstrate that a small ...

Study finds social-media messages grow terser during major events

2014-02-27

In the last year or two, you may have had some moments — during elections, sporting events, or weather incidents — when you found yourself sending out a flurry of messages on social media sites such as Twitter.

You are not alone, of course: Such events generate a huge volume of social-media activity. Now a new study published by researchers in MIT's Senseable City Lab shows that social-media messages grow shorter as the volume of activity rises at these particular times.

"This helps us better understand what is going on — the way we respond to things becomes faster ...

Humans have a poor memory for sound

2014-02-27

Remember that sound bite you heard on the radio this morning? The grocery items your spouse asked you to pick up? Chances are, you won't.

Researchers at the University of Iowa have found that when it comes to memory, we don't remember things we hear nearly as well as things we see or touch.

"As it turns out, there is merit to the Chinese proverb 'I hear, and I forget; I see, and I remember," says lead author of the study and UI graduate student, James Bigelow.

"We tend to think that the parts of our brain wired for memory are integrated. But our findings indicate ...

DNA test better than standard screens in identifying fetal chromosome abnormalities

2014-02-27

BOSTON (Feb. 27) – A study in this week's New England Journal of Medicine potentially has significant implications for prenatal testing for major fetal chromosome abnormalities. The study found that in a head-to-head comparison of noninvasive prenatal testing using cell free DNA (cfDNA) to standard screening methods, cfDNA testing (verifi® prenatal test, Illumina, Inc.) significantly reduced the rate of false positive results and had significantly higher positive predictive values for the detection of fetal trisomies 21 and 18.

A team of scientists, led by Diana W. Bianchi, ...

More evidence that vision test on sidelines may help diagnose concussion

2014-02-26

PHILADELPHIA – A simple vision test performed on the sidelines may help determine whether athletes have suffered a concussion, according to a study released today that will be presented at the American Academy of Neurology's 66th Annual Meeting in Philadelphia, April 26 to May 3, 2014.

The study provides more evidence that the King-Devick test, a one-minute test where athletes read single-digit numbers on index cards, can be used in addition to other tests to increase the accuracy in diagnosing concussion.

For the study, 217 members of the University of Florida men's ...

IU study ties father's age to higher rates of psychiatric, academic problems in kids

2014-02-26

BLOOMINGTON, Ind. -- An Indiana University study in collaboration with medical researchers from Karolinska Institute in Stockholm has found that advancing paternal age at childbearing can lead to higher rates of psychiatric and academic problems in offspring than previously estimated.

Examining an immense data set -- everyone born in Sweden from 1973 until 2001 -- the researchers documented a compelling association between advancing paternal age at childbearing and numerous psychiatric disorders and educational problems in their children, including autism, ADHD, bipolar ...

Improved prescribing and reimbursement practices in China

2014-02-26

Bethesda, MD — Pay-for-performance—reimbursing health care providers based on the results they achieved with their patients as a way to improve quality and efficiency—has become a major component of health reforms in the United States, the United Kingdom, and other affluent countries. Although the approach has also become popular in the developing world, there has been little evaluation of its impact. A new study, being released today as a Web First by Health Affairs, examines the effects of pay-for-performance, combined with capitation, in China's largely rural Ningxia ...

3-D microgels 'on-demand' offer new potential for cell research

2014-02-26

Stars, diamonds, circles.

Rather than your average bowl of Lucky Charms, these are three-dimensional cell cultures generated by an exciting new digital microfluidics platform, the results of which have been published in Nature Communications this week by researchers at the University of Toronto. The tool, which can be used to study cells in cost-efficient, three-dimensional microgels, may hold the key to personalized medicine applications in the future.

"We already know that the microenvironment can greatly influence cell fate," says Irwin A. Eydelnant, recent doctoral ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

A comprehensive review charts how psychiatry could finally diagnose what it actually treats

Thousands of genetic variants shape epilepsy risk, and most remain hidden

First comprehensive sex-specific atlas of GLP-1 in the mouse brain reveals why blockbuster weight-loss drugs may work differently in females and males

When rats run, their gut bacteria rewrite the chemical conversation with the brain

Movies reconstructed from mouse brain activity

Subglacial weathering may have slowed Earth's escape from snowball Earth

Simple test could transform time to endometriosis diagnosis

Why ‘being squeezed’ helps breast cancer cells to thrive

Mpox immune test validated during Rwandan outbreak

Scientists pinpoint protein shapes that track Alzheimer’s progression

Researchers achieve efficient bicarbonate-mediated integrated capture and electrolysis of carbon dioxide

Study reveals ancient needles and awls served many purposes

Key protein SYFO2 enables 'self-fertilization’ of leguminous plants

AI tool streamlines drug synthesis

Turning orchard waste into climate solutions: A simple method boosts biochar carbon storage

New ACP papers say health care must be more accessible and inclusive for patients and physicians with disabilities

Moisture powered materials could make cleaning CO₂ from air more efficient

Scientists identify the gatekeeper of retinal progenitor cell identity

American Indian and Alaska native peoples experience higher rates of fatal police violence in and around reservations

Research alert: Long-read genome sequencing uncovers new autism gene variants

Genetic mapping of Baltic Sea herring important for sustainable fishing

In the ocean’s marine ‘snow,’ a scientist seeks clues to future climate

Understanding how “marine snow” acts as a carbon sink

In search of the room temperature superconductor: international team formulates research agenda

Index provides flu risk for each state

Altered brain networks in newborns with congenital heart disease

Can people distinguish between AI-generated and human speech?

New robotic microfluidic platform brings ai to lipid nanoparticle design

COSMOS trial results show daily multivitamin use may slow biological aging

Immune cells play key role in regulating eye pressure linked to glaucoma

[Press-News.org] Impact on mummy skull suggests murderAnalysis of archived mummy reveals murdered young female with Chagas disease